by Bill Desowitz

It was bound to happen, eventually, that Steven Spielberg would finally embrace the Avid. His longtime collaborator and editor Michael Kahn, A.C.E., finally wore down the director’s resistance to going digital in post-production. It just took the right movie at the right time. Instead of the usual case of technology catching up with need, it was the other way around. When Spielberg decided to take the plunge and direct his first animated feature, The Adventures of Tintin — in theatres December 21 through Paramount Pictures and Columbia Pictures — the performance-captured virtual production necessitated a complete digital workflow, so it only made sense that Kahn would convince him that the film should be cut digitally.

Apparently, Spielberg is now a convert to the digital domain, as they used the Avid on their two subsequent live-action movies shot on film, War Horse, which Disney opens Christmas Day, and Lincoln, due from Touchstone in 2012. The speed and efficiency have become contagious for the director.

“Starting with Tintin, where there is no film step, Michael introduced me to the Avid,” Spielberg said in an e-mail for this article. “Because some of our creative work was going to overlap on War Horse, he persuaded me to let him edit that digitally, too. The one pledge we have made to each other is that we will never allow the convenience and the speed of the Avid to ever accelerate our process. We will cut digitally but we will think analogue.”

A scene from The Adventures of Tintin.

Photo: WETA Digital Ltd./Paramount Pictures

The KEMs and Moviolas will still be around if Spielberg gets the itch to use them again. Of course, Kahn had already learned to cut digitally when working with other directors, but sympathizes with Spielberg’s need to keep one foot in analogue. Kahn says that’s because the director loves the taste of film — he likes to take the time to ruminate about a scene while walking for an hour or talking on the phone or reading. For his part, Kahn won’t be rushed into choosing from a digital buffet, but he’s learned to work faster in the cutting room than Spielberg.

Fortunately, it was a comfortable transition with Tintin, their first foray into 3-D as well as computer animation. The action-adventure is adapted from the popular Belgian comic books by Hergé about a globetrotting teenage reporter in the 1930s with his trusty terrier and drunken sidekick. New technology aside, they still cut it together after agreeing on the order of scenes and choices of takes.

“Like every other film, we discuss it and Steven selects his takes and asks me to put it together; then he makes adjustments,” Kahn elaborates by phone from Virginia, where they’re shooting Lincoln, their 25th film together. “But it goes very fast on the Avid. We didn’t know much about performance capture, but it was like a new experience, so I talked to a number of people who have done this and it’s supposed to be complicated and very, very difficult. But I can tell my fellow editors that they shouldn’t be afraid of this thing; it’s just like regular editing. No difference at all because he’d go out and shoot, and I’d get the dailies the next day.”

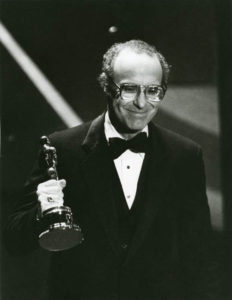

Michael Kahn won his first Oscar for Best Picture Editing for Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). Photo: AMPAS

However, Spielberg shot Tintin just like live action on a motion-capture stage in Los Angeles with a modified virtual camera/controller. This allowed him to work very quickly during the span of a month in 2009, getting up to 75 setups a day in sequence and in real-time. They also started to cut the movie much earlier. But in spite of the brave new digital world, it still all comes down to the basics of storytelling — which means that the two filmmakers really haven’t altered the way they collaborate.

Kahn was not impacted at all by the 3D, which was rendered as part of the final process. “The amazing thing is that when you get the dailies and they’re rendered, you get the characters in their environments in the right place,” he enthuses. “Of course, the mouths didn’t work; the characteristics of the face didn’t work. That was done later at WETA [in New Zealand]. But to get the diversity of backgrounds and sets is [fantastic].”

Although Kahn is very humble about his creative contribution, deferring always to his director, he acknowledges the fun of having Tintin move along so breathlessly, recalling the Indiana Jones, Hitchcock and Bond movies. One of the highlights is a bravura motorcycle chase up and down the hilly landscape of Morocco lasting several minutes — all in one take.

“Steven was energized and so was I,” Kahn recalls. “It’s like going back to square one when you have all your options open. In fact, you have more options than before. You can go back into the volume and change the expression, the reactions. Whatever you need, you get it right away. Every time we got new dailies, my assistants and I were in shock the way it was put together.”

For Kahn, it has been just as comfortable continuing to work on the Avid on War Horse and Lincoln. “There were no trims to choose from; you just push a button,” he laughs. And it wasn’t even confusing for him going back and forth between Tintin and War Horse, although it was unusual in that they were still tweaking the former long after the latter was completed.

