By Peter Tonguette

When Orson Welles was readying himself to begin making his first film — the film that would become arguably the greatest ever made, 1941’s “Citizen Kane” — he is said to have taken in 40-some screenings of John Ford’s 1939 masterpiece “Stagecoach.”

“I wanted to learn how to make movies, and that’s such a classically perfect one — don’t you think so?,” Welles said in his interview book with his friend and interlocutor Peter Bogdanovich, “This Is Orson Welles.” “Not by any means my favorite Ford, but what a textbook!”

When it comes to primers in the fundamentals of cinema, few films can top “Stagecoach” or, for that matter, “Citizen Kane.” But, without overstating my case, I have always felt that it might be almost as instructive to take a crash course in the films of Bogdanovich himself: “The Last Picture Show” (1971), “Paper Moon” (1973), “Saint Jack” (1979), and so many others. Bogdanovich died on January 6 at the age of 82.

Of course, Bogdanovich, also a widely respected film scholar, would be the first to say that his films didn’t contribute in a fundamental way to film grammar; he came along decades after the earliest pioneers had hung up their spurs.

Yet, if Bogdanovich was not an innovator, he was surely a brilliant expositor of the classical style — especially the ineffable art of montage. His films are full of bravura displays of editing: In “The Last Picture Show,” edited by Donn Cambern, ACE, a confrontation between adolescent pals Duane Jackson (Jeff Bridges) and Sonny Crawford (Timothy Bottoms) over their mutual affection for Jacy Farrow (Cybill Shepherd) is expressed in a barrage of quickly alternating extreme close-ups, culminating with Duane striking Sonny with a bottle of beer — it’s a bit like a teenage drama reimagined by Eisenstein. The famous dissolve at the end of the film — slowly transitioning from a receding dolly shot of Sonny and Ruth Popper (Cloris Leachman) to a pan showing the shuttered Royal Theatre — is one of many such long, evocative dissolves in Bogdanovich’s films.

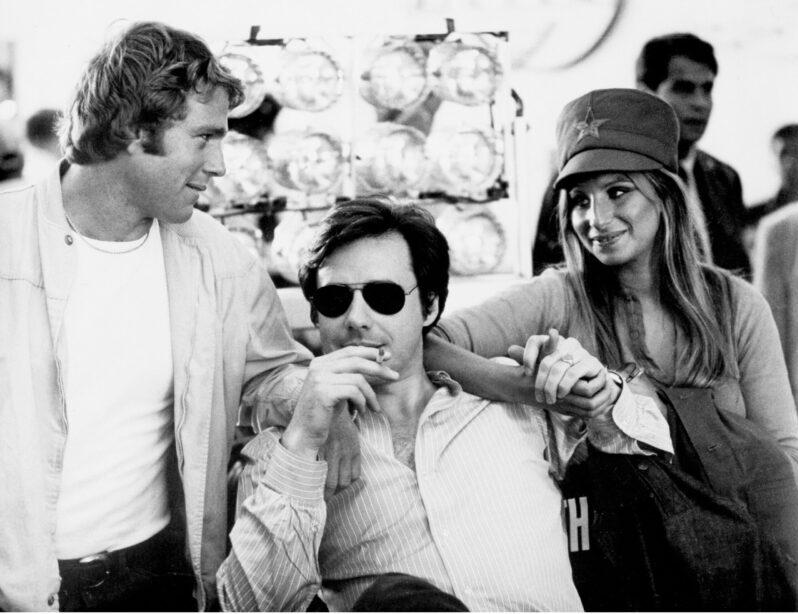

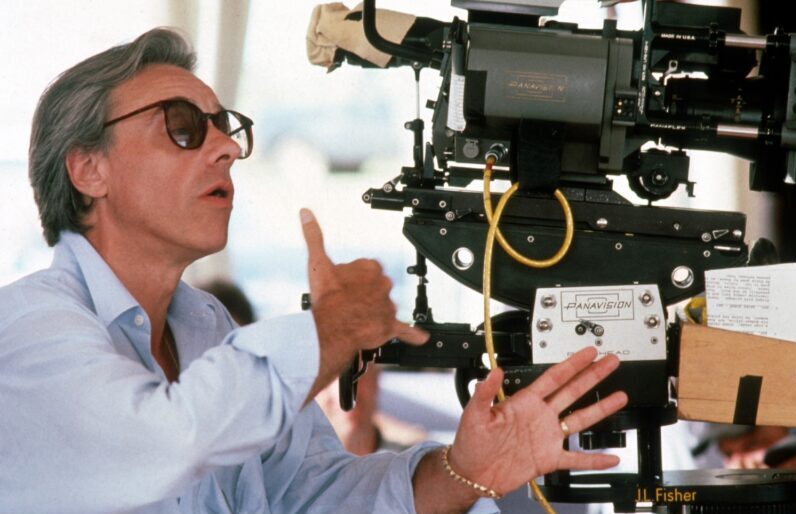

Peter Bogdanovich directing “Texasville.” PHOTO: Columbia Pictures/Photofest.

Above all, Bogdanovich’s films are distinguished by an unwavering commitment to the close-up combined with the point-of-view shot, which allows us, through the marrying of the two angles in editing, to inhabit his characters’ minds — to see what they’re seeing.

