by Stephanie Argy

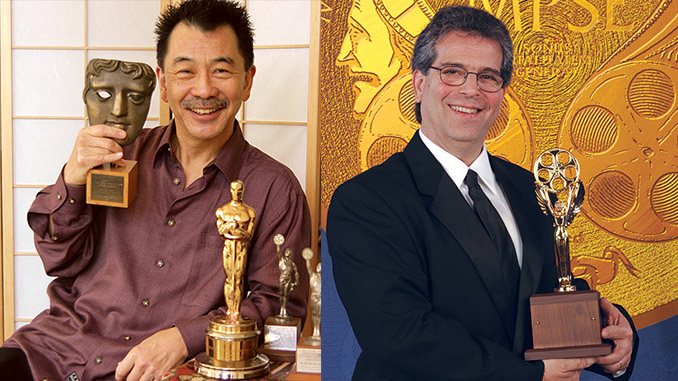

Film editor Richard Chew and music editor and composer Curt Sobel first met on Risky Business in 1983, and since then have worked together on three other films: Men Don’t Leave, Hope Floats and I Am Sam. Chew’s other credits include The Conversation (co-editor), One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (supervising editor), Star Wars (co-editor), That Thing You Do! and Shanghai Noon. Sobel’s credits as a music editor also include An Officer and A Gentleman, The Insider and X-Men. His credits as a composer include Alien Nation and A Cool Dry Place. In this conversation, they talk in detail about the process of music editing and how they’ve worked together to tell a story with music.

Curt Sobel: Thinking of each of these films we’ve worked on together brings back some wonderful memories. Every time I mention that I worked on Risky Business, the first scene people remember is the underwear scene that launched Tom Cruise’s career.

Richard Chew: I was impressed by how the writer/director, Paul Brickman, enhanced his script with his camera compositions and staging. For that scene of Tom Cruise dancing in his underwear to Bob Seger’s “Old Time Rock ‘n’ Roll,” Paul shot the entire dance hand-held, but for the end of the scene, he framed a wide shot of the front of the house with Joel rocking out, silhouetted against the curtains. Later, in editing, he had us add the sound effect of a neighbor’s dog howling. That cracked us up.

Sobel: When Cruise’s character takes out his dad’s Porsche for the first time, a Jeff Beck guitar cue starts. Then the engine dies, and the guitar cue unexpectedly quits, too. There was always audience applause after that scene. Another favorite scene of mine was the erotic train scene between Cruise and Rebecca DeMornay. I loved the way it ended with the soft sound of the electric spark, which conveyed so much more. Very sexy.

Chew: Paul wanted that sequence to look different from the rest of the movie and encouraged me to discover a stylistic way to convey the couple’s lovemaking with sensuousness but without explicitness. I fooled around with reprinting frame speeds and using short fades to black. These were the days before the Avid, so we had to make a lot of trial opticals on black and white reversal. Of course, the other strong element was the music. I temped with Steve Reich and Phil Collins, but Paul thought he could use Tangerine Dream for the final.

Sobel: Their music became a terrific complement to the film. On previous shows, like Thief, Tangerine Dream had sent their unmixed tracks to the dubbing stage. This gives the filmmakers a lot of flexibility, but it can also create too many choices for the final dub. Because of our tight schedule, when we recorded them in Berlin, Paul, Jon Avnet [the producer] and I sat at the board with them and finalized the mixes there.

Tom Cruise in Risky Business. Copyright The Geffen Company

Chew: Let’s flash forward 15 years. Hope Floats was the second film I edited for director Forest Whitaker, and he was intent upon producing a hit sound track to accompany the picture.

Sobel: Forest was interested in using songs to help tell the story, rather than a traditional score. But after screening it, I noted opportunities for score in addition to songs. Using a song can be extremely effective over a montage, to communicate to the audience what the characters may be thinking or to convey emotion not necessarily clear on the screen — sub-text. But sometimes the lyrics get in the way of the dialogue. I shared my thoughts with Forest and got him interested in what I could put together. I ended up pulling most, if not all, of the temp music from The Cure, a score by Dave Grusin. It seemed to have the right emotional depth, orchestra size and “countryish” sound. Forest thought it was so perfectly suited to the film that he then asked Dave to come on board as composer. So there was an example of temp music having a strong influence on the director’s choice of composer. My other role in that film was to find songs that would work throughout the movie. Bob Dylan had just come out with the CD Time Out of Mind, which had the song “Make You Feel My Love.” That worked really well in a dance sequence between Sandra Bullock and Harry Connick. Later, when Don Was joined our post team as music supervisor, he brought on Garth Brooks, who re-recorded the song. Don also brought in songs from The Rolling Stones and Lyle Lovett. The soundtrack album became a hit, and Garth’s version of the Dylan song got a lot of airplay. Forest got his hit soundtrack wish.

Chew: When did pop songs start to be used more extensively as score? There was The Graduate, using Simon and Garfunkel, and Easy Rider.

Sobel: I’ve always thought that Easy Rider started that trend.

