by Debra Kaufman • portraits by Gregory Schwartz

NBC’s American Ninja Warrior (2009-present), now celebrating its 10thseason with its May 30 premiere, is a monster success. The series features thousands of athletes/contestants from dozens of US cities, who compete for the title of American Ninja champion — if they can survive the final trial at the formidable Mount Midoriyama, a four-stage obstacle course in Las Vegas.

American Ninja Warrior.

NBCUniversal

Even viewers who don’t watch sports or reality TV are glued to the show, which is a singular blend of both genres. Any way you look at it, ANW has soared far from its origins at now-defunct cable channel G4, on which it debuted in December 2009 as the qualifying tournament for Americans who wanted to participate in the Japanese competition Sasuke, a sports/entertainment TV special in that country.

Just as the show’s athletes face daunting deterrents in their quest for glory, so a top team of picture editors and assistants faces the taxing task of sifting through, keeping track of and organizing a crazy amount of footage to build a weekly two-hour show. When editor Mary DeChambres, ACE, joined the show some 18 months ago, she was impressed by the teamwork. “I don’t think I’ve ever worked with an assistant editing team as good as this one,” she says. “Our eight assistant editors ingest, group and organize the footage of 150 competitor runs per city — and we shoot in six cities per season, with as many as 28 cameras for each run. There are 14 editors on the show and it truly takes all of us to put together one two-hour episode.”

Mary DeChambres.

To understand the complexity of editing American Ninja Warrior, it helps to be familiar with what makes up a two-hour episode: the cold opens, hometown packages (also called pop-ins) and runs. The first is the segment that opens the show and introduces the city and its contestants. Following are the hometown packages, which tell the background stories of the competitors — with liberal use of their own video footage and photos. Finally, the runs are the competitions themselves, held on obstacle courses ringed with cameras.

“I put our editors up against anyone else,” says executive producer Brian Richardson. “What we do is unique in TV. We’re cutting a sporting event and these emotional background stories — two completely different styles of editing — and we churn out two hours every week. That’s a lot of TV, and maintaining the quality is a real accomplishment.”

“American Ninja Warrior is an extremely complicated show to edit,” fellow executive producer Anthony Storm adds. “It’s a large-scale primetime network extravaganza that’s a year-round operation. We’re constantly innovating. This season, we added a new graphic look, upgraded our music and continue to push the envelope with our hometown packages.” Storm stresses that the editors this season are also tasked with integrating a new set design featuring massive LED screens into the show. “Our challenge is that when you turn on a new episode, you know right away that it’s a new episode, that everything in Season 10 is clearly Season 10,” he says.

According to supervising producer Jon Provost, who is also a supervising editor, the show evolved, especially through Seasons 4 and 5, to become the “puzzle” it is today, mixing runs with home packages and cold opens. The team quickly learned to stagger when the editors started, as the production went to new cities and the footage piled up. Some of the editors — Provost, Nick Gagnon, Curtis Pierce, Corey Ziemniak — go back to Season 4, and their expertise is prized. With four day-shift assistant editors and four night-shift assistants for a total of 22 editors and assistant editors, Provost plays to each team member’s strength.

Curtis Pierce.

Jon Provost.

“We streamline who is best at what,” he says. “But they do get to do other things, because we don’t want people to burn out creatively or feel like they only do one thing over and over.” If there are two runs in an act, for example, two editors cut those, while two others cut the hometown packages, another cuts the tease and a sixth cuts a “fast-forward” recap to show a montage of the runs that aren’t covered in full. “Six people can put together a single act,” Provost explains, “so communication is key.”

Communication as well as collaboration are strongly encouraged and practiced on American Ninja Warrior. Provost stays in close touch with the showrunners regarding how the video is grouped on the Avid system — a tricky challenge since the show has over 20 cameras, and Avid only supports 18 in a group.

All day long, Provost says he walks in and out of editors’ bays, watching what they are cutting; other editors and assistants do the same. “There are thousands of ways to cut the runs,” he maintains. “Even though I have worked on the show for seven years, I still show every single one of my cuts to another editor to ask if there’s anything he or she would do. You never get things perfect on your own. There is no one hero on the team; it’s a team of heroes banding together to make a great show.”

