by Mel Lambert

To relate the history of film post- production sound during the past 75 years is to tell the story of the creative post facilities that made such developments possible through a combination of tenacity and technical developments.

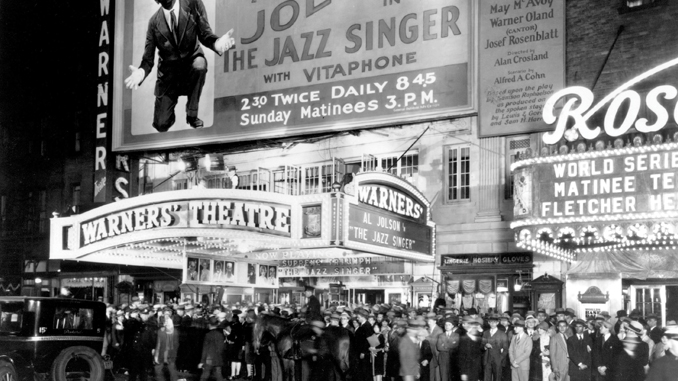

It is widely recognized that Warner Bros.’ The Jazz Singer, which premiered October 6, 1927, heralded the modern sound era, with the accompanying audio track being played back from phonographs linked mechanically to the projector. While synchronizing sound and picture using Warner’s Vitaphone system was problematic, to say the least, the project was a huge success. Made as a silent film (it has been reported that Harry and Jack Warner, like most Hollywood producers at the time, did not favor talking pictures), The Jazz Singer was intended to be accompanied by a pre-recorded musical score, plus several synchronized songs sung by its star Al Jolson.

The Jazz Singer opened in 1927.

Warner Bros.

Still, there were naysayers. Legendary film director D.W. Griffith stated, “We don’t want, and never shall, the human voice in our movies,” while British documentary filmmaker Paul Rotha offered, “A film in which the speech and sound effects are perfectly synchronized and coincide with their visual image is absolutely contrary to the aims of cinema. It is a degenerate and misguided attempt to destroy the use of film.”

In reaction to the demand created for the new Vitaphone sound-on-disc offerings, Warner Bros. probably was one of the first studios to initiate a post- production department where soundtracks could be prepared and mastered in quantity. Disc recorders were soon joined by specialist cameras that recorded a modulated sound image on film — the major advantage being that the two elements could be synchronized via a conventional, sprocket-based interlock.

Capitalizing upon innovations made in Germany during the 1930s, audio engineer Jack Mullin — as a member of the US Army Signal Corps during World War II — acquired a pair of Magnetophon reel-to-reel machines and recording tape from a German radio station in 1945. For several years, Mullin worked to develop the machines for commercial use, including soundtrack recording. In 1947, he demonstrated his systems at MGM Studios in Hollywood. Both quarter-inch tape and mag-coated 35mm film were to offer enormous creative opportunities for Hollywood sound departments — the former for acquiring production sound and sound effects on location using portable machines, and the latter to ensure accurate sprocket synchronization with projected film during editorial and re-recording.

Within modern technology, Dolby Laboratories enabled stereo recordings on 35mm release prints using an analogue SVA format — first in 1974 with A-type, then again in 1987 with SR noise reduction. During the 1990s, DTS, Sony and Dolby introduced digital multi-channel sound. According to Ioan Allen, senior vice president at Dolby Laboratories, “The first married soundtrack was made in 1909 by Frenchman Eugene Lauste, who worked with both variable-area and variable- density soundtracks. The playback of variable-area photographic soundtracks today is still based, essentially, on the techniques used by Lauste over 100 years ago.”

Audio pioneer Alan Blumlein developed the first stereo photographic track in 1933, while the first film commercially released with a stereo optical soundtrack was Walt Disney Company’s Fantasia in 1940. “Fantasound” was a double-system process, with the soundtrack interlocked on a separate 35mm film; a single control track adjusted the gain of three independent audio channels.

Sound technicians in 1941 listen through earphones to the music of Fantasia piped in from the orchestra stage on the floor above, and soften or increase the volume of recording according to individual scores for separate sections of the orchestra.

With emergent technologies enabling creative sound editorial and re-recording, film studios and forward- thinking entrepreneurs began to develop sound-focused facilities. For historical reasons — and because of its high concentration of film studios — the majorities of such operations were based in Los Angeles, although New York offered a range of competitive facilities (which will be featured in a subsequent issue of CineMontage). This article will attempt to touch on some of the major facilities, although there are too many to include them all.

