story and photos by Joseph Herman

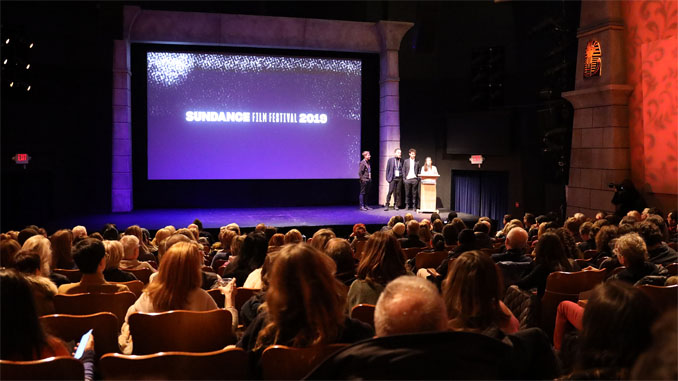

Sundance, the largest independent film festival in the United States, takes place every year in Park City, a funky little ski town nestled in the beautiful snow-covered mountains of Utah. It’s an important showcase where both American and international independent films are premiered, friends are made and distribution deals are struck. In 2019, there were over 14,000 submissions to the festival.

This year’s festival also happened to mark an important milestone for Adobe Inc., the well-known and ubiquitous software company that focuses on multi-media creative applications. No stranger to the festival, Adobe has been a major partner of it for more than a decade. However, this year was especially noteworthy for the company since, for the first time, over half of the films at the festival were edited with Premiere Pro, Adobe’s versatile motion picture and video editing application. The official number, according to Adobe, was 52 percent, consisting of 98 films — a four-fold increase over the past five years.

Premiere’s Emergence

It wasn’t always like this for Premiere. While other Adobe flagship programs have long dominated their niches in the creative market, Premiere Pro’s widespread acceptance by motion picture editors the world over is relatively recent. Some Adobe apps, such as Photoshop, have long been the leaders in their respective fields. However, when it came to editing, Premiere, which enjoyed quite a bit of popularity at its inception, somehow came to lurk in the shadows while other editing applications, namely Avid Media Composer and Apple’s Final Cut Pro, took the spotlight.

Premiere has been around practically since the inception of digital nonlinear editing. Here is the original 1991 splash screen for Adobe Premiere 1.0.

No newcomer to the market, Adobe Premiere 1.0 was released way back in December 1991, just a couple of years after Avid unleashed its NLE system, Media Composer, on the Apple Macintosh platform. Buoyed by Avid-branded hardware, such as its proprietary I/O boxes, Media Composer soon became the dominant nonlinear editing system in the film and television industry, changing the way editors did their jobs forever.

While Premiere continued to attract some new users, its popularity on the Mac began to decline after the introduction in 1999 of a new NLE from Apple, Final Cut (its development team included the original programmers of Premiere). The new Final Cut caught on quickly, thanks in part to tight integration with QuickTime and native support of FireWire-enabled cameras.

A sort of market segmentation ensued; Avid continued to dominate high-end motion picture and television editing (and still plays and important role in Hollywood editing suites), but it began to lose share to Final Cut, which became popular among independent filmmakers. Somewhere in the background was Premiere, but not many professional editors were paying attention to it. That is to say, not yet.

Park City’s busy Main Street is a popular place to hang out during the festival, day and night.

That’s because certain events were about to unfold which were to dramatically change Premiere’s fortunes. For starters, improvements to commonly available hardware began to negate the need for expensive Avid-branded I/O. However, one could argue that the real change to Premiere’s fortunes began in 2011 when Apple introduced Final Cut Pro X. With the new version of Final Cut came a new interface that was sharply criticized, especially its magnetic timeline that many professional editors found difficult, if not downright annoying, to use.

Some Final Cut users refused to upgrade, sticking instead with version 7. Eventually, however, they began to look elsewhere. Fortuitously for Adobe, the company had been methodically improving and upgrading Premiere over the past several years, rewriting its code base while adding professional features. To mark its transformation, Adobe even changed its name from Premiere to Premiere “Pro.”

Sundance’s main box office on Heber Avenue.

