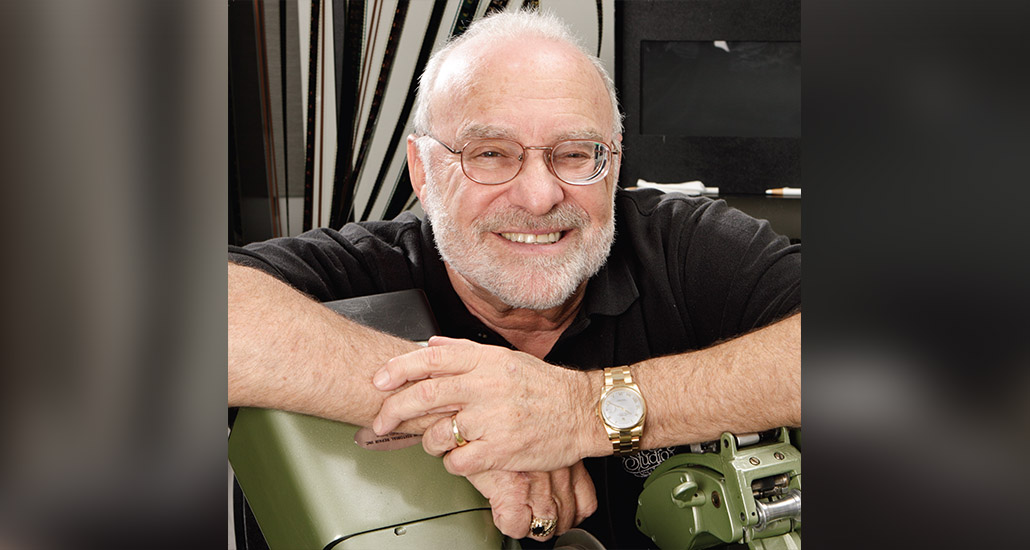

by Michael Kunkes • portraits by Gregory Schwartz

This year, film editor Michael Kahn, ACE, will mark his 30th anniversary with director Steven Spielberg, a run of success equaled only by the director-editor teaming of Clint Eastwood and Joel Cox, ACE, and Martin Scorsese and Thelma Schoonmaker, ACE. Though he has worked with other directors––most notably Adrian Lyne on Fatal Attraction (1987)––it is Spielberg with whom his name is most linked, beginning with Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and continuing through such diverse content as The Color Purple (1985), Jurassic Park (1993), Catch Me If You Can (2002) and three Indiana Jones movies. The collaboration has yielded three Best Editor Oscars for Kahn (Saving Private Ryan, 1998; Schindler’s List, 1993; and Raiders of the Lost Ark, 1981), in addition to three American Cinema Editors Eddies, two BAFTAs, and an Emmy (Eleanor and Franklin, 1976).

His 20th film with Spielberg, Munich, opens December 23 through Universal Pictures. Munich tells the story of a secret team of Israel’s Mossad agents sent out on a mission in the aftermath of the hostage-taking and murder of 11 Israeli athletes by the Black September terrorists at the 1972 Munich Olympic games. It is by turns a thriller and a reflection on the personal toll that vengeance takes on its participants. CineMontage spoke with Kahn (who granted a rare interview), in his editing bay in the Howard Hawks building at 20th Century Fox, about the film, and his 30-year working relationship with Spielberg.

CineMontage: How did you get your start in editing?

Michael Kahn: I was working for a large ad agency in New York, and they brought me out to the coast to produce some commercials. I ended up being offered a secretarial position in the editorial office at Desilu. Dann Cahn, who was editing I Love Lucy, got me into the union, and the first show I worked on was 1956’s The Adventures of Jim Bowie, where I worked with John Woodcock. The man who really made me an editor was a terrific guy named Danny Nathan, whom I assisted at Bing Crosby’s company. He gave me a big scene to cut and when I showed it to him, he said, “Oh my god!”

Michael Khan

CM: ‘Oh my god’ good, or ‘Oh my god’ bad?

MK: Bad! I kept going back and making changes and when we ran it for the executives at Crosby, they said, “Danny, you did such a great job on that convention scene.” But he was a mensch and said, “The guy who cut that scene was my assistant, Mike Kahn.” Because of that nice plug, I got a job assisting on Hogan’s

Heroes and, after four shows, I became the series’ regular editor from 1965-1971.

