by Peter Tonguette

For six months in the late 1970s, Steve Maslow took a trip with the Band.

No, the re-recording mixer did not go on tour with the iconic roots rock outfit, but from October 1977 to April 1978, he worked on a concert film about the Canadian group, which was then made up of its original members: bass guitarist and vocalist Rick Danko, drummer and vocalist Levon Helm, keyboardist Garth Hudson, keyboardist and vocalist Richard Manuel, and guitarist Robbie Robertson.

In The Last Waltz, released by United Artists 40 years ago in April 1978, director Martin Scorsese trained his cameras on what was intended to be the last concert of the Band at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom. The event, which featured appearances by such guest artists as Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Van Morrison, Eric Clapton and Joni Mitchell, may have been memorable all on its own, but, for Maslow, the making of the film was equally unforgettable.

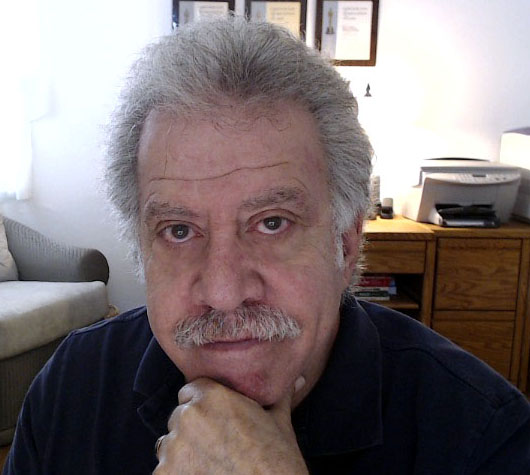

Steve Maslow today.

The Last Waltz was originally booked for a two- or three-week mix at Room D at the Samuel Goldwyn Studio in LA, but once work began by Maslow and his colleagues, including fellow re-recording mixer Bill Varney, those plans were scuttled. “They realized they couldn’t get it done in that time,” Maslow says. “No film in my career took the length of time that this film took. The other film that came close to that length was The Great Gatsby [2013], which was a three-month mix.”

Although the time taken to complete the mix was almost unprecedented in Maslow’s career, the documentary film’s subject matter felt like home turf.

A native of Los Angeles, Maslow was attending California State University-Northridge when he received an offer from his friend Mark Weitz, who was the keyboardist of the band Strawberry Alarm Clock. “I couldn’t figure out what I wanted to do,” Maslow recalls. “Everybody else had a goal but me. I was in college because I thought it was the thing to do, and it kept me out of the draft. I went to a birthday party at the house of Mark Weitz, who asked me if I wanted to go on the road with them as their equipment roadie. I said, ‘Sure, why not?’”

Joni Mitchell, left, Neil Young, Rick Danko, Van Morrison, Bob Dylan and Robbie Robertson in The Last Waltz. Courtesy of United Artists.

The experience was a game-changer for Maslow, who left school and entered the music business. “It opened a whole new world for me because I didn’t know about recording and recording studios,” Maslow concedes. “That’s how I transitioned from the roadie to records.”

He became a recording engineer, working on hits including “December, 1963 (Oh, What a Night)” by the Four Seasons. But, in 1977, as the “garage punk sound” was gaining in popularity, Maslow found himself at a crossroads. “The groups I was working with were doing home-based stuff, so they didn’t come into the recording studio, where you paid $165 an hour and booked it for a month,” Maslow comments. “That started to dry up for me.” So he decided to make the move to the movies. “After I got the IATSE card, I called them up and said, ‘I’d like to be put on the roster for available work,’” he says. “Samuel Goldwyn Studio called me shortly thereafter. I was there for almost 15 years.”

