by Rob Callahan

In a nondescript Burbank falafel joint on a sweltering Sunday afternoon in July of last year, co-workers crowded around an impromptu conference table made up of several four-tops pushed together. A tacky film adhered to the furniture, as is typical of greasy spoons. Sweaty forearms clung stickily to gummy tabletops.

DTDC employees wore ‘Contract Now’ T-shirts to work in a show of solidarity, and posed in the shirts for photos to post on social media.

Folks hadn’t shown up for the ambiance, or the tabbouleh. They’d come for one another, and to do something they couldn’t inside their workplace. After months of hushed, one-on-one conversations and small, covert huddles, they’d gathered to speak openly and frankly amongst themselves about their frustrations with their employer.

These employees worked at the nexus of two trends that define the 21st-century economy: information technology and globalization. Their jobs were to create the digital cinema packages (DCP) distributed worldwide for the exhibition of theatrical features. Their employer, Deluxe Technicolor Digital Cinema (DTDC), is overwhelmingly the dominant player in this arena, handling the bulk of releases from major studios and independent distributors.

The group skewed young — 20s or early 30s. Their work wasn’t celebrated; their names didn’t appear in the end-crawls of the movies on which they’d worked. The labors of these young workers, though, put entertainment on screens around the world. Without their efforts, innumerable kernels of popcorn would remain unpopped.

The function such workers now perform used to be performed by technicians who made physical reels of actual film, rather than virtual packages of files. DTDC fills the space once occupied by Hollywood’s two storied film laboratories, Technicolor and Deluxe. Those film labs had provided solidly middle-class union jobs for generations of technicians. Hundreds of our Guild brothers and sisters (the lab technicians local merged with Local 700 in 2010) lost their jobs when the industry’s transition to digital theatrical projection led to the downsizing and eventual closures of the film labs.

A common article of faith amongst economists is the belief that, although the industrial disruption effected by technological innovation may eliminate jobs in the short term, it ultimately creates new and often superior opportunities for employment. Our economy no longer has much demand for telephone operators, but it now affords plenty of opportunities for mobile app developers. Shiny new jobs, say proponents of technology’s disruptive effects, spring up to replace dusty positions rendered obsolete.

I can’t vouch for how things work on the macro-economic scale, or whether faith in the ultimate beneficence of technological disruption is warranted. I can say that new jobs for digital cinema technicians were indeed created to replace the film labs’ lost jobs, but these new jobs were both much fewer and much less well-compensated than the jobs they supplanted.

Employees of Deluxe Technicolor Digital Cinema during their half-day strike on February 2, 2017. Photo by Deverill Weekes

The digital cinema technicians gathered in Burbank last summer came from a group of about 70 such folks employed at Deluxe Technicolor Digital Cinema; each of the film labs had employed hundreds in analogous positions prior. Moreover, the DTDC employees shared stories of low wages, of having gone years without cost-of-living increases, and of substandard health and retirement benefits.

Without these technicians’ efforts, the studios would have literally nothing to show for all the enormous investments of resources and talent they put into the production of feature films. Yet the people performing this final stage of post-production work consistently complained of stagnant wages, and many spoke of difficulties paying rent and other basic expenses. “After years of little or no pay increases, a large majority of us were living paycheck to paycheck, some just scraping by,” said Jackson Benjamin, a quality control operator at DTDC.

It wasn’t all about compensation for them, though. It was also about dignity. Many of them volunteered stories of a corporate culture that left them feeling disrespected, even disposable. “We collectively felt that the company was not taking us, or our requests, seriously,” said Moshe-Aaron Lopez, a mastering technician. “This was never about just scoring a win; it was always about what was right. We organized because it was the right thing to do.”

It wasn’t all about compensation; it was also about dignity. “We organized because it was the right thing to do.”