Chew: The songs reflected the popular culture at the time and were used so ingeniously to drive the story forward. American Graffiti also used songs to define time and place and create atmosphere. They helped you identify those characters so solidly. But I feel that the filmmaker who’s really used pop songs successfully throughout his career is Martin Scorsese. He uses them with a sure hand to establish and reveal character and to set time and place.

Sobel: Goodfellas was a great example of that. The whole film, wall-to-wall, was source, with each song doing its part. Another fine example of song usage was in Tootsie, when the Stephen Bishop song plays over Dorothy’s visit to the family of the woman he loves. I was involved in a film called Cast a Deadly Spell, for which I composed the score and co-wrote several songs with lyricist Dennis Spiegel for on-screen vocal performances by Julianne Moore. She plays a lounge singer who may still be in love with a detective played by Fred Ward. She’s on stage singing a song and hinting about their failed relationship, and he leaves the club and goes searching for some information that will help solve the mystery. The editor, Dan Rae, used the entire two-and-a-half minute version of the song over the montage, giving more depth and meaning to the detective’s search and the singer’s forlorn state. HBO wanted to cut the song way down and not make it a such a show piece, but the director, Martin Campbell, insisted the song stay in. For that I’m naturally very grateful. It won the Emmy for Best Song that year.

“Given the emotional story and performances [of I am Sam], I wanted to find an underscore that would say something about Sean Penn’s character but not compete with his acting.” – Richard Chew

Chew: Do you find that you frequently have to replace existing songs with different ones recorded by the current hot band?

Sobel: Occasionally. And it’s not just songs. It can happen to complete scores or parts of scores. It’s really a function of time, cost, legality and relationships. It can be frustrating to suddenly have to replace something that works well, but it’s not necessarily a bad thing. It’s all part of the creative, collaborative process and the fluidity of filmmaking. A tie-in with the release of an artist’s new CD or a single that’s on the air can do much to help a film’s visibility. Ultimately, you hope that the new choices do what the old ones did, creatively, emotionally and dramatically. But I tell you, I’ve put in so many songs that somebody thought were from the next great “wonder boy” group — and you never heard from them again. It’s all so subjective.

Chew: There are many interested parties, other than those that really support the movie, who are trying to get directors or producers to use a particular song — where the parallel purpose for making the film is to manufacture a hit soundtrack. In addition to getting the scenes right, it’s always, “Let’s find songs that might be hits.”

Sobel: On one picture I did, we were nearly finished with the final dub when the studio sent over music from their catalog. They wanted their songs placed in the picture and all the existing songs taken out. This had been cleared with the director, but it was after deals had been made and licenses acquired. Maybe money was getting tight near the end, or an album deal had been made, or the producer had a relationship with the studio that superseded the director. So many variables determine how a song gets in or out of the movie. You just hope that the integrity of the film comes first in everyone’s mind.

Chew: Here’s an example of one way filmmakers can deal with decisions made by someone outside the picture to include something: there was a song in Hope Floats that we had to put in at the last minute for some reason. So we mixed it way down –you could barely hear it — it was coming from a radio down the hall as the characters walked past. That allows them to say on the CD that it’s in Hope Floats, though you could probably watch the movie four times and still not hear it.

Scene from Hope Floats. Copyright Twentieth Century Fox

Sobel: Like anything else that can help identify the picture for an audience, a song is a marketing tool.

Chew: When Wild, Wild West came out, the trailers gave the impression that hip-hop was going to be used in this western. I thought, “That’s cool. I want to see this. How do you use hip-hop in a western?” So I went and the entire movie was scored with Elmer Bernstein’s score. Will Smith does a hip-hop song over the tail credits. I thought, “Give me my eight bucks back, I didn’t come to see that! An end credit song doesn’t count!” I was very disappointed. If you find a song that you can use, whether it’s Celine Dion or Will Smith, sometimes it’s like sprinkling holy water on a film to bless it before you send it out into the world. “Good luck! Have good feng shui!” It also says a lot about the demographic for these movies. Obviously, these songs usually appeal to a younger audience. A soundtrack may not impress an older audience, because they’re looking for content or a particular star.

Sobel: One recent action film I worked on had to address that issue. The director had a dramatic score written for the movie, and no songs anywhere on the soundtrack. But the producers decided a song CD that would appeal to a younger audience would be a great thing for the movie. They made a deal with a label and used their artists, all great acts. That meant finding eight to ten places in the movie to put songs, and there weren’t any. Or so we thought. The issue then became what underscore do we consider tossing out and replacing? The director did make compromises, and we found areas where the songs could replace the score. That was certainly not his intent in making the film, or in scoring and mixing the film, but he went along with the decision. His feelings about the film changed at the last minute, and he decided that it could become something that younger audiences might want to see if it had some hip, contemporary songs. But on the other hand, if you can find a song that works well with the characters and has dramatic impact for the film, why not use it? It’s just another approach to scoring the movie.

Chew: That’s the only situation in which I would be willing to use it. In the script for I Am Sam, Jessie Nelson, the director/co-writer, had written in certain Beatles songs. As I began putting the film together, I found and placed other Beatles songs that fit so well that Jessie never questioned them.