Pierce cuts most of the cold opens. “It starts us off and gets us excited,” he offers. “It lets us know what town we’re in and who the characters are, introducing the faces and ideas we’ll be seeing.” A cold open, says Pierce, is between one-and-a-half and two minutes long and takes four days to get into shape. The process starts Monday, when Pierce receives a script from the executive producers and a song that will play behind it. The editor prints out the song’s lyrics and puts the song on a loop for 30 minutes. “I have a giant white board in my room and I brainstorm any ideas that come into my head,” he reveals.

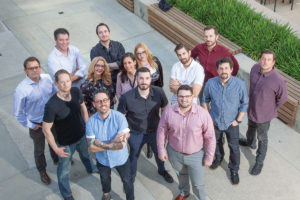

Ninja editors, from left, Tom Erwin, Jeff Bartsch, Kyle Barr (back), Curtis Pierce, Mary DeChambres, Michael Kalbron (back), Marcella Serrano, Nick Gagnon, Michelle Messina, Jon Provost, David Greene, Corey Ziemniak (back), Martin Singer and Scott Simmons.

Next, Pierce lays down the soundtrack, which is comprised of an announcer voiceover, competitors’ sound bites, the music and sound effects. That “radio edit” goes to the producer for comments, and then he and Storm go back and forth. Finding the visuals might seem like the easy part, but of course it isn’t. “You want an impactful moment, so finding that shot can take a long time,” concedes Pierce, noting that he has bins for previous season runs, submission videos, competitor video media selects and hometown videos from which to choose. The opens also change as the season progresses. The first episodes are character- and emotion-driven, according to Pierce, who adds, “When we get to the second set of the same cities, you’ll start to see footage from previous episodes and their home packages.”

Kyle Barr, along with a couple of other editors, cuts the hometown packages that give insight into each competitor. “It’s a little bit of their backstory, so the audience can have a personal connection with him or her,” he says. “These background packages make the ninja relatable — often they’re heart-warming stories.” Barr’s job begins when he gets several hours of footage, as well as a “string-out” — sound bites from people interviewed regarding the hometown, the competitor and anyone else relevant to the story, be they parents, co-workers or even other competitors.

American Ninja Warrior.

NBCUniversal

“I clean up the sound bites to make them sound better; then I go through all the footage to see what I have to work with,” he says. Like Pierce, Barr starts with the music. “For me, music is the foundation of the house I’m building,” he says. “That’s where you lead the audience to what emotion you want them to be feeling.” Once he has the cut with music and sounds bites, he begins filling it in with the competitor footage, photographs and B-roll. “It’s like putting a puzzle together, and each story is different, even if it’s the same kind of pieces,” says Barr, who says he produces several hometown packages per week. “It can be a grind, but you always have a feeling of accomplishment at the end.”

Co-supervising editor Gagnon, who has worked on the most episodes of ANW (72 through Season 9) going back to 2012, focuses on the runs or live elements of the show. Although the show is taped, the mandate is to make the competitions look and feel like live sporting events. “Most people don’t realize the extent of editing that goes into creating that feeling,” he explains. “We are truly creating an experience. That means no jump cuts, for example. Every editorial decision has to be calculated. Nothing is used by accident.”

Kyle Barr.

Nick Gagnon.

The result, says Gagnon, is that, in his opinion, the show “is closer to Major League Baseball than to The Voice.” The runs are then married with the story packages, and the work to build each episode’s 11 acts begins. “Our show is extremely compartmentalized but needs to feel like one seamless live event,” he continues. “The stories weave in and out and need to track and flow for two hours.”

It’s no surprise that ANW requires a night shift. Night lead assistant editor Alejandro Hurtado, who has been with the show since Season 6, and three other editors have a variety of tasks. “I never go in with expectations,” he contends. “When they’re working on the first episode, say, and it goes through a first cut, a fine cut and a locked cut, editors build it by acts. At the end of the day, we string it out together as a show build that gets sent out to the executive producers and the network. We’re the final stop that puts it all together.”

