by Peter Tonguette

Steven Soderbergh and Larry Blake have been making movies together since the start of their professional lives. The supervising sound editor and re-recording mixer on all of Soderbergh’s films — including such classics as sex, lies, and videotape (1989), Out of Sight (1998) and Traffic (2000) — Blake has known Soderbergh since the director was 16 years old.

The two Louisianans — Soderbergh lived in Baton Rouge, where his family moved when he was a teenager; Blake was born and raised in New Orleans — were introduced through a mutual friend, and soon their collaboration got underway. The first film for both was 9012Live (1985), a documentary directed by Soderbergh about the progressive rock group Yes’ concert tour for its 1983 album, 90125.

Soderbergh has never been reticent about adding to his filmmaking workload. The Academy Award-winning director has handled the picture editing of many of his films (when not working with Stephen Mirrione, ACE, as well as other editors earlier in his career). And Traffic saw his duties expand to include cinematographer, too. Those crafts come readily to the director, Blake says, so he has been comfortable taking on both of them.

But, where sound is concerned, Soderbergh has relied on those he trusts, including Blake. Given their long history, it is no surprise that their work together is largely unspoken. “When people ask me how I collaborate with him on sound jobs, they’re usually surprised to find out that a film rarely involves more than a few minutes of conversation,” Blake says. “There’s very little said between us because I have a very clear idea of what he’s going for.”

Their overlapping tastes run to the realistic, perhaps even the minimalistic. “We just don’t have a what-did-I-get-for-Christmas approach towards sound,” Blake says. “As a rule, we’re pretty conservative about surrounds, just because it has such great potential to drag you out of a movie as opposed to involving you.”

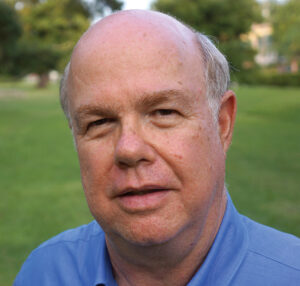

Larry Blake.