For decades now, enemies of organized labor (and even some of labor’s half-hearted, liberal “friends”) have encouraged the public to regard unions as anachronisms, relics of an industrial past with little relevance for the country’s post-industrial future. We must admit that there’s real cause for pessimism about the prospects for organized labor. Sixty years of dramatic decline have reduced the rate of union membership to a fraction of what it once was. Technological developments and sea changes in the global economy have resulted in the elimination of many of the US manufacturing jobs that constituted the bedrock of the American labor movement in its heyday. As the demise of the film labs reminds us, such market forces have taken a heavy toll close to home.

Yes, labor has taken and continues to take a beating. But many go further to claim that unions have lost their raison d’être. Collective bargaining, they say, is intrinsically ill-suited to the employment of the emergent new economy: service sector, high-tech, professional, creative and casual jobs that don’t lend themselves to the framework of shop floor democracy. Perhaps unions made sense in the context of coal mines, steel mills or automobile factories, our detractors assert, but they’ve no more role to play in the information age than do typewriters or celluloid.

Those cheerleading for unions’ obsolescence characterize the trends that have sapped organized labor of its strength as forces of nature — like gravity or magnetism — immutable laws beyond the influence of individual or collective human action. They hold that the decline and eventual extinction of organized labor is inevitable, irreversible and intrinsic to the essential workings of the marketplace. To resist the trend, they would have us believe, is not merely to tilt against windmills, but to fight the invulnerable tide.

In fact, it’s neither natural nor even accidental that newly created jobs are non-union. It’s a deliberate choice that employers make, and they put real effort and resources into ensuring that those positions remain non-union.

The DTDC employees at that lunch decided that they’d do better through collective bargaining. Too many of them had already been rebuffed after having individually approached supervisors seeking raises or other improvements on the job. If they wanted to make changes in the workplace, they needed to forge a unified front and all approach management together. Folks left the meeting committed to reaching out to more co-workers, and bringing more on board with the idea. Before long, an overwhelming majority of DTDC’s digital cinema technicians had pledged support for the effort.

Management eventually got wind that employees were talking union, and they determined to fight the movement. Starting in late August, they instructed employees to attend a series of on-the-clock meetings in which managers exhorted them not to organize. Deluxe’s CEO even showed up to conduct meetings himself. These town hall meetings were supplemented by one-on-one interviews in which individual bosses spoke to individual employees alone, without witnesses.

Employees were told not to trust promises from union organizers. They were told that organizing would introduce a third party that would get in the way of a direct and healthy relationship between management and employees. They were told that union negotiations could drag on interminably, but that management could make improvements on the job right away if employees voted not to unionize. They were told that contract negotiations could actually leave them with less than they already had.

Such pressure tactics from management are the norm in organizing drives. Often, these “union avoidance campaigns,” as they’re euphemistically described by union-busting attorneys and consultants, work. Bosses’ constant haranguing can introduce enough doubt or anxiety that workers abandon their organizing aspirations, opting instead to stick with the status quo.

The law bars employers from using explicit threats or bribes to discourage employees from organizing. Employers will step right up to that legal line, however, and sometimes over it. In one-on-one meetings, in which improper conduct is tricky to prove, management can speak even more freely about potential rewards for loyalty or punishment for disobedience.

Even if bosses scrupulously avoid explicit threats or promises, management-run anti-union campaigns are intrinsically coercive. Having your boss repeatedly admonishing you how to make up your mind is an infringement upon your free choice, whether or not there’s mention of consequences for failing to heed that advice.

Management’s strong-arm tactics often succeed, but not always. Fortunately, employees who have built strong bonds and who have committed rank-and-file leaders can weather a campaign of anti-union bullying and naysaying. Despite Deluxe having spent several weeks pressuring DTDC employees to reject the organizing effort, in the fall of last year they voted by a margin of more than two-to-one to unionize with the IATSE and Editors Guild. It was a huge victory, and a dramatic rejection of management’s pressure campaign.

“Management tried very hard to discourage our union organizing,” said Lopez, “I’m extremely proud of all my co-workers for standing in unity and believing in themselves.”

Winning union recognition guarantees a group of employees a voice on the job. Employees must then use that voice to demand and secure a fair union contract.

Winning union recognition guarantees a group of employees a voice on the job. But to make material improvements in working conditions, employees must then use that voice to demand and secure a fair union contract.