CM: How did the television experience help your understanding of the craft?

MK: I was the kind of kid who would do anything, and of course, television was where you really learned how to cut. It was really difficult in terms of making decisions and at first, I didn’t really know what I was doing, but I started to realize that I could maneuver the film to do what I wanted, to change the mood and the feelings. I learned that once you have control of the film and feel confident enough, you can do anything you want to do.

CM: What editors did you admire the most?

MK: The two editors I thought were the greatest were Ralph Winters [Ben-Hur, 1959; A Shot in the Dark, 1964], who passed away in 2004, and the late William Reynolds [The Sound of Music, 1963; The Godfather, 1972]. I was once on a panel with Ralph where he said that when we cut film in those days, a lot of times we

just cut the slates off, because there was not much coverage. Today, of course, editing has a much more prominent position, because more coverage allows more editing choices after production shooting. A film isn’t going anyplace until its boundaries and values are established in the cutting room.

CM: How did you begin your collaboration with Steven Spielberg?

MK: Steven was looking for an editor to work with on Close Encounters of the Third Kind. He interviewed everyone in town and finally he came to me. In 1976, I had just finished cutting Return of a Man Called Horse, and was recommended by both Irvin Kershner, who directed that show, and the film’s cinematographer, Owen Roizman, who was a good friend of Steven’s. When I met with Steven, he asked me if I was a good editor. I said, “How can I tell you that? All I know is that whoever I work with wants me back again.” The next thing I knew I was hired.

“We had to work that rapidly, and we did. Steven Spielberg would shoot on Monday, we’d run dailies on Tuesday, and I’d show him a cut scene on Wednesday.” – Michael Khan

CM: Why has your relationship with him been so successful?

MK: Because I have a natural desire to see how the film is going to turn out, I work very intensely. There is an intensity in me that simply cannot stand to see film sitting on the shelf, waiting to be styled and morphed into something interesting. Steven has exactly the same attitude. He is very obsessive with a film and can’t wait to see it completed. Our personalities really match quite well.

CM: Can you describe how your working relationship has evolved? How does a typical show with Steven proceed?

MK: Right from Close Encounters, we started a routine that continues to this day. First of all, I almost never look at dailies in the projection room, and Steven hardly does either. I run dailies with him on a KEM; he selects the performances he likes and gives me his ideas about how a scene should go. Then I’ll put it together

and show it to him. It’s all pretty structured when I sit down with him, because my feeling is: Why edit something if he’s going to change the performances later anyway?

So I cut as scenes come in. Steven sees the edited scenes the next day, and any adjustments are made. I do each sequence and put my own leader on it; then when I’m done, I line them all up in order. When I’m all through and Steven sees everything, we mount the show. Without that structure, it’s a waste of time, to say nothing of matching and all. After all these years, I get fairly close on my first cut so that normally, by the time he’s looked at it once or twice, we’re real close.

CM: Are you always in agreement?

MK: There’s never an adversarial relationship. Steven always says to me, “You have your takes, cut it the way you feel it and I’ll see if I like it.” The only choice you give a director is when you challenge him and cut a scene differently than what he expects. If he doesn’t like it, he at least has the opportunity to see it that way and say no. Sometimes, I’ll say to him, “Steve, I’m not sure how to put this sequence together and I need a little input from you.” He loves that because I am being honest, and a little honesty goes a long way. No one makes the perfect picture, at least not on the first cut. Ego must never be involved. It’s always the director’s film and editors should not have a sense of ownership––though sometimes they do.

“There’s no doubt that the director and the editor, working in concert, control the film. The coverage he gives you and the level of collaboration that you as an editor bring to the table is what’s going to make the film.” – Michael Khan

CM: Dede Allen says, “You cut with your gut.” Would you agree with that?

MK: I think she’s right. Editing is not a mechanical process. Whether you are cutting on a Moviola or an Avid, it’s all up here [points to head] and in here [points to heart]. All editors can cut; the only difference is their personality and the desire to make the best film they can.

CM: Do you feel you are still growing creatively?

MK: Without a doubt. Age has nothing to do with this. Growth is a process of acceptance and being open to new ideas and new challenges. Every time I go onto a new picture I am into a new existence; a new world.

CM: Let’s talk about the post on Munich; what was the process?