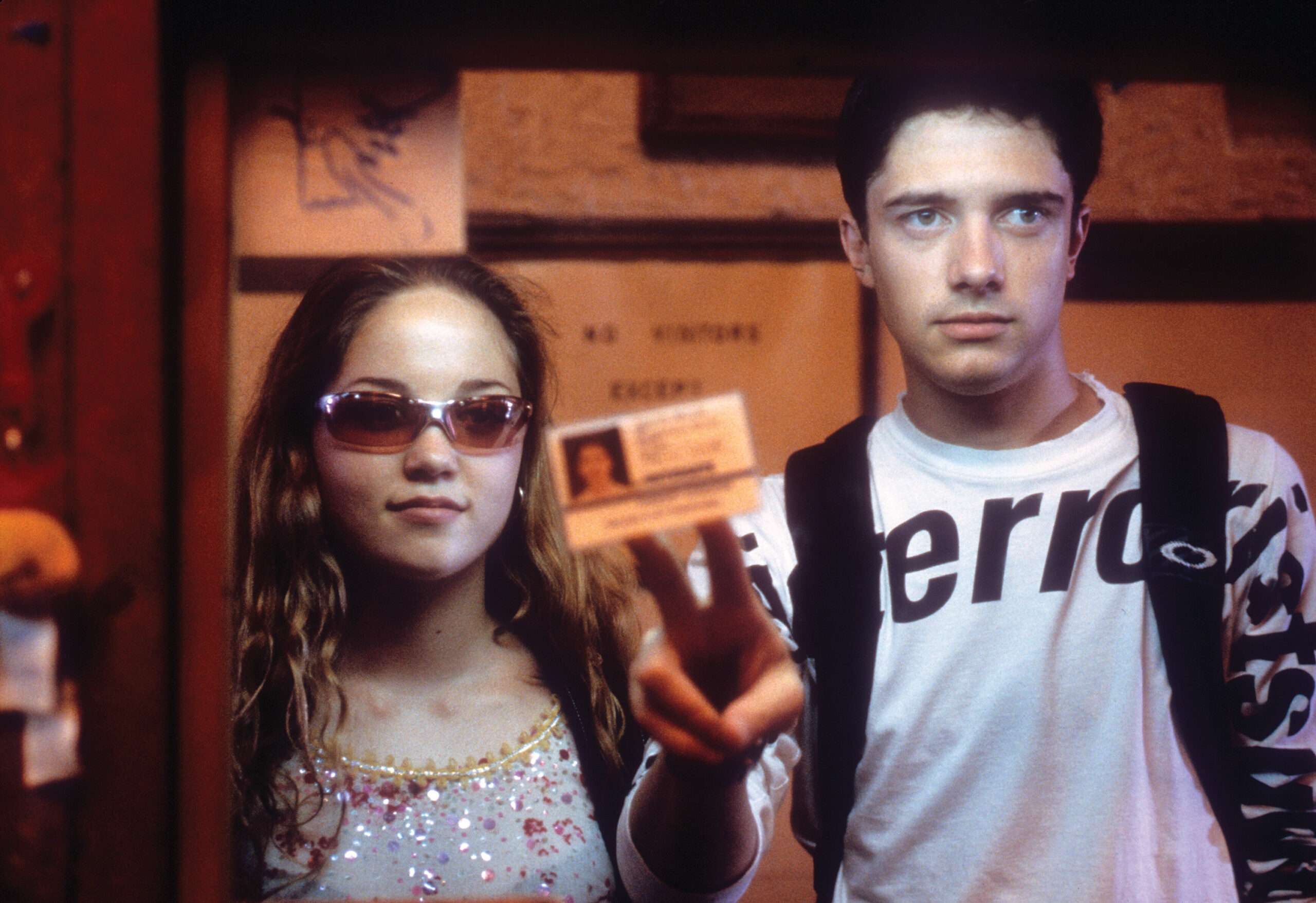

One of the high points of their collaboration is Traffic, which was released 15 years ago to laudatory reviews, receptive audiences and, ultimately, four Academy Awards, as well as a nomination for Best Picture. Screenwriter Stephen Gaghan (who, like Soderbergh, was honored with an Oscar) examines the North American front of the war on drugs through a cluster of characters, including the new-on-the-job US drug czar, Robert Wakefield (Michael Douglas); his daughter (Erika Christensen), who is grappling with addiction; law enforcement agents in this country (Don Cheadle and Luis Guzmán) and in Mexico (Oscar winner Benicio Del Toro and Jacob Vargas); and criminals, including a well-off drug dealer, Carlos Ayala (Steven Bauer), and his wife Helena (Catherine Zeta-Jones).

The film, tangled storylines and all, was not particularly difficult to mix. “It had a scope, but in and of itself, there were no big crowd scenes, no big effects scenes,” Blake comments. But it nonetheless represented a turning point. “It had the most influence on my career in that it was the second movie I mixed completely in the box, within Pro Tools, and certainly one of the first major movies that anyone ever mixed in the box.” What’s more, the film was final-mixed, in the fall of 2000, at Blake’s Swelltone Labs in New Orleans — a newly formed company that had begun its life as Ultrasonic Digital, owned by Jay Gallagher. That year, Blake became the co-owner, with Gallagher, of the renamed company and, after Hurricane Katrina, its sole owner.

The groundwork to this turn of events was laid the previous year, when Blake worked on Housebound (1999). That “sound- design intensive” project was mixed at Ultrasonic Digital, and it was Gallagher who encouraged the use of Pro Tools. “Jay just persisted in convincing me that mixing virtually was the way to go,” Blake says. “Pro Tools and the fundamental principles of mixing in the box were very evident, even though the technology at that time was very primitive compared to what we have today.”

In July 2000, with the principal photography of Traffic complete, Blake broached the possibility of mixing in the box to Soderbergh. “I brought up to Steven the idea that we could mix in this manner, where the Pro Tools sessions would contain all the mix data — EQ, level, reverbs, reverb sends, panning — and that we could then conform it throughout multiple versions,” Blake recalls. “To this day, its efficiency in moving from temps to finals is one of the inarguable benefits of this approach.”

But the decision meant moving sound editing and mixing operations from LA to New Orleans, where Blake made his home and where the team would set up shop at Swelltone. “We went there because we were lashing together four Pro Tools workstations with other automation and mixing right out of the original edit sessions,” Soderbergh said in a 2001 interview with Directors World, adding, “It’s still hard to find [a] mixing stage in LA that can do that.” Blake notes that today, while mix stages built around Pro Tools control surfaces are common, they are still not the norm.

“When Steven did say that he would commit to this approach,” Blake says, “we bought a lot of equipment, including a pair of new Pro Control control surfaces, and then we set about mixing the movie in New Orleans.”

Traffic is a strikingly quiet film; at times, every sound in a scene seems meant to be heard. Early in the film, for example, the audience registers the noise made by the glass in which Robert has a drink — a harbinger, perhaps, of the countless scenes of addiction among other characters to follow. Blake particularly cites the work of production sound mixer Paul Ledford, who used a two-track DAT recorder, and boom operators Joseph F. Brennan and Keenan Wyatt. “It seems like so often production tracks — either because of the design of the movie, the lack of care of the director or a lot of effects that are not organic to the shooting of the movie — are sort of pushed by the wayside these days,” he says. But that was not the case on Traffic. “Paul’s production track is such a huge part of the sound of Traffic that it cannot be understated.”

