By Lucy Donaldson

Last November, I attended an event organized by the Guild’s women’s steering committee to celebrate this year’s female Emmy nominees. The committee members and nominees numbered 40 in total. It was a great get-together, and it was heartening to see how many women are editing award-worthy shows.

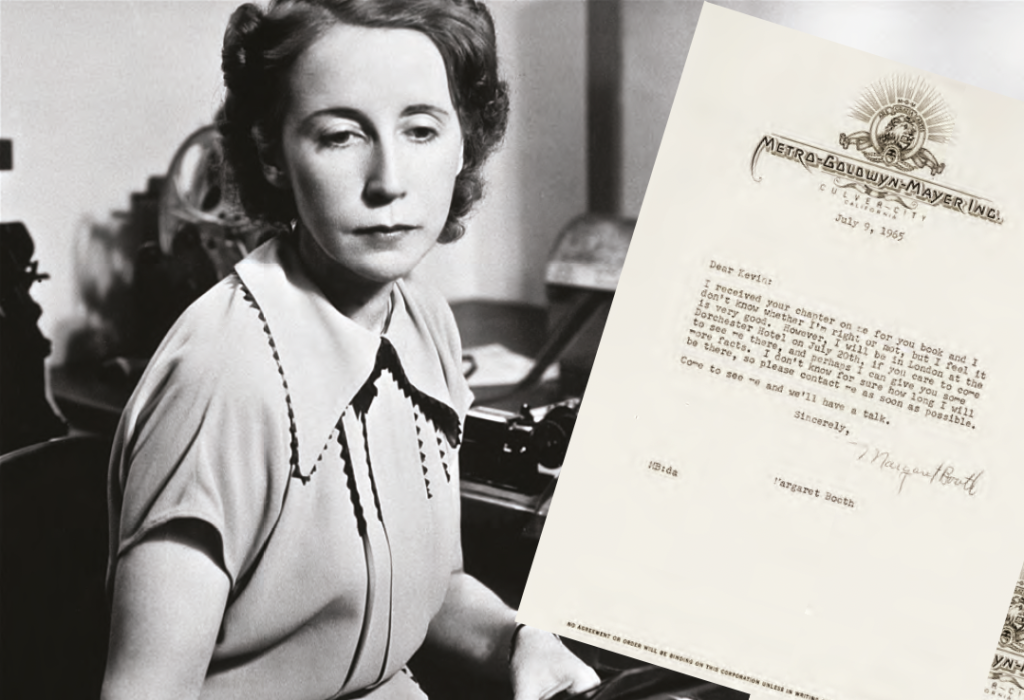

BOSS: Margaret Booth, above, ruled post-production at MGM with an iron fist, with the 1965 letter below capturing her cool style.

That got me thinking about some research I did more than 14 years ago, when I was studying for my M.A. at the National Film and Television School in the U.K. The resulting paper was eventually called “Matriarchs and Moviolas: Women in the Cutting Rooms of Early Hollywood.” The spark was the excellent documentary “Cutting Edge: The Magic of Movie Editing” by Wendy Apple. The story of these pioneering women captured my imagination and inspired me at the start of my career — and it might inspire others, too.

After some initial research, I found there was a small group of women who had exceptionally successful editing careers that started almost at the birth of cinema and continued for much of the 20th century. However, according to a 1945 Los Angeles Times article, out of about 300 working editors in Hollywood, only eight were women. How did this group get started and why were they so outnumbered?

In the early days, cutting, patching (gluing trims together), sorting and tinting were seen as functional rather than creative or technical roles, and since women were the cheapest available labor, they were the most likely candidates to fulfill them. Ironically, the fact that these women were doing a job that was perceived as irrelevant gave them a foothold on what would turn out to be a key role in the filmmaking process.

As the role evolved, so did the skills of the women doing it. As Ally Acker points out in her book “Reel Women,” “by the time filmmakers began to discover that film could be arranged, shuffled, and cut in ways that would make the final effect much more powerful for an audience, women were technical masters.”