Former Final Cut users had a choice. They could switch to Avid Media Composer, or try the new version of Adobe Premiere Pro, which many editors hadn’t had a good look at for a long time (if ever). When they did, they liked what they saw. Aside from having a sleek new look and lots of professional new features, Premiere Pro was part of the Creative Suite (soon to be the Creative Cloud).

Why was that important? A lot of people already owned Adobe’s suite of creative applications for After Effects, Photoshop and Illustrator (among others), each of which are trusty applications used throughout the field of motion media. Thus, it wouldn’t cost them a thing to check out Premiere Pro since they already owned it anyway. When they did give it a go, they found that Premiere Pro had evolved into a mature, versatile and accessible editing platform that cooperated well with Adobe’s entire family of applications. For many editors, Premiere Pro was the right product in the right place at the right time.

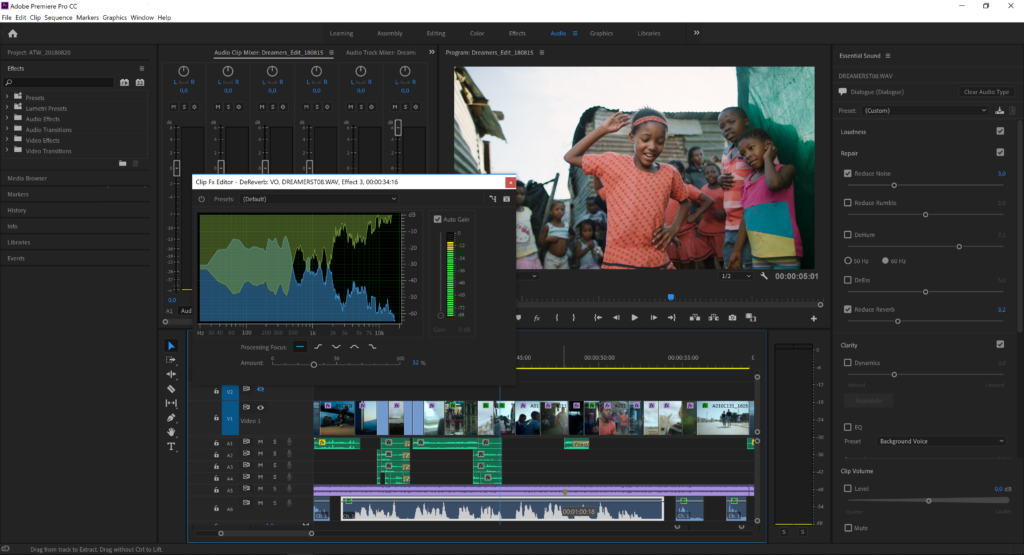

Premiere Pro has evolved into a leading NLE with professional features that motion picture editors turn to daily. It was the editing program used by over 50 percent of the films appearing at Sundance.

Fast forward to today, where not only more than half of Sundance films being cut on Premiere Pro, but Hollywood too has begun to embrace Adobe’s capable NLE for big films such as Gone Girl (2014), Deadpool (2016), Hail Caeser (2016) and others. To spread the gospel to motion picture editors even more, Adobe has recently opened a slick editing suite in LA, built around its NLE, where picture editors are invited to experience cutting in Premiere Pro. They are able to ask any questions and hopefully be convinced to use it on their projects. To what extent Adobe will erode Avid’s entrenchment in Hollywood remains to be seen.