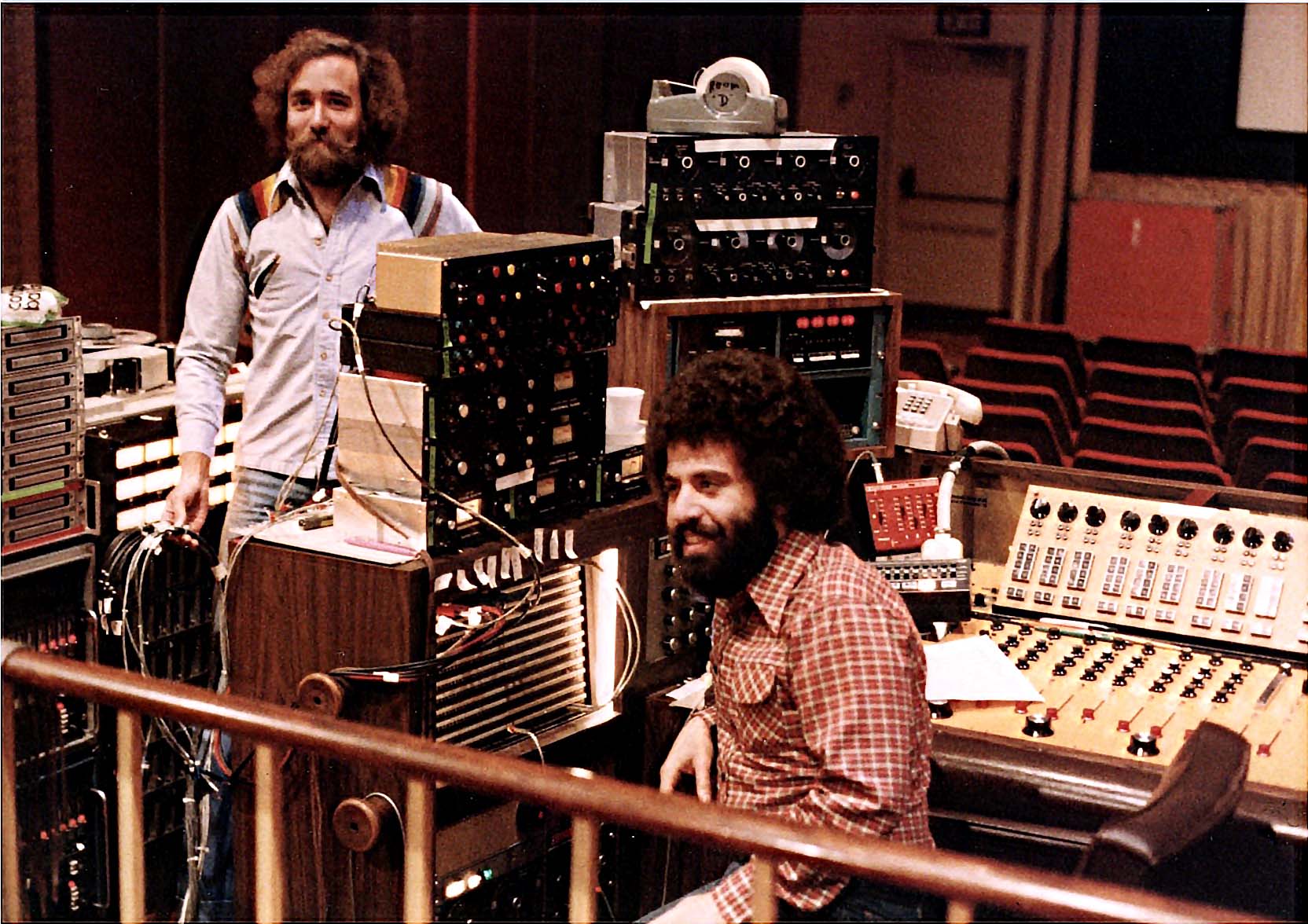

Re-recording mixer Steve Maslow, right, with recordist Bruce Bell on the Goldwyn mix stage D working on The Last Waltz in 1978. Courtesy of Steve Maslow

Maslow — who focused exclusively on mixing music until the early 1990s, when he added dialogue to his repertoire — faced the task of having to consider picture as well as sound. “Recording records, I mixed the way I thought the tune should sound,” Maslow explains. “With film, it’s a matter of making the music work with an image as emotional content: When they kiss, push the music up. When they stop kissing, pull it down. When I was working on Raiders of the Lost Ark [1981], I didn’t know who ‘Indy’ was because I wasn’t following the story. All I knew was that when Indy stopped talking at 365 feet, I made a push on the music.”

Because he was associated with the Goldwyn mix stage, he didn’t have to angle for assignments; instead, projects — including his second, The Last Waltz — came his way. “It wasn’t like it is today, where you book a stage and then pick your own people,” Maslow reflects. “When you booked Room D, you got that crew. [Goldwyn post-production head] Don Rogers knew my background and thought that The Last Waltz would be a perfect vehicle for me to get into.”