The night crew is also the first to ingest new footage into the system. “We grab the proxies from the XDCAM, and then we start logging the clips,” explains Hurtado. “One shift can ingest and log nine- to ten-hour shoots, times an average of 20 cameras, because auto-ingest grabs the proxies very quickly. For logging it, we have a run notes sheet with time code.” Most challenging, he says, is the grouping of all the clips: “We are organizing the groups, B-roll and competitor interviews for the editors, or they’d spend hours searching for things. We also split up groups by the hour and sub-group for each individual in the run.”

Transcoding, organizing and storing this massive amount of data is the job of lead assistant editor Matt Parcone, who’s in charge of workflow. He is tasked not only with storing the masters, but all the raw footage that didn’t make it into the master. “On any other show, if it didn’t air, it doesn’t exist,” he says. “That is not the case on our show. We are shooting with up to 28 cameras, so we’re referencing mountains of footage that needs to be available at a moment’s notice.”

Ninja assistant editors, from left, Kenley Kidd, Paul McDade, Craig Eustis, Steven Ty, Matt Parcone, Jamieson McGonigle, Alejandro Hurtado and Don Williams.

Parcone devised an Avid ISIS-based storage system that divides up the types of footage for which an editor might search. “Our hometown packages get written to a drive that stays on our main server,” he explains. “The external system I created lets us plug in certain drives to retrieve material from past seasons.” Parcone, who has been on the show since Season 6, relies on his expertise to determine where footage from the current show should reside. “I’m already looking to Seasons 11 and 12, although we’re on Season 10,” he adds. “I have to get my team to think a little more into the future and plan where the footage should be stored before it gets ingested.”

New this season is footage from 10-bit cameras. “We run most of it through Blackmagic Design’s DaVinci Resolve to apply LUTs, put that onto our RAW drives on the ISIS, and then transcode from there,” Parcone reveals. “We ordinarily would go to DNx145 but now we’re going to DNx220s when we up-rez because of the 10-bit.” The lead assistant also has to transcode footage from a wide range of cameras, including Canon Mark IIs, GoPros, a “Falcon Cam,” Sony XDCAM EX3s and lipstick cameras, as well as the high-speed footage from the Sony FS-700, which is used for slo-mo sequences. From the competitors, the team gets old home movies, phone videos and other footage with different frame rates and resolutions — all of which are transcoded into a high-resolution version via software.

Matt Parcone.

Alejandro Hurtado.

Parcone says the entire show has over 200 external 4tb drives to hold all the data at the ready, including all the media from approximately 600 contestants per season. “We have to keep all that media organized,” he states. All of the competitors and hometown packages are live on the ISIS; the runs go into the back-up process before they go into the library. Each season adds another 15 to 20 external drives to the library. “It’s a gigantic job,” he acknowledges, “and I try to keep my team working as fast as possible on our normal groupings and bringing in contestant media for the current system.”

Last season, a camera mistakenly recorded over some footage, but Parcone saved the day (it actually took three days) by recovering the footage from the camera’s FMU [Flash Memory Unit]. “But the craziness is not recovering footage,” he says. “It’s the strategic planning on which cameras to bring in first, what footage will get processed first, how you know what LUTs to use and which cameras need to go through Resolve. Then we transcode all of it. It sounds basic, but it can get quite convoluted. If a card gets misplaced, it throws a wrench into the workflow.”

Michelle Messina.

Editing ANW is such a specific process that not all editors click with it. Gagnon has seen it evolve through the years. Training new editors is one of the challenges. “We get some fantastic editors from big reality shows, and you can see them realize that this is not the same beast,” he explains. “It’s unlike any other show out there. It’s a slow process to ‘getting it.’”

He points to Michelle Messina, who joined American Ninja Warrior as an editor this season, cutting the runs, doing notes and helping get the shows together for the first pass. “I’ve done a plethora of unscripted reality for over a decade, but with Ninja, it’s been a while since I’ve felt so challenged,” she concedes. “There’s a right and wrong way to do every cut, and it’s been a little humbling to step back and re-adjust my workflow. However, this is a great team of people who are all helping each other constantly.”

Messina continues: “Working on Ninja is never cookie-cutter; every piece is created specifically to tell that person’s story. I enjoy combining the elements of a live sports show and a narrative. The amount of footage is always challenging, especially because the schedule is tight. You have to keep it moving but still deliver top quality.

“Ultimately,” she concludes, “it’s inspiring to work on such an uplifting show where all the editors are A-list and at the top of their game.”