Kahn says that whenever he starts a new film, he gets rid of all the old baggage, thanks to an inspirational book about Buddhism: Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. “It’s like the first time I’m doing it, so there’s a lot of excitement and there’s no exhaustion, no tiredness from the previous show, even if there’s an overlap,” he says. “It’s how you handle that footage, too. Steven has said many, many times that he shoots for the editing room so he’ll have options later. They spend a lot of time fixing scripts before they even shoot it, so it’s what we do with it that makes it count.”

War Horse, of course, is the proverbial equine of a different color. Based on the young adult novel by Michael Morpurgo, as well as the popular London stage play, it’s a sweeping World War I saga told from the point of view of a horse named Joey separated from his pal, Albert (Jeremy Irvine), and the odyssey they endure to reunite.

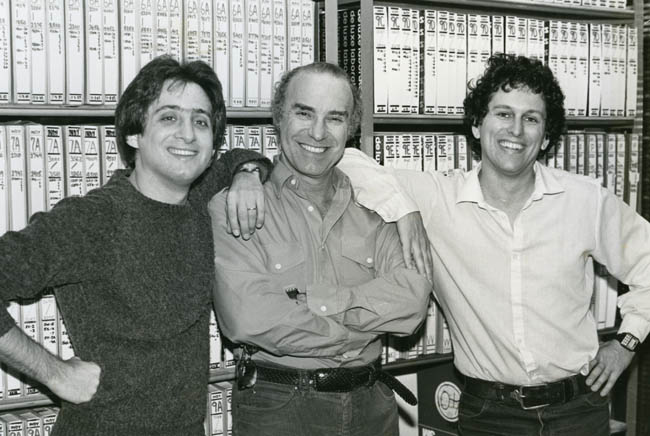

Michael Kahn flanked by assistant editors Steve Kemper, left, and Bruce Green during the making of Indiana Jones & the Temple of Doom (1984). Photo: MPEG

Kahn considers the film right up there with their best. “I love it and I think people are going to love it; there’s emotion that people can relate to,” he says. “Just working on it was incredibly moving. It took me back to basics, back to love among animals and human beings. It just lifts you up and you feel good about this horse that goes through a lot to survive.”

Spielberg and Kahn have survived a lot together too since their first encounter on Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). “With Steve, it’s similar to what I like to do,” Kahn reveals. “He does things intuitively and has a good feeling for things. He feels it when it’s right and I like to feel it when it’s right. I’ve used this phrase before: Rather than working from knowledge, you work from feeling, you work from intuition. And on War Horse, Steve gave us a lot of choices in the editing room to go with the feeling. I think the theme of love is really what it’s about in spite of the problems that the horse and the boy had.”

There’s a lyrical, majestic beauty to the film, and it’s a movie filled with striking contrasts both thematically and visually. It traverses the beautiful and peaceful countryside as well as the dark and explosive front lines of both sides. Yet Albert and Joey remain indefatigable.

“The picture starts off — and we don’t rush it; we just go along with the feeling of the farmers there, the people that own the horses and what they do,” explains the editor. “And then, as the show goes on, it starts going up and up and up like a stock market and really hits a pinnacle at the end of the show. You’re doing it in a pastoral way, a comfortable way, and you’ve gotta be more aggressive, filmically, and you just feel like tearing up sometimes. My assistants and I like to watch it, and we never tire of looking at it. Steven brings a quiet power to these pictures.”

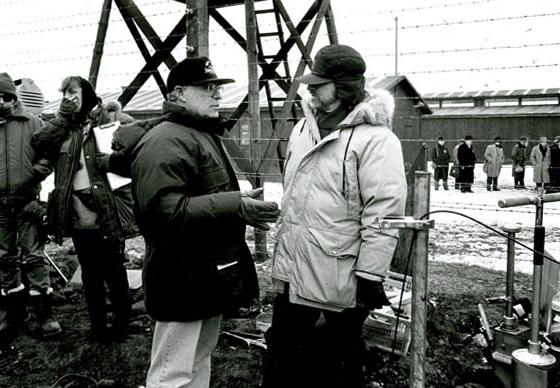

Michael Kahn, left, and Steven Spielberg on the set of Schindler’s List (1993).

Photo: DreamWorks Archives

Ask Kahn what his favorite of his films is and he says it’s impossible to choose one. But he immediately ticks off Close Encounters as a touchstone. He prefers the original theatrical cut, though, and, again says that you know when it feels right. “I keep hitting that ‘feel’ thing because that’s what we talk about, and we make the adjustments. Everything we’ve done is that way, whether it’s action or emotion — or Schindler’s List [1993].”

Speaking of Schindler’s List, Kahn acknowledges that the film, which won him his second Oscar, reached new dramatic heights, and that he and Spielberg were both emotionally ready for the Holocaust crucible. But being on location was extremely difficult. “All I can tell you is that when I came home after Schindler’s List, I was in shock,” admits Kahn. “We were in Poland and I crossed the bridge where all the Jews crossed. I looked down and said, ‘Oh, my God! This is the place!’ And then we’d go down to the camps and see where all that havoc went on, and it brought me down. It just took a lot out of me because it was so emotionally real. There was nothing phony about it.