The Band — Richard Manuel, left, Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko, Levon Helm and Garth Hudson — in The Last Waltz. Courtesy of United Artists.

Studded with stellar songs like “Up on Cripple Creek,” “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” and “The Weight,” the project was a good fit for Maslow, but the re-recording mixer quickly learned that the job was not going to be finished on the original [three-week] schedule. “They couldn’t stay longer than that, however, because there were other shows booked,” Maslow says. “They decided, ‘Well, let’s mix at night.’ That way, they didn’t have to get kicked out.”

For starters, the film’s technical innovations presented challenges. “During that era, most films were on mag,” Maslow explains. “The Last Waltz came in on 24-track, so it was a job hooking up two 24-tracks to the film chain so I could pre-mix all the music from one 24-track to another 24-track.” Two months alone were dedicated to pre-mixing. “Once we got that done, we had to take the pre-mixed second 24-track and transfer that to a 16-track,” Maslow continues. “That 16-track was then transferred to the mag so that we could hang the mag units against dialogue and effects, which were minimal. That way, it would run on the film channel like it normally would.” The film was mixed using a Quad-8 console. “It had three faders, and below the three faders was a rotary pot, three more faders and another rotary pot,” Maslow offers. “It was very primitive, but it worked.”

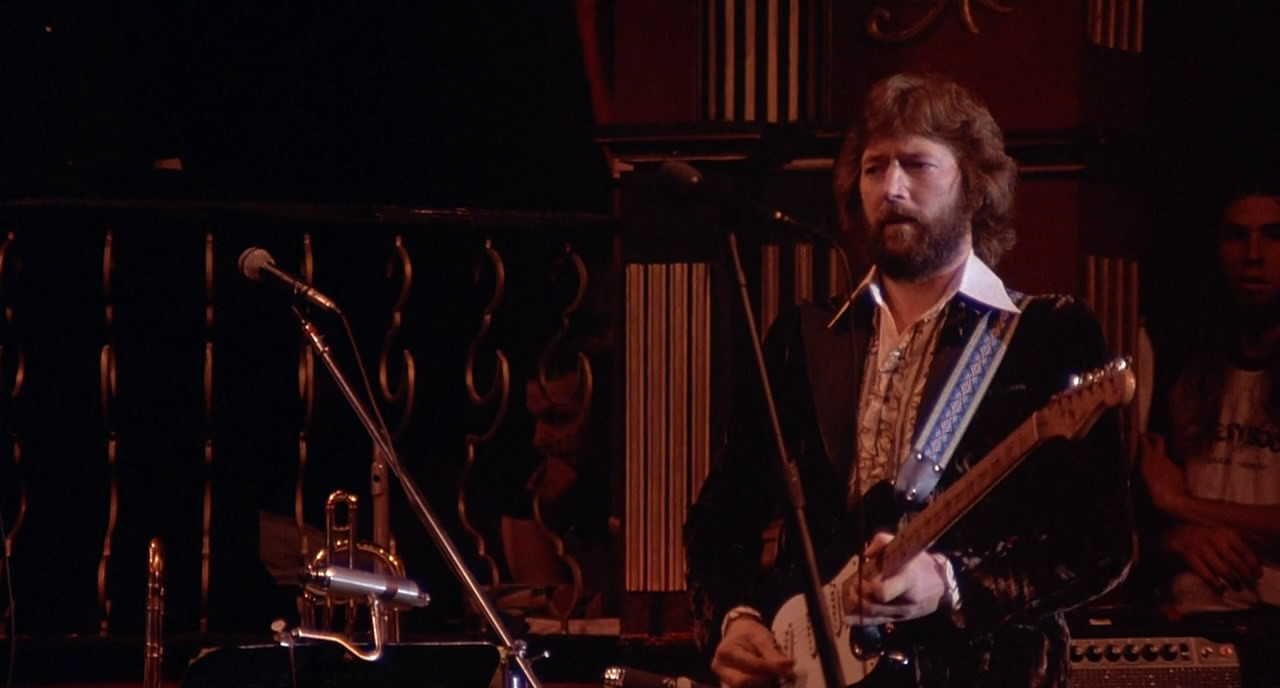

The Band’s Robbie Robertson at the mixing console on the Goldwyn mix stage D during the re-recording of The Last Waltz in 1978. Photo by Steve Maslow

Along the way, members of the Band weighed in on the film (and their work in it). Robertson, who also served as a producer on the film, visited the stage, as did Hudson. “Rick Danko decided after the concert that he didn’t like some of his bass performances, so he overdubbed all his bass parts without regard to picture sync,” Maslow remembers. “I was told, ‘When Rick Danko is onstage, use the production bass, but when he moves offstage, switch to the overdub bass.’ It was maybe two weeks of doing that.”