MK: Going in, we knew it was going to be a tough schedule. We started shooting in late June and we knew we needed to deliver an answer print by the end of November. Because of the short schedule, we set up a methodology that was different from anything I’d done before. I needed to work extremely rapidly, so I put my first assistant, Pat Crane, completely in charge of the editing room. He would have to run everything, handle all the day-to-day phone calls, get me all my materials and take care of the politics. He did all that and more.

CM: So you were cutting the show all during the shoot?

MK: Yes. We spent six weeks in Malta, then six weeks in Budapest. From there we went to Paris––all at different locations. For each location, Pat found and rigged up an old truck in which we had our Moviola and a KEM. One of them was an old freezer truck, the other was a big box truck that he cut a couple of windows in and added air conditioning to. We’d park next to Steven’s trailer on the set so that he could come and see us in between shots. He also had a KEM set up in whatever apartment or hotel suite he was living in so we could work there as well. The great thing about this was that Steven gave me access anytime day or night, and this was the first time that’s ever happened this fast. His focus was amazing, in that he was able to simultaneously direct, then edit with me. Steven’s just an amazing guy. I’d edit a scene, then run right out to the set to let his people know we were there. He’d pop in, make some changes, then go back to the set. We were completing scenes at a rapid pace; it was the only way we could get this done in time.

“I like film because, as an editor, you are forced to have a point of view and to make decisions that can only go one way at a time. This is unlike electronic editing, where you bring several versions to the director and he takes some from column A and some from column B to put a film together. That’s not making editors’ decisions.” – Michael Khan

CM: How were you able to maintain such an accelerated pace?

MK: We had to turn over scenes as early as July for John Williams, the composer, and Ben Burtt, the supervising sound editor, so they could start thinking about the music and sound effects. Fortunately, Steven is such a quick study that if something bothered him or if there was something we could do better, I was able to make those changes immediately because of the access I had to him. As an editor, you can only imagine what this was like. We’re finishing scenes; the show’s not even mounted yet and we don’t know what’s going to stay in or get taken out.

But we had to work that rapidly, and we did. Steven would shoot on Monday, we’d run dailies on Tuesday, and I’d show him a cut scene on Wednesday, where on a regular picture I’d see him once or twice a week. I’ve never been so focused or worked any faster. It was actually fun and challenging; we were cooking. Steven is

very focused and he wants everyone around him to be focused.

CM: Spielberg is known for shooting a lot of film. How were you able to keep up with the flow of dailies?

MK: There was never much of a lull. During the week of shooting in Paris, I decided that I wasn’t going to edit and just be on the set with him for a week, during which we finished running everything that was left from Budapest and Malta. The production then went to New York to shoot for a week and I went home and cut at Fox, so that by the time he came back to Los Angeles, all that was left to cut was that week in New York. We did that and we had our show.

CM: Munich alternates several big action scenes with a lot of more reflective moments. Are there times when not cutting is just as effective as cutting?

MK: The rhythms were very varied, yes, but we haven’t done a picture like this before. Where something important was being said, Steven let it play; for example in the scene where Avner and Ephraim take a long walk down the esplanade and just talk. You know, sometimes when you don’t cut, you can hear the dialogue better [laughs]. This was also a great picture to work on because it allowed Steven and I to do a lot of montage sequences, such as the first meal scene where the team is getting to know each other, we used a lot of MOS [without sound] shots where people were just looking at each other.

In my 30 years of working with Steven, this was the show where the editing technique was different from any other picture. When Steven has his team together, it functions like a family––people like composer John Williams, DP Janusz Kaminsky, production designer Rick Carter and producer Kathy Kennedy. When you work together for years, and you understand each other’s working habits, everything goes much more smoothly.

“Editing was really difficult in terms of making decisions and at first, I didn’t really know what I was doing, but I started to realize that I could maneuver the film to do what I wanted.” – Michael Khan

CM: Though the movie deals with the aftermath of the Munich games, the sequence of the kidnapping and murder of the athletes plays an important role in the movie.

MK: That sequence was actually four segments––the attack at the Olympic Village, the siege at the Village, loading the hostages onto the buses and the siege at the airport. With the exception of the opening scene, those are all shown as flashbacks in Avner’s head. It was all scripted, but when Steven and I ran it, we cut the whole sequence by itself. Then we’d cut the scene that was intercut with the flashback. Then we broke it up into convenient places in the movie. The key was deciding how we were going to do it, because the scenes were all shot separately.

CM: You also did something unique with the sound in those flashbacks.