“I remember we ran the film for the Academy and afterward people sat there in silence,” he continues. “I never saw anybody do that after a screening before. And it was just so gratifying, the emotions it brought forth. Steven was so right.”

Kahn also singles out another World War II film, Saving Private Ryan(1998), his third Oscar winner. “I loved the action and the story, and they shot with different cameras for the opening,” Kahn says. “Steven and I would go through it and he said, ‘Why don’t you try that?’ They had three or four different styles. Sometimes they shot 12 frames a second and we had to bring it up to 24 — that would give us a real look of the way the war used to look [on film]. It was very, very effective.

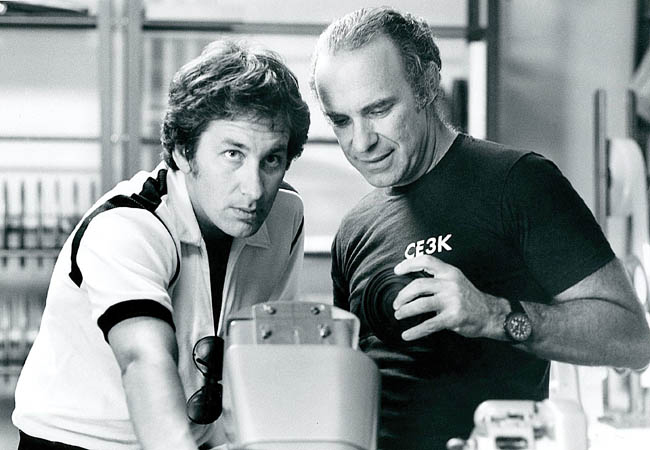

Steven Spielberg and Michael Kahn working in the early 1980s. Photo: DreamWorks Archives

“When we got back to England, we started shooting on this airfield,” he continues. “Every day, Steven would come in and look at the opening, and I’d say, ‘How come you’re looking at this?’ And he’d say, ‘I don’t want the ending to be too similar to the opening.’ And that’s what happened — he shot a wonderful ending and it wasn’t too similar to the opening.”

But Kahn really enjoys tackling every genre, from Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), for which he earned his first Oscar, to The Color Purple(1985) to Jurassic Park (1993) to Munich (2005). “That’s what’s great — Steven shoots different genres and doesn’t stay the same,” he says. “That makes it wonderful and I feel comfortable doing all of them. There is no genre I haven’t done.”

The editor then adds: “When we got to this animated film, he said, ‘We’re doing Tintin.’ I said, ‘You mean, Rin Tin Tin?’ ‘No, Tintin, the Belgian comic.’ I’d never heard of it and neither had any of my crew. But I think technologically it’s a wonderful lesson in how these things are done. It was just a different experience for us.”

It’s always a different experience for Kahn, including with Lincoln, starring Daniel Day-Lewis as the beloved 16th US President. Spielberg describes it as a procedural that focuses on the crucial last four months of Abraham Lincoln’s life when he guided the North to victory in the Civil War and plotted to end slavery once and for all with the hard-fought passage of the 13th amendment.

A scene from War Horse. Photo: DreamWorks II Distributiond

Kahn promises that we’re going to see Lincoln as never before — the devoted husband and father and shrewd politician, maneuvering with godspeed to repair the nation, correct a moral flaw and secure a legacy before time runs out. “You won’t even know it’s an actor; you’ll think it’s Lincoln,” Kahn insists. “It’s well-known that he was a great storyteller, and he used that to his advantage. And you really like him.

But he had to do some terrible things,” Kahn continues. “During war, it’s hard to be a commander-in-chief. But I learned things about Lincoln that I didn’t know from school. He kept the union together, he opposed slavery, but it’s how he did it — how he handled people. You have the opportunity to see how he felt, what was inside of him. He had a lot of doubts and fears, but he was able to handle it.”

Throughout the years, Kahn says that he’s learned so much historically and emotionally by working with Spielberg. “You know, I’m so blessed that Steven chose me years ago because we’ve gotten along well; it’s been wonderful and we share everything here in the editing room,” he concludes. “I’ve grown a lot with him; I’ve matured and he’s matured. I feel we’re like brothers. I love the guy and it’s been a wonderful trip. There are a lot of things you learn as an editor, if you keep your head up.”

For his part, Spielberg returns the compliment, again, via e-mail: “We know how talented Mike is and working exclusively together now going on 36 years, he is the brother I never had. We finish each other’s sentences and we finish each other’s sequences. I cannot imagine directing a picture without him nudging me to get more coverage.”