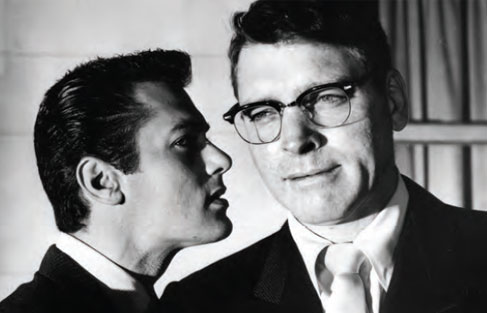

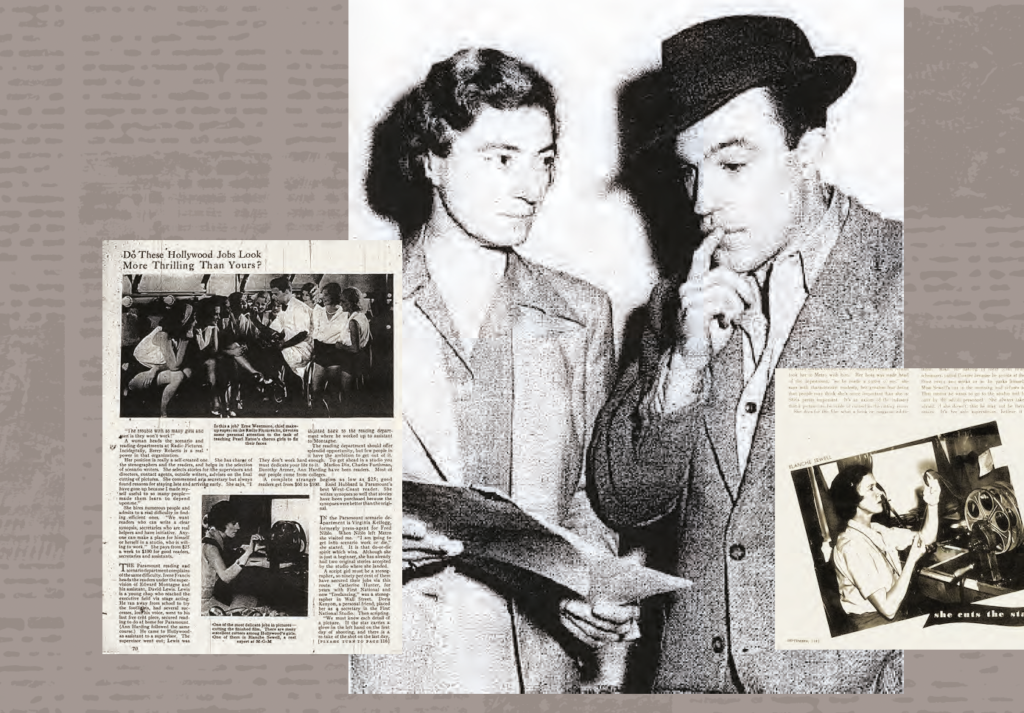

ONE FRAME AT A TIME: Anne Bauchens followed Cecil B. DeMille to Hollywood. Right inset, Barbara McLean watches dailies with Darryl Zanuck.

Left inset, a magazine interview with editor Alma Macrorie.

To find out more about these remarkable women, I searched for recorded evidence of female editors working in Hollywood between 1900 and 1940. Here I came up with a surprisingly short list of 11 names, all belonging to women who had very significant editing careers: Anne Bauchens, Margaret Booth, Adrienne Fazan, Viola Lawrence, Alma Macrorie, Barbara McLean, Irene Morra, Blanche Sewell, Rose Smith, Dorothy Spencer and Eda Warren. Other names cropped up in my research: Dorothy Arzner accumulated a handful of editing credits before turning to directing; Patricia Rooney, Madge Tyrone, Mildred Rich and Helen Lewis edited a number of films but their careers petered out after a few years. Undoubtedly, there must have been others lost to recorded history.

Of the 11, I decided to concentrate on four (based largely on availability of information): Margaret Booth (“Camille,” “Mutiny on the Bounty”), Barbara McLean (“All About Eve,” “Wilson,” “Alexander’sRagtime Band”), Adrienne Fazan (“Singin’ in the Rain,” “An American in Paris”) and Anne Bauchens (“The Ten Commandments,” “The Greatest Show on Earth”).

All of these women were gifted artists who were at the right place at the right time. They seem extremely hard-working, dedicating their lives to the studios, seemingly for the joy of doing a good job, whether or not they got their due from their employers. They cultivated strong key relationships with powerful figures within the studio system and displayed a lot of loyalty, resulting in some extraordinarily long-lasting working relationships. They seemed perceptive about the moods and whimsies of directors and producers, possessing what today would probably be called emotional intelligence: knowing how to handle delicate situations. And lastly, they were as tough as old boots, giving as good as they got when challenged and demanding respect from those around them.

SHOP TALK: Adrienne Fazan confers with “American in Paris” star Gene Kelly.

Their stories might hold some lessons for us today.

MARGARET BOOTH (1898–2002)

Margaret Booth began working with D.W. Griffith in 1915 and was the supervising editor for MGM for more than 30 years, supervising up to 50 films a year. Her loyalty to the studio and her discretion were legendary. Film historian Kevin Brownlow described her in later life as having the manner of an expensive doctor: “Time with her was short and you were grateful for it.” Despite her reputation, she was nominated for just one Oscar for “Mutiny on the Bounty” (1936) (she didn’t win). But she eventually received a Special Academy Award in 1977 after 62 years in the industry.

After her stint with Griffith, Margaret Booth joined Louis B. Mayer’s studio where she came into direct contact with the director John Stahl and later, after the merger with Metro and Goldwyn, Irving Thalberg (“the greatest man who ever was in pictures”). She credited Stahl as being the person who taught her to cut.

She was undoubtedly tough, as she was tapped by Thalberg to work with director Erich Von Stroheim, the intemperate director who had, unsurprisingly, a lot of problems working with editors.

The technology of the time was rudimentary. In the early days, editors cut using negative prints since the labs that generated the positive prints hadn’t yet moved out West. Before the introduction of the Moviola in 1924, the cutters cut by hand, without key numbers.

“We just looked at it and matched the print with the negative,” she later said. “We had no numbers at all — we matched the action…. When I cut silent films, I used to count to myself … to get the rhythm.”

She thrived under Thalberg but declined his offer to make her a director, saying that she would rather be an editor. After Thalