Hollywood Sound Design and Moviesound Newsletter:

A Case Study of the End of the Analog Age

by David E. Stone with Vanessa Theme Ament

Focal Press/Routledge, 2017

Hardcover, 382 pages, $113; eBook $54.95

ISBN #978-1-138-89064-0

by Betsy A. McLane

The pages of Hollywood Sound and Moviesound Newsletter are dusted with bittersweet nostalgia. Authors David E. Stone and Dr. Vanessa Theme Ament lived and worked in Hollywood’s post-production sound world during the 1980s, ’90s and early 2000s. Stone was a sound editor on dozens of major television shows and feature films, beginning as a sound effects editor in the 1970s at Hanna-Barbera. He won an Academy Award for Sound Effects Editing for Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992). Ament started as a Foley artist in 1980, working chiefly in that role, on many well-known movies and television shows into the early 21st century, and authored the book The Foley Grail (Routledge, second edition, 2014).

The two were married from 1990 until 2010, and from 1989 until 1994 they produced Moviesound Newsletter (MSNL), a product of the do-it-yourself ‘zine era of desktop publishing. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines a zine as, “a non-commercial, often homemade publication usually devoted to specialized and often unconventional subject matter.” That describes well the intent and tone of Moviesound Newsletter — a labor of love that provided a much-needed platform for ruminating with interested others about post-production sound in the pre-Facebook, pre-blog era. Ament is credited as publisher, with Stone as editor and chief writer. Anyone with interest and expertise was invited to submit writing.

The period during which the newsletter circulated was a critical and tumultuous one for movie sound. It was clear to all that digital would ultimately replace multi-track analog, but no one knew when, or in what format. In the meantime, there was increasing pressure to create “big sound” multi-track movies, the type of blockbusters that need audience-engulfing effects, such as Terminator II, Backdraft or Hook (all 1991).

This required sound technicians to push ever harder to master and expand upon existing analog systems, experiment with digitization, master changing formats, and reconfigure workflow. It was also a time when studios and theatre owners faced increasing demand from audiences for better sound experiences. Once THX began demonstrating high-fidelity standards for theatres in 1983, “the audience [was] listening” — and reconfiguring cinemas became another economic burden on the industry. Add to this the growing recognition that film sound from older films needed to be “restored” for burgeoning home video markets (especially the cinephile’s dream, laserdiscs), and Hollywood found itself facing an overload of pressures that rivaled those of the transition from silent to sound era.

Browsing through Stone and Ament’s book, it becomes clear that the professionals who loved and worked in post sound then had learned and adapted quickly, but that many paid a very steep price to keep up an increasing pace. “It’s not the long hours, it’s the stress.” Leo Chaloukian, owner of Ryder Sound from 1976 to 1996, told Moviesound Newsletter while recovering from a heart attack in 1992.

Mention of stressors pops up throughout the 12 “Reels,” as chapters of Hollywood Sound Design are called. There are tributes to colleagues who died, such as pioneer Murry Spivak, who began his long sound career in a pit orchestra creating effects on percussion instruments to accompany silent movies, and Alan Splet, who was part of the 1970s film sound revolution.