THE MODERN ERA

Within the Hollywood community, Loren L. Ryder (later to found Ryder Sound Services, widely considered to be the West Coast’s first independent sound facility) soon recognized the creative potential of magnetic over optical recording. Optical recorders were cumbersome and difficult to move from location to location; reportedly, Ryder transported his system in an 11-ton truck.

Following the import of the first Swiss-built Nagra III portable recorders in 1961, magnetic recording was first used in 1962 on the United Artists’ film Geronimo and subsequently on several TV shows. As sound director and chief engineer at Paramount Studios, Ryder was awarded five Academy Awards and nominated for 12 during his career. For more than two decades, he served as head of sound on a number of landmark films, including Double Indemnity (1944), The War of the Worlds (1953), Rear Window (1954) and The Ten Commandments (1956). When Ryder retired in 1976, he sold his company to re-recording mixer Leo Chaloukian, who started at Ryder Sound Services in 1955. The company was sold to Soundelux Entertainment in 1997, and Chaloukian became the company’s senior vice president.

SOUNDELUX

Co-founded in 1982 by award-winning industry veterans Lon Bender and Wylie Stateman, Soundelux quickly earned an enviable reputation as an independent facility where emerging technologies and creative techniques were developed, including sound design and editorial using digital audio workstations. Bender and Stateman, along with a team of talented supervising sound editors, designers and mixers, continue to reinforce the company’s “essence of creative curiosity, a drive for innovation and sensitivity to the unique needs of film directors.”

In 2000, Liberty Media Group (LMG) acquired Soundelux, with LMG soon being renamed Ascent Media Group, Creative Sound Services. Nine years later, the post- production group became a division of Discovery Communications — CSS Studios — that currently comprises Todd-AO (which opened in 1953 as a joint venture between producer/director Mike Todd and American Optical Company), Soundelux, Modern Music and The Hollywood Edge in Los Angeles, plus Sound One in New York. Glen Glenn Sound, which opened in Hollywood in 1936, was acquired by Todd-AO in 1986. (At press time, it was announced that CSS Studios has been acquired by Empire Investment Holdings.)

In old Arizona (1928) was the first movie to contain scenes with synchronized sound that had been recorded on location.

Fox Film Corp

FOX FILM CORP./20TH CENTURY-FOX STUDIOS

Fox Film Corporation was also an early innovator in sound, having production facilities in Hollywood since 1916, and West Los Angeles a decade later. Currently, as 20th Century Fox (since 1935), it operates three re-recording stages, plus Foley, ADR and scoring stages. According to Fox Studios’ Robert Kizer, “The studio’s involvement with sound-on-film dates back to the late 1920s, with a process known as Movietone. Fox and Warner Bros. agreed to have theatres equipped to run both Movietone and Vitaphone sound processes. Back in the pre-magnetic tape era, our music department used 200-mil optical tracks for added fidelity, and mixed the use of variable-area and variable- density optical tracks to get more volume or enhanced clarity for music.”

The first Fox Newsreel with synchronized sound was screened at the Roxy Theatre in New York in April 1927. “By the middle of the following year, Paramount, Universal and MGM signed up for Movietone, with construction beginning on Movietone City, reportedly the first movie studio facility completely designed for sound-on-film movie production,” Kizer continues. Movietone City is now the current 20th Century Fox studio complex. Fox’s In Old Arizona (1928) was the first movie to contain scenes with synchronized sound that had been recorded on location. By 1936, Warner Bros. had abandoned Vitaphone, at which time Movietone and the rival RCA Photophone process became the standard sound-on-film systems for theatrical exhibition.

Says Kizer, “Probably the biggest achievement in the modern era was the Dolby Stereo matrix optical soundtrack,” introduced in 1976 for A Star is Born, and finding popular success with Star Wars. Following the introduction in 1952 of Cinerama, which used an interlocked 35mm mag reel carrying seven audio channels, Fox developed CinemaScope with four-channel magnetic analogue sound in a left/center/right/surround configuration. (Dolby Laboratories adopted that same layout when it introduced its SVA optical tracks.)