Larry Blake recording sound in the desert for Traffic in 2000.

Photo by Bob Marshak

Even one of the film’s rare action scenes — a kinetic, chaotic shootout between Cheadle’s and Guzmán’s DEA agents and drug dealer Eddie (Miguel Ferrer) — made it to the screen primarily using Ledford’s production tracks. “We did sweeten it with real gunshots,” Blake concedes. “I’m not going to say we didn’t, but it certainly felt right with just production.”

Blake himself was present for about a quarter of the shooting, recording backgrounds in Ohio and California locations, as well as in Tijuana and Nogales in Mexico. “The backgrounds, especially in Nogales, were integrated seamlessly with Paul’s track, because not only do you need them for the usual creative reasons, but you need to have some sort of cohesive bed on which the movie sits for foreign-language versions,” the re-recording mixer explains.

Because Spanish was spoken in most of the Mexico-set scenes, Blake prepared two M&E mixes: one for markets that elected to preserve the Spanish dialogue and another for those that chose to dub it. “We tried to get countries to take [the former], and we had mixed success,” he adds.

In August, two temp mixes were done at Weddington Productions in Los Angeles in stereo. Ahead of the first temp, Blake assigned 10 dialogue editors to work on one reel apiece in the span of a single week. “I began on this movie what has since then become my standard for all movies,” he notes. “I try to shoehorn the schedule such that we go to the first temp with correctly cut, properly edited dialogue. Not the usual ‘we’re going to replace

it later’ quick and dirty job.” Thereafter, the dialogue was in the hands of sound editor Aaron Glascock, a longtime colleague of Blake and Soderbergh who had previously been a picture and sound assistant.

“Aaron’s contribution, with the dialogue and effects, was critical to the finishing of this film,” Blake says. “Looking back, it’s almost inconceivable to me that I would have gone into these uncharted territories without him.”

In October, mere minutes into the first day of the final mix at Swelltone, another significant decision was made. In the first scene in Mexico, with Del Toro and Vargas, an airplane roars by overhead. As Blake recalls, “I had the plane fly into the surrounds, and Steven said, ‘You know what? Let’s keep this on the screen.’” It was decided to keep all effects in the left- center-right channels. And, when a check screening of the final mix was held at the Samuel Goldwyn Theatre in Beverly Hills, a further adjustment was made. “After the Goldwyn screening,” Blake says, “Steven decided to have all effects [and dialogue] in the center.”

Traffic. USA Films

For his part, Soderbergh recalls Blake coming up with the idea. “Larry said, ‘I think it’s weird with the aesthetic of the movie to have these wide stereo background and effects tracks,’” Soderbergh told Directors World. “He said, ‘We ought to dump everything into the center channel to give it the documentary feel that you’re going after.’” Regardless of where the credit lies, however, both agreed that the film would seem more of a piece after this change.

“He wanted it to feel like the movie was shot with one big mic above the camera,” Blake says. “Obviously, you could never do that in reality, but he just thought that the documentary feel of the movie would be better supported if everything was in the center.” The sole exception was the score composed by Cliff Martinez, which remained in 5.1 and was uniquely utilized by Soderbergh and editor Mirrione (who also won an Oscar).

Many scenes are underscored, but nearly as often, dialogue and effects are wiped from the soundtrack, leaving Martinez’s music to stand on its own. “I remember a specific moment when a car is going through downtown San Diego during the trial where Eddie is testifying against Carlos Ayala,” Blake recalls. “There’s a shot of the camera panning by the courthouse, and we took out all the sound there.” At the mix, Soderbergh wondered if they had “gone to the well” one too many times, but Blake reassured him. “I said, ‘No, that cue at that moment is so perfect.’ Any other sound was not contributing to anything on the scale that Cliff ’s music was.”

For their contribution to the film’s feeling of events unfolding, rather than being staged, Blake and Glascock were nominated for a Motion Picture Sound Editors’ Golden Reel Award, as they would for their work on Erin Brockovich (2000) and Ocean’s Eleven (2001). “It was an amazing moment in that period, too, with Erin Brockovich, Traffic and Ocean’s Eleven being back to back,” Blake says. And Blake — along with the rest of Soderbergh’s trusty sound team — was along for that remarkable ride.

But Traffic stands apart, for confirming Blake’s confidence in mixing in Pro Tools, which allowed him to shift his work to his home turf. “It completely changed how I work,” Blake says. “And where I work.”