Sobel: But there were licensing issues and a cost factor that complicated the availability of the original Beatles songs, so they had to be replaced with newly recorded covers [by Sheryl Crow, Sarah MacLachlan, the Wallflowers and others]. For the final dub, I recut the covers to make them as close as possible tempo-wise to the originals, because you had already cut the picture to the original songs. I enjoyed the challenge of making minute tempo changes with imperceptible edits to try and keep the integrity of the original concepts intact.

“Having a relationship with a director who really knows music is a tremendous plus, and it makes a film delightful to work on.” – Curt Sobel

Chew: I was in love with the original Beatles songs and never thought I would accept the covers. But as each song came in, I was blown away. We were extremely lucky to find a record label like V2, which pulled together artists of such magnitude so quickly. What they did is almost unheard of. But as it turns out, their involvement became very profitable for them. The CD of Beatles covers was a hit, independent of the movie.

Sobel: Soundtracks can help sell the films, and occasionally a soundtrack is as successful as the film, or sometimes even more so.

Chew: On I Am Sam, my other focus was to indicate what kind of score would work with those songs. Given the emotional story and performances, I wanted to find an underscore that would say something about Sean Penn’s character but not compete with his acting, and which would be consistent with the feeling of the Beatles songs. So early on, I used some cues from Penguin Cafe Orchestra, which suggested innocence and joy at times, but the inevitability of tragedy at others.

Sobel: Those songs had such a unique subtlety to them and provided a great template for those scenes. But after our spotting session, there were still many areas left without score, and Jessie felt the musical soul of the film had yet to be found. My task then was to help her search for an appropriate direction for the final score via the temp music. Tracking helps a director answer so many questions about subtlety, space, size, texture and placement. I found a lot of good music, a lot of alternates, which helped resolve many of these issues for Jessie and for the eventual composer, John Powell. Even the starts and stops of the cues were used as templates for the final scoring. He blended the strong elements of the various temp ideas and created a truly original, innovative score. It had to be so subtle, to enhance but not interfere with the terrific performances.

Chew: I thought the way you and I worked together on that picture was just perfect. I was able to introduce some initial ideas for the underscore, then you took over and worked with the director separately. There is only so much time in the day, and I’d rather spend it cutting scenes. And when Jessie was finished with me for the day, she could go over and work with you in your studio and concentrate on the music.

a scene from I am Sam. Copyright New Line Cinema

Sobel: That is often the scenario for how I work with editors and directors. At some point, I take over handling the music or the form of the soundtrack for temping. I work with the editor for changes and for other ideas, but certainly I’m a more hands-on liaison with the director regarding the music.

Chew: Do you find yourself getting involved earlier these days than you used to?

Sobel: I do. As a matter of fact, this week I’m working on a future project of Ivan Reitman’s. He and I put together a montage of 12 or 13 songs for a film that he’s hoping to shoot, to help him formulate what he wants musically before he starts shooting. But typically I am brought on to temp once they have started shooting or after they finish. Sometimes I come in after two or three unsuccessful attempts at a temp. There are so many variables. When you’re showing a cut to a director or to a studio, catching them at the right time of day can sometimes influence them more than whether it’s working or not. Did they just come out of an intense meeting? Mornings seem to be better than afternoons.

Chew: Do you ever see early cuts without any music at all?

Sobel: Absolutely. A good example of that was on Evolution last year, another picture I did with Ivan. He brought me on five or six weeks before they finished shooting, and he would send me cut scenes that the picture editors, Shelley Kahn and Wendy Bricmont, had put together. I would come up with a variety of suggestions, including large orchestra, small orchestra, synthesizer, a combination. I would go to the set and bring him these ideas on video, and he’d decide which ones he liked. A few weeks after they wrapped, we had a director’s cut temp dub. That worked so well because early on, I was able to help define the direction of the music with him. Of course, you need a budget to be able to bring someone on that early.

“The songs reflected the popular culture at the time and were used so ingeniously to drive the story forward.” – Richard Chew

Chew: Music is the strength of some directors and a weakness in others. Some directors, like Paul Brickman, Cameron Crowe or Forest Whitaker, have such strong musical instincts that I follow their lead. On Waiting to Exhale, even before Forest Whitaker hired a cinematographer or editor, he had hired Kenneth “Babyface” Edmonds to write songs. Early on, instead of working with a music editor, I was giving cut scenes to Babyface on tape, and he wrote his music exactly to the beats of the scenes. Every few days, I would get back CDs with songs that he had sketched in, when I hadn’t even finished editing the film. That guy is like a music machine! But other directors may not have thought of music at all and rely on me to introduce musical ideas.

Sobel: It’s a thrill to work with directors who are extremely musical. Ivan has a great ear, and so does Taylor Hackford, whom I’ve worked with for over 20 years. Having a relationship with a director who really knows music is a tremendous plus, and it makes a film delightful to work on. We don’t need to talk about any directors who do not have that musical ability.

Chew: We don’t know who those are.

Sobel: Right. I don’t think they exist.

Editor’s Note: Too see more of this interview, read part 2.

Comments are closed.