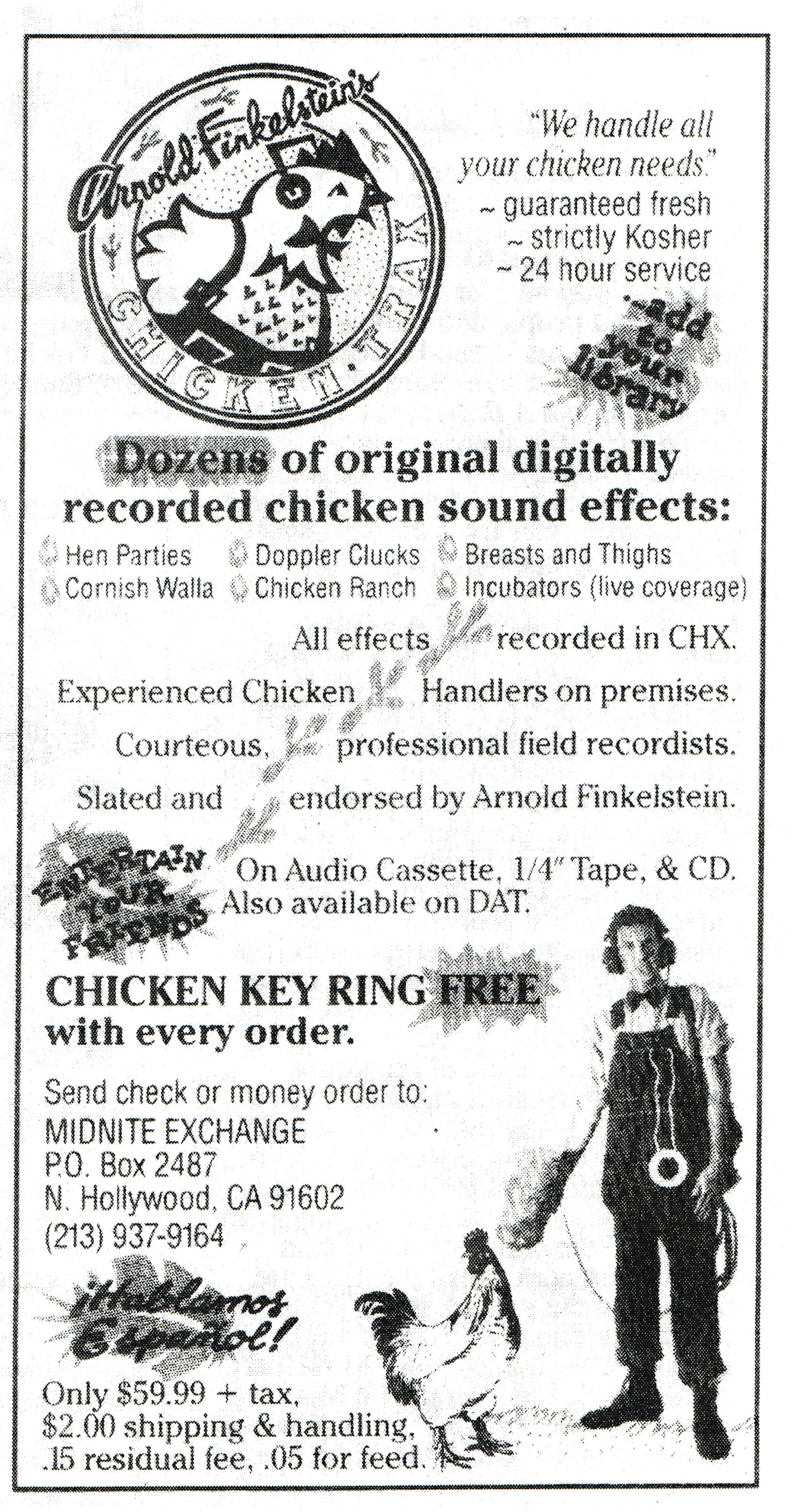

There is also plenty of playfulness and anecdotes that will ring true to those who spend their work lives in editing rooms. The humor is naturally of the techno-geek sort, and although it pops up throughout the book, most of the funny business is collected in “Reel Ten: Unsound Thinking.” For example, the April 1990 issue reported on an analysis of “the subjective effect of eating certain foods while watching a movie. Dozens of ‘double-gagged’ tests implicate unsalted, non-buttered popcorn in creating the perception of a flat-frequency audio response. Possibly movements of the head and jaw contribute, but the influence of anhydrous butter on mid-range cancellation is not known.”

Located adjacent to this article is a reproduction of “the only advertisement that MSNL ever printed,” promoting Arnold Finkelstein’s Chicken Tracks — “dozens of original digitally recorded chicken sound effects, available on audio cassette, quarter-inch tape and CD. Also available on DAT.” Included are Hen Parties, Doppler Clucks, Cornish Walla — all recorded in “CHX.” There are a few other images in Hollywood Sound Design; hopefully these are reproduced in better quality in the eBook than in the hardcover edition.

MSNL subscribers included non-professional audiophiles who sought a source for information on the latest and the best for their home systems in a time before many consumer magazines or the Internet offered knowledgeable evaluation. “Reel Seven: Critical Listening” is mainly devoted to laserdisc reviews of individual titles that highlight sound and ponder important aesthetic questions about obligations to original sound quality and the expectations of modern audiences. Like almost everything else, these are clear and perceptive, contributing to an overall tone of competent writing.

The book also provides serious comment on the ways that sound departments and their professionals — both during recording and in post — are often disregarded by studio executives and even some filmmakers.

The book also provides serious comment on the ways that sound departments and their professionals — both during recording and in post — are often disregarded by studio executives and even some filmmakers. MSNL contributors were involved in gaining proper credits for sound personnel, and in taking to task those who abused workers. An especially critical editorial published in July 1989, excoriates director James Cameron and producer Gale Anne Hurd for their treatment of post sound on The Abyss (1989):

“The supervisors [then-sound editor] Dody Dorn[, ACE,] and Blake Leyh had barely enough money from Hurd to hire a handful of inexperienced non-union editors. Eager to please and to make their mark on a ‘Big Movie,’ they bravely faced an overwhelming pile of complex dialogue and big sound FX. As is common with this type of film, incessant picture changes required the rookies to stay up many nights and weekends adjusting their tracks. A union crew would have been compensated for that time. Eventually, five experienced ADR editors were added to the crew, creating a mixed union/nonunion shop… The Editors Guild stepped in and signed everyone to the union. The happy ending is that many neophytes joined Local 776 [now 700] and learned that they had a right not to be exploited again. Gale Hurd, you’re already a rich kid. Do you have to make craft people mess up their lives to make you richer? Jim Cameron, we know you’re a macho man, and yes, the people you hired are not as tough or smart as you. But they are ostensibly professionals…”

Hollywood Sound Design is much more than a simple compendium of old technologies and gossip from MSNL. The authors organize material by topic rather than chronology, and explanatory mini-essays place the excerpts in historical context. The subject is not sound theory, or how-to; the greater aim of the book is to provide an accurate historical record and inspiration for film historians, scholars and students of sound.

There is also a guide on how to best use the book, as well as several useful, if specialized, appendices, including “Further Reading” and “Laserdiscs as Transition and The Couch Potato’s Guide to Laser Sound.”

Both Stone and Ament transferred their enormous knowledge and experience into academe; he is a Sound Design Professor at Savannah College of Art and Design, and she is the Edmund and Virginia Ball Endowed Chair, Professor of Telecommunications at Ball State University.

With the over-$100 price tag for the hardcover book, this is a text that may be most purchased by libraries, but the $55 eBook is a valuable resource for everyone who works in or cares about the quality of sound in motion pictures, television and games.