Negotiations for an initial union contract at a fixed facility are seldom speedy, in part because they require a lot of preparation on the union’s part. Employees need to be surveyed and have an opportunity to weigh in on collective priorities. A bargaining committee needs to be assembled to represent their coworkers at the negotiating table. Contract proposals need to be drafted.

DTDC employee Moshe-Aaron Lopez on the picket line. Photo by Deverill Weekes

Even after the overwhelming vote in favor of unionizing, DTDC employees had to continue pressuring management to come to the table and negotiate in good faith to reach a fair agreement.

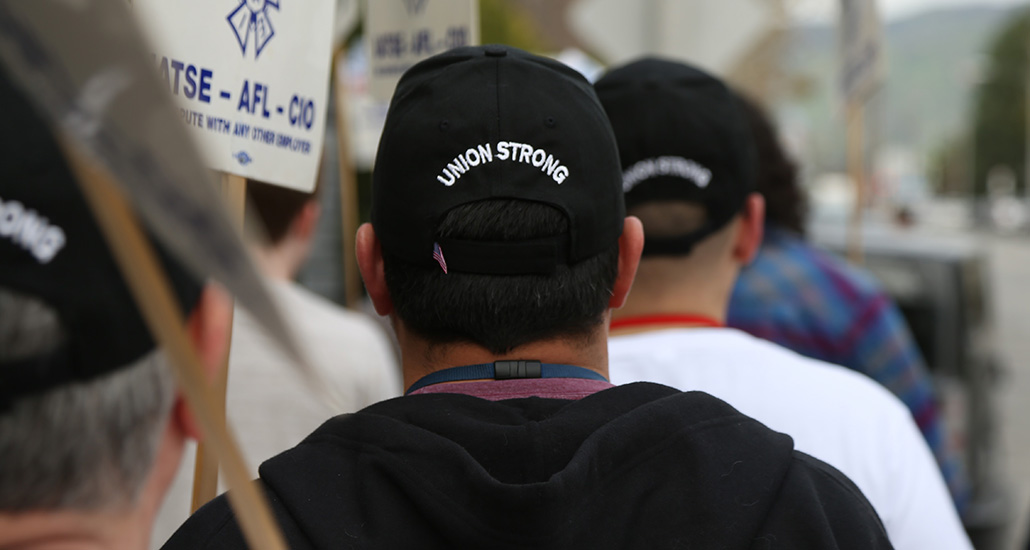

Over the course of several months, employees attended mass meetings; wore union buttons, “Contract Now!” T-shirts and “Union Strong” baseball caps to work; marched into the boss’ office to deliver a petition urging movement on key issues; and even took part in a brief, half-day work stoppage to protest management’s failure to negotiate in good faith. The company hadn’t wanted these jobs to be union, and it took continuous pressure to get them to come to, and then move at, the bargaining table.

But all of that pressure paid off. The negotiating team reached a tentative agreement in May of this year, and in June, DTDC employees voted overwhelmingly to ratify their first union agreement.

The contract now provides them with Motion Picture Industry Pension and Health benefits; employees’ annual savings in premiums alone will range from about $1,500 to about $15,000. They also won a wage schedule that will ensure much-improved pay. The deal provided immediate and retroactive raises, ranging up to 30 percent. Most workers will see raises ranging from 21 to 38 percent over the three-year life of the contract.

Most workers will see raises ranging from 21 to 38 percent over the life of the contract.

The contract doesn’t solve DTDC employees’ every concern, though. There will be more to fight for in future negotiations. These digital cinema technician jobs are still not as highly compensated as the traditional cinetechnician jobs they replaced, and we can’t bring those old jobs back. But, because of the courage and cohesion that these employees demonstrated, we were able to ensure that the folks performing this new work have a voice on the job.

“This agreement will improve the quality of life for myself, my co-workers and their families. By coming together to have a more powerful voice, we established a mutual respect between technicians and management,” Benjamin said. “To have and express conviction for what is right — that truly earns respect. Not just from management, but simply self-respect, too. This is essential in every workplace.”