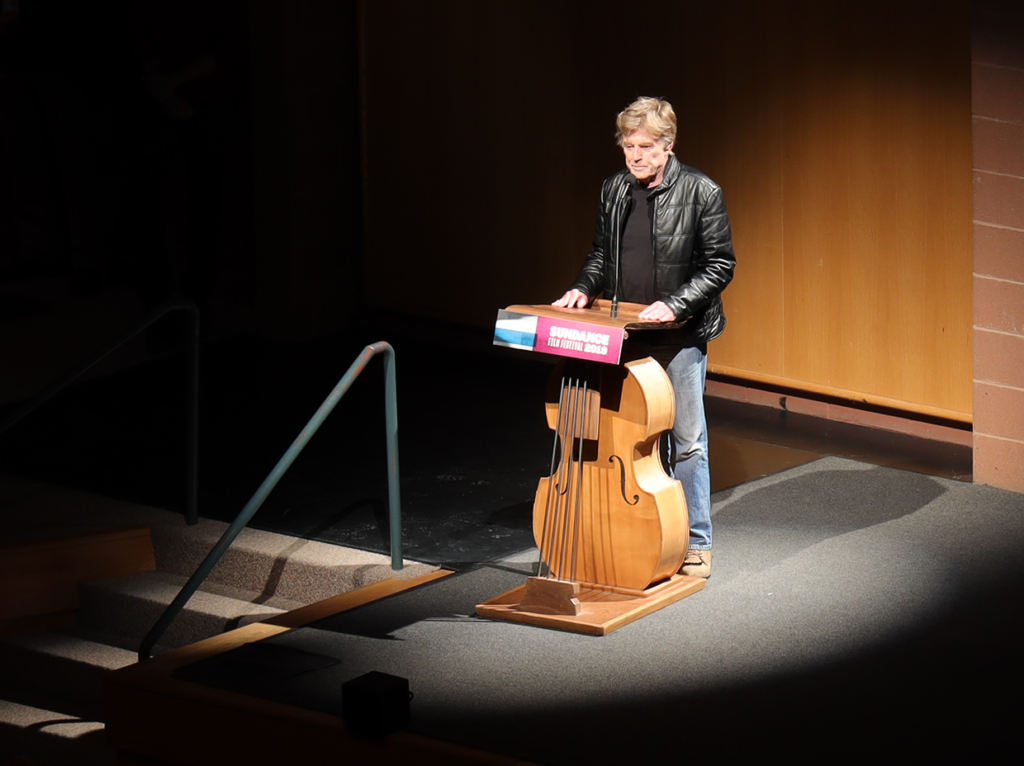

Robert Redford came out to kick off the festival and reminisced about the history of Sundance on opening night before the screening of After the Wedding, directed by Bart Freundlich and starring Julianne Moore, Michelle Williams and Billy Crudup.

Sundance Experience

At Sundance 2019, CineMontage had the opportunity to not only to watch the premiere of movies that were cut with Adobe Premiere, but to interview some of the editors who used it on their films. In fact, this began the week before Sundance when editors Phyllis Housen (Clemency) and Kent Kincannon (Before You Know It) were profiled in the Q1 2018 issue of CineMontage magazine (https://cinemontage2.org/the-sundance-kids-three-editors-and-their-films-make-their-debuts-in-park-city/).

At the screening of Clemency, which went on to win the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance, Chinonye Chukwu (center), the writer and director of the film, as well as the entire cast and crew went up on stage to answer questions and talk about the movie.

When you aren’t attending a screening at Sundance, there’s a good chance you’re spending time somewhere around Park City’s Main Street. Bustling with attendees as well as shops, art galleries, restaurants and a venue to hear live music, Main Street also had pop-up shops operated by companies such as Canon, Dell, Chase Bank, AT&T and Lyft. These promotional corporate storefronts didn’t sell anything, but instead functioned as fun places to hang out, enjoy free snacks and, in the case of Canon and Dell, be exposed to new products, demos and information.

The Canon Creative Studio on Main Street featured panel discussions, displays of choice Canon Cinema gear and the opportunity to talk with cinematographers and camera enthusiasts.

At the Canon shop, officially known as the Canon Creative Studio, there were interesting panels throughout the day with editors and filmmakers. Also on display were some mouth-watering Canon cinema camera rigs that were used on several of the films appearing at the festival. You could also get your picture taken by a professional photographer and talk shop with camera enthusiasts and cinematographers. Speaking of Canon, all the photos in this story were taken on the new Canon EOS R full-frame mirrorless camera, which the company graciously lent CineMontage during the festival.

Some sexy camera rigs were on display at the Canon shop, such as this Canon C300 with a 50-1000 lens that was used to film the documentary Tigerland.