Summarizing what he considers the top five technical developments of sound, Jeff Minnich, vice president of engineering, post-production, at 20th Century Fox, says, “Movietone sound-on-film, followed by the Fox Post-Production Center with fully digital re-recording workflows; our custom-designed, digitally controlled analogue ADR and monitoring systems; fully integrated, network-based workflows to record, edit, mix, master and archive sound; and a lot-wide network architecture for file-based delivery to our customers from capture, process, finish and delivery.” Just around the technology corner, according to Minnich, is a fully automated, digital vault system for all Fox theatrical and TV finished assets.

Don Rogers.

GOLDWYN STUDIOS

Although he began his career within Todd-AO’s picture department in 1970, Don Rogers joined Goldwyn Studios’ Sawyer Facility, which at the time comprised two dub stages, a Foley/ADR stage and editorial suites. “We rapidly expanded the facility, adding more stages and editorial support as the film industry embraced multi-channel sound,” Rogers recalls. The Goldwyn facility was purchased by Warner Bros. in 1979 for a reported $35.5 million, after which Rogers oversaw refurbishment of The Burbank Studios (TBS) to create a number of re-recording stages and sound-editorial suites.

In terms of landmark technical developments, according to Rogers, “The availability of three- and six-track 35mm mag let us dub Raiders of the Lost Ark [1981] to six-track at Goldwyn. We also added two sound units for striping 70mm prints, with a quality-control department. Star Wars, for example, required some 200 70mm release prints. Harrison and Neve consoles with Flying Faders let us handle big movies with up to as many as 100 sound effects tracks that could be re-recorded with full-level automation. And Pro Tools workstations for mixing and editing were a major innovation, with random access to recorded material.”

Rogers has a similar list of sound innovations: “First, ADR, using our RCA- built systems introduced in 1972, and which could cue picture and automation. Second, Flying Faders automation for our re-recording consoles, followed by Dolby Stereo, Dolby Digital and SDDS, which brought multi-channel sound to theatre audiences, noise reduction and de-essers, and Pro Tools workstations for enhanced creativity.”

WARNER BROS. STUDIO FACILITIES

As mentioned above, Warner Bros.’ connection dates back to the phonograph- based Vitaphone process. “Sound editors were able to edit on disc using synchronized turntables,” says Kim Waugh, senior vice president of post-production services at Warner Bros. Studio Facilities, who joined the operation in 2004 from Soundelux.

Warner Bros.’ Mixing Stage machine room in the late 1950s. Warner Bros.

“We were early adopters of optical recorders and then mag-based systems when they became available from RCA and MagnaTech [in the 1950s],” adds Kevin Collier, Warner’s director of video operations. Wall adds, “We were also early adopters of digital audio, starting with NED Synclavier systems and then AMS Audiophile workstations.” “We also used Digital Audio Research systems and then Fairlight and Waveframe editing systems,” interjects Collier. “Today, we are using Pro Tools exclusively for sound editorial and mixing, with a choice of DAW-based control surfaces as well as traditional digital consoles for re-recording. For maximum flexibility, our Stage 12 features a hybrid of AMS Neve DFC and Avid ICON control surfaces in a unique console frame design that lets us reconfigure the system to accommodate a filmmaker’s mixing preferences.”

Waugh’s top five technical developments: “The 1926 introduction of our Vitaphone process; the advent in 1933 of central machine rooms that house multiple recording and playback turntables; optical recording; magnetic recording; and digital workstations that enable comprehensive ‘mixing inside the box.’” In terms of future developments, the new Warner Bros. Studios Leavesden production facility opened recently in North London, England. The studio is also actively seeking a post presence in the British capital, and plans to open a co- ventured sound editorial facility in New York during December 2012.

UNIVERSAL STUDIOS SOUND

Universal Studios also operates a number of dub stages and editorial suites at its 400-acre lot in Universal City, and this year is celebrating its centennial. According to David “Doc” Goldstein, the post facility’s vice president, post- production engineering, who joined the company in 1985 from the Goldwyn Sound Department at Warner Hollywood Studios, “The wide-scale use of multi-track tape machines linked via time code to a 35mm mag dubber [locked to picture] let us add more tracks to the mix. That technology dates back to 1980, and was used to great effect for The Jazz Singer [1980] with Neil Diamond, where four 24-track machines were locked to picture for playback.