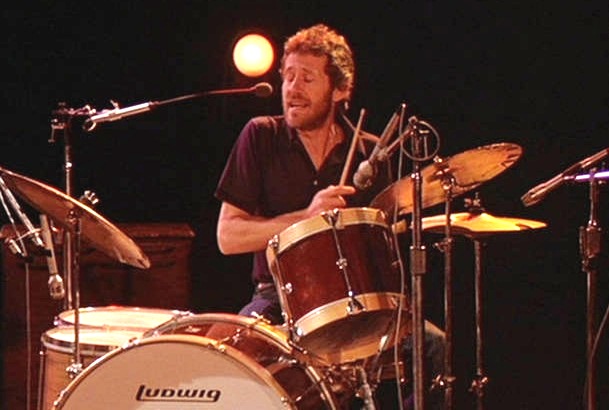

Also the subject of negotiation was Helm’s drumming. “I Keypex’d all of the drums to try to tighten up the sound so there wasn’t so much leakage,” Maslow recalls. “One of the sound supervisors said, ‘Are you Keypexing the drums?’ I said, ‘Yes, I’m just trying to… ‘He said, ‘Oh, no, I like the old,’ so I had to undo two weeks’ worth of work.”

Levon Helm in The Last Waltz. Courtesy of United Artists.

Meanwhile, Scorsese, fresh off of making his classic films Taxi Driver (1976) and New York, New York (1977), was certain about how the film should look and sound — namely, that the audio should dim or increase depending on the angle of the shot. “There was a request that when Levon was singing and the camera was panning stage right, his vocal would drift to the left and the other singers would come in from the right,” Maslow explains. “When I mixed records, you mixed the vocal, but lead vocal was always a lead vocal. Here, things had to move if the camera moved.”

The technique was noted in Janet Maslin’s otherwise-mixed (no pun intended) review in The New York Times. “One exquisitely edited sequence of the Band performing ‘The Weight,’ filmed on a soundstage by cameras that sway and rotate with the music, infuses the interaction of a rock band with more joy and lyricism than any other rock film has ever approached,” Maslin wrote, praising the work of picture editors Jan Roblee and Yeu-Bun Yee.

Joni Mitchell and Neil Young in The Last Waltz. Courtesy of United Artists.

To make the anticipated release date in April 1978, Maslow maintained the schedule of a night owl. Work usually began at 7:00 in the evening and continued until early the following morning. “Every day was a different song or a song we pre-mixed before,” Maslow recollects. “On the first couple of nights, I got a little sleepy, but it didn’t seem that grueling. I got home around 6:00 or 7:00 in the morning and slept until about 1:00 in the afternoon.” During his stint on the film, he only took off Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s Day.

The hustle proved worth it. Writing about The Last Waltz nearly 25 years after its debut, Chicago Tribune critic Michael Wilmington judged it, without equivocation or hesitation, “the greatest rock concert movie ever made.” For his part, Maslow is slightly more measured. “I haven’t seen it in the last couple of years, but it still holds up,” he says. “Sometimes they play it on New Year’s Eve, and I’ll watch it then.”

Eric Clapton in The Last Waltz. Courtesy of United Artists.

And the success of the film helped sway the re-recording mixer to leave records behind for good. “The record industry was getting a little lean, so I stopped doing records and went right into films,” says Maslow, who would go on to receive Academy Awards for his work on The Empire Strikes Back (1980), Raiders of the Lost Ark and Speed (1994). “I thought, ‘You know, this film business looks pretty good.’”

Yet he agrees that The Last Waltz was a once-in-a-lifetime experience. “Not because I worked on it,” he comments, “but because it was a different kind of concert film.”