Dell’s pop-up also featured sexy new products and presentations. There, one could meet with Andrew MacDonald and Tristan Cezair, creative directors of CreamVR, who relied heavily on Adobe After Effects and Premiere (as well as 3D software) to develop their own innovative technique to create convincing human avatars for virtual reality and games. Also there was Ross Shain from Boris FX, who demo’d Mocha 2019, the new version of the popular planar tracker and rotoscoping tool, as well as Particle Illusion, a comprehensive particle system for creative visual effects that works with Adobe Premiere Pro and After Effects.

During the festival, Adobe staged “Explore the Wide World of Editing,” a panel about the art, technique and business of editing.

Adobe also conducted the panel discussion, “Explore the Wide World of Editing,” where up-and-coming editors shared their thoughts about the art and business of editing and took questions from the audience. All the editors on the panel used Premiere Pro for their work. That evening was a screening of The Disappearance of My Mother, an unusual cinéma vérité-style film and character study from Italy that was made by the son of a one-time famous fashion model.

John Travis, vice president of Brand Marketing for Adobe, supplied information about Adobe’s partnership with Sundance, such as sponsoring the Sundance Ignite program. Sundance Ignite not only gives individuals ages 18-25 a reduced cost ticket package to the festival but provides events specially curated for emerging filmmakers and the film industry, teaches them about financing and distribution, and exposes them to the creative community.

In addition, the Sundance Ignite Fellowship Program goes further by providing 15 fellows a yearlong experience that kicks off with a free trip to Sundance, where they’re paired with a mentor with whom they will work for the rest of the year. Fellows also receive a complimentary subscription to the Adobe Creative Cloud. To date, 70 fellows have passed through the program, and six alumni have had their short films selected to screen at the 2018 and 2019 Sundance Film Festivals.

We Are Little Zombies is an original film from Japan directed by Makoto Nagahisa, pictured left at the film’s premiere. On the right is Maho Inamoto, the movie’s editor.

In Park City during Sundance, Adobe also rents a cozy little house within walking distance of Main Street. At the Adobe House, I had the opportunity to talk to several editors about their films in a relaxed and informal setting. One was a unique film from Japan for which we attended the premiere called We Are Little Zombies, directed by Makoto Nagahisa. If you enjoy that which is different, perhaps even bizarre, you might want to seek out this funky film about four kids whose parents all have died one way or another, yet somehow manage to form a successful pop music band. Beyond that, this film is rather hard to describe — it has some moments that you just have to see. The film was edited by Maho Inamoto, who works for a Japanese media company that switched its operation over to Premiere Pro from Avid.

Documentary Now! is a unique series of films that spoofs famous documentary films. The editors, Jordan Kim (second from left) and Micah Gardner (third from left) participated in a discussion about editing at the Canon Creative Studio on Main Street.

Other editors at the Adobe House included Micah Gardner and Jordan Kim from the mock-umentary television series Documentary Now! They screened some episodes of the show at Sundance. As Gardner and Kim explained, the show, hosted by award-winning actress Helen Mirren, spoofs famous documentary films by parodying them with a similar but different subject matter. Each show in the series is an entirely new production — its own little film, if you will. It was informative to learn about Documentary Now! by its two editors and how they often utilize vintage cameras and old tape decks to create authentic-looking source material. In addition to using Premiere to edit the series, Gardner and Kim also heavily rely on other apps in the Creative Cloud such as After Effects, Photoshop and Illustrator.

The Academy Acknowledges Adobe

In addition to Premiere’s success at Sundance’s forum for Independent filmmaking, this year the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in early February granted Scientific and Engineering Awards to David Simons, Daniel Wilk and others for the design and development of Adobe After Effects, as well as to Thomas and John Knoll and Mark Hamburg, for the design and development of Adobe Photoshop. Both of those programs occupy important places in many a filmmaker’s toolkit and have been used countless times on all manner of projects from off-beat independent films to Hollywood blockbusters.

Many Sundance attendees stay in ski-lodges such as these, which presents the opportunity to hit the slopes before attending a screening.

Attending Sundance can be an exhilarating experience. It’s great to hob-nob with so many who are passionate about films and filmmaking. It’s even better if you know how to ski, since you are surrounded by some of the best ski slopes in the country.