Universal Studios Sound, circa 1940. Universal Studios

“We also used Sony PCM-3324 digital multi-track machines while re-recording Stop Making Sense in Room A at Goldwyn in 1984,” Goldstein continues. “Working with Bill Varney at Universal — which he joined from Goldwyn in 1985 — we developed a tape-based workflow, transitioning from analogue to digital with the Tascam DA-88 eight-track machines. We purchased around 50 Tascam DA-88s for playback and recording on all our dub stages — they were very successful — and then used later-generation Tascam MMP- 16 16-track playback and MMR-8 eight- track, disc-based recorders with outboard Apogee converters.”

Universal first started using Digital Audio Research Soundstation workstations for dialogue editing in the early 1990s, and then switched to Pro Tools as its workstation of choice, according to Goldstein. “Later, Digidesign added features that we needed — including destructive editing and punch-in so that the system behaved like familiar dubbers,” he adds. “Avid’s Tom Graham helped us make the transition to Pro Tools 7 [in 2006-2007], which had the features we needed for film post-production. These days, we use a file-based workflow with storage- area networks interconnecting each of the rooms linked to a pair of 1 Petabyte LTO5- based backup systems.”

Goldstein cites his top three technical developments: “Foley recording, which was invented at Universal by Jack Foley; file-based workflows using SANs in a networked environment; and Remote Reviews, which, for a couple of years, has allowed directors to view works-in-progress using SohoNet and other connectivity.”

Sony Pictures’ Kim Novak Stage. Sony Pictures Studios

SONY PICTURES STUDIOS

The Sony Pictures Studios lot in Culver City was the original home for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and currently houses Sony’s Columbia and TriStar operations, including a number of historical dub stages and editorial suites. Until 1972, Columbia Pictures was located at Sunset-Gower Studios in Hollywood, having spent many years in Burbank, sharing TBS with Warner Bros. When Sony purchased Columbia from Coca-Cola in 1991, it was agreed that the latter would exit the TBS lot, which since then has been the sole provenance of Warner Bros., with the latter relocating to the Sony-owned, former MGM lot. According to Richard Branca, executive vice president, sound projection and video, who joined the operation in 1980, the current Sony Pictures Post- Production Facilities houses 10 film/TV mixing theatres, a scoring stage, DVD restoration/mastering suites, ADR/Foley stages and numerous editorial suites.

WALT DISNEY STUDIOS

Prior to opening its 110-acre Burbank lot in 1940, Walt Disney Studios was located at several different locations in Los Angeles and Hollywood. Originally designed around the animation process, the sound department was created by Jimmy MacDonald, whose inventive sound effects defined the classic Disney animated cartoon. (In 1946, MacDonald became the second voice of Mickey Mouse, after Walt Disney decided that it was time to pass the job onto someone he could trust with his beloved creation.) Disney owns several patents for networked, real-time sound- streaming technology, which were used for global voice recording and precedes today’s use of networks for ADR and other creative media collaboration.

Disney employees transport equipment onto the Sounds Effects Stage

in this scene from the 1941 film the reluctant dragon.

Disney

Currently, Disney is completing a Digital Studio Center that will form the hub of the studio’s file-based workflows, as well as housing a new picture and sound editorial center. The facility also features a pair of pre-dub/sound design rooms specifically designed for Dolby ATMOS. “Collaboration at the heart of filmmaking drove Disney’s latest innovation,” says general manager Leon Silverman. “The Global Collaboration Theater is connected to the studio’s multiple fiber connections, and features 4K projection.”

SKYWALKER SOUND

Of the independent post facilities based away from Hollywood, Skywalker Sound’s 155,000-square-foot Technical Building, which opened in Marin County north of San Francisco in 1987, includes six dub stages, sound editing rooms, a Foley/ ADR stage and a scoring stage; the complex also includes guest accommodations. Skywalker was an early pioneer of SoundDroid and EditDroid digital editing systems, and created the first bi-phase codec that enables long-distance sound and picture synchronization for remotely located filmmakers, in addition to APT WorldNet Skylink, jointly developed with APT.

The West Coast post-production community is based around a modest number of innovative facilities whose staff brings a unique blend of art and technology to the world’s leading filmmakers. And as long as that community continues to attract the very best creative talent, well versed in the art of sound editorial and re-recording, Hollywood’s dominance in sound will continue.