MK: We took a lot of the voices out and just let it play at a distance [especially in the airport sequence]. When we intercut the final sequence that way in Avner’s love scene with his wife, it gave the whole scene the appearance of a nightmare. Steven also wanted some of the action scenes to play without music, as in the scene where the characters are blown up; he took a lot of time setting those scenes up.

CM: What is the meaning of Munich for you?

MK: For me, peace and family was the central message. That may sound corny, but these are the themes that run through the picture. The Golda Meir character talks about family when she orders the mission; Avner and Ali, the Palestinian, talk about family in the stairway scene. Then in one of my favorite scenes––the “Poppa” scene where the Michael Lonsdale character says to Avner, “I’ll work with you, but you’re not family”––that character is like The Godfather; he’s a guy who is above it all and he’s into everything. There are those who think this is Steven’s best picture; no one can say that he doesn’t take chances––and he took a big one with this picture. It took a lot of guts, and who else could have done it?

CM: It’s well known that you still cut on a Moviola. Why is that your editing tool of choice?

MK: I’m told I might be the only guy who still edits on film. I’ve cut pictures on the Avid for other directors, such as Jan de Bont’s Twister in 1996 and Brad Silberling’s Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events last year. But Steven is a traditionalist; he likes to feel the film, see the film, touch the film. It’s no problem for me, because the work never goes any slower because of it. But I like film because, as an editor, you are forced to have a point of view and to make decisions that can only go one way at a time. This is unlike electronic editing, where you bring several versions to the director and he takes some from column A and some from column B to put a film together. That’s not making editors’ decisions. An editor should feel good about making contributions to the movie and display a point of view via his collaboration with the director.

“A film isn’t going anyplace until its boundaries and values are established in the cutting room.” – Michael Khan

CM: What do you look for in an assistant?

MK: I look for someone who is extremely sharp, who can grow and has a proper attitude. That’s a lot more important to me than knowing the mechanics of editing. Good assistants have to be able to take notes and have a grasp for everything that’s happening around them. Once they get the room down, they can move forward if they are interested.

CM: Who are some of the assistants you’ve mentored?

MK: My first assistant, Pat Crane, has been with me for 17 years [see accompanying sidebar]. I’ve also worked with Bruce Green, Billy Goldenberg, Marty Cohen and Colin Wilson, who is one of the producers of Munich. There’s a lot of them out there.

Eric Bana, center, as Avner, and Geoffrey Rush, right, as Ephraim, in a scene from Steven Spielberg’s Munich. Photo by Karen Ballard, Copyright 2005 Universal Studios and DreamWorks LLC.

CM: What’s your overall philosophy about editing?

MK: Because things can get tedious on a long shoot such as this, I always look to one of my favorite books, Shunryu Suzuki’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind for guidance. That book has always meant a lot to me, and what I get from it is to come out for every day, every scene and every sequence as if it were the first time I’ve ever edited. That way, I am completely fresh and relaxed, open to all possibilities, and the challenge is always there.

Someone once said that editing is leaving the good parts in and throwing the bad parts out [laughs]. Seriously, there is a cause and effect relationship between cuts. One cut has to lead into the next and the next and resonate back and forth so they fit.

CM: How does the director-editor relationship work for you?

MK: There’s no doubt that the director and the editor, working in concert, control the film. The coverage he gives you and the level of collaboration that you as an editor bring to the table is what’s going to make the film. An editor is only as good as his contributions to the film. All editors bring ideas and a spirit of collaboration;

what is important is how they present those ideas. An editor has to be more than just a visual typist.

CM: What’s up next for you?

MK: To tell you the truth, I don’t know. Steven and I never talk about upcoming projects because we are so zeroed in on what we are doing in the moment. That’s how deep our focus is on a show. [Future Speilberg projects that have been mentioned include the next Indiana Jones movie, an untitled Abraham Lincoln project and The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.]

CM: Any thoughts of retiring?

MK: Why? I get to work with tremendous footage, I work with the best director there is and possibly ever was. I am constantly amazed and stunned by the footage he shoots; he is so clever and smart. And I’m not here because he likes me––which he does––but because I continue to make a contribution. The irony is that I’ve been so busy that I haven’t been able to go to a movie in over a year.

CM: Any final thoughts?

MK: To all the editors in the Guild, I say, we’re in a great profession; let’s all be the best we can be.