During her short stint reviewing films for The New York Times, the great essayist and critic Renata Adler wrote appreciatively of Bogdanovich’s debut film, 1968’s “Targets,” which revolves, in part, around a coolly maniacal Vietnam War veteran-turned-serial killer, Bobby (Tim O’Kelly). Adler, who called Bogdanovich “an expert on the silent film,” noted the way the camera and cutting put us in the mind of Bobby, from whose perspective we see his killings — a brilliant effect that, in the context of “Targets,” is also a bit troubling. “That is the extraordinary thing: the perspective of the film is almost entirely the perspective of the gun,” Adler wrote in The New York Times, adding, “The audience in ‘Targets’ becomes the sniper, except for the impulse and infinitesimal action of pulling the trigger — and these exceptions are felt as a definite lack.”

Bogdanovich seldom returned to material as grim as “Targets,” and in his later films, close-ups and point-of-view shots more often allowed us to experience a characters’ love or longing. Sometimes, whole scenes in his films seem to exist just to provide an excuse for a little moment between the characters. In his touching true-life story “Mask” (1985), edited by Eva Gardos and John Ford’s daughter, Barbara Ford, there’s an exchange of close-ups when the physically deformed protagonist Rocky Dennis (Eric Stoltz) spots in the distance his pretty classmate Lisa (Alexandra Powers), who mouths the words “Have a great summer.”

Other examples abound. In his brilliant screen farce “Noises Off” (1992), edited by Lisa Day primarily in long, flowing takes, there’s the quickest exchange of close-ups between at-his-wit’s-end theater director Lloyd Fellowes (Michael Caine) and his leading lady (and inamorata) Brooke Ashton (Nicollette Sheridan), at whom he rather devilishly winks. And in “The Cat’s Meow” (2001), his dazzling account of a murder aboard William Randolph Hearst’s yacht edited by Edward Norris, there’s an ambiguous series of close-ups between Marion Davies (Kirsten Dunst), looking through a porthole on her lover Hearst’s vessel, and Charlie Chaplin (Eddie Izzard), standing on the dock; in shots that shift from her perspective to his, and back again, their expressions tell us everything.

This is also basic film grammar, but few modern directors use that grammar as impressively or intuitively—and few were as appreciative of what cutting could do. For about 18 years, I was fortunate to interview Peter for what became a book on his life and work, “Picturing Peter Bogdanovich: My Conversations with the New Hollywood Director.” He was also a friend. Over the course of our conversations, the theme of editing came up again and again.

In the mid-1960s, Bogdanovich, then a features writer for Esquire and other magazines, latched onto the Roger Corman B-movie caravan. As Corman’s assistant on the biker film “The Wild Angels” (1966), starring Peter Fonda and Nancy Sinatra, Bogdanovich not only rewrote, by his account, 80 percent of the script but also directed three weeks’ worth of second-unit footage. When it came time to cut those scenes into the film, Bogdanovich told me, Monte Hellman — an acclaimed director then working as an editor for Corman — called the boss to say that the footage wasn’t coming together.

“So I went down and looked at it, and, of course, it was cut all wrong,” Bogdanovich said, adding that, when he explained the situation to Corman, the producer-director told him to cut the scenes himself. After learning how to use the Moviola, Bogdanovich said, he edited the material he shot himself. “I learned to edit in my head before I even shot it,” Bogdanovich said. “All of the great directors I talked to — Ford and Hawks and Orson and Dwan — they all cut in the camera.”

This didn’t mean the postproduction process was rendered superfluous, but simply that Bogdanovich, like those Golden Age directors as well as later filmmakers such as Sidney Lumet, had a notion of how his shots should go together before he called “action.” On “What’s Up, Doc?,” Bogdanovich inaugurated a multi-film collaboration with Oscar-winning picture editor Verna Fields, who had been the sound editor on “Targets.” Even so, Bogdanovich told me that he still physically marked cuts on the film. “‘S’ means start — leave that frame in,” he said. “‘C’ means cut — cut that frame out. That’s how we did the whole picture.”

In a recent interview with CineMontage, picture editor Scott Vickrey, ACE — who worked with Bogdanovich on the romantic comedy “They All Laughed” (1981) and on his made-for-television biopic “The Mystery of Natalie Wood” (2004) — confirmed that Bogdanovich was still “marking the film” when they first worked together.

“I’d never seen anyone do that, and I had assisted on films directed by Alan Pakula and Mike Nichols, but since it was my first gig as an editor, I let it go,” Vickrey said. “He definitely liked to call all the shots, or should I say cuts, but if you were industrious, you could do stuff on your own and show it to him and, if you presented it to him with enthusiasm and a good defense, he would laugh and say, ‘OK, Scott,’ but not all the time.”

But Bogdanovich really did see the film ahead of time, Vickrey said.

“He did know how it was going to go together. Sometimes it was amazing, especially on ‘They All Laughed,’” Vickrey said. “The very beginning of the film is 10 minutes long and it’s all about looks and POVs. I remember putting together the scene, and then he came into the editing room, which was actually an adjoining room at the Plaza Hotel, and he said, ‘Almost but not quite,’ and showed me how he really wanted it to go together and it made perfect sense.”

When Vickrey worked with Bogdanovich decades later, on the Natalie Wood biopic, the director had loosened up considerably, he said.

“It was a whole different ballgame,” Vickrey said. “Peter had mellowed, and I had become much more confident. There was no marking of film and the project moved along much more smoothly. We had a good time together.”

But what never changed was Bogdanovich’s belief in the intrinsic power of each shot and therefore each cut.

“The most basic thing in my approach to movies is that each shot has to be a building block,” Bogdanovich once told me. “If you can make it do double duty — do more than one thing — all the better. Each shot has its own meaning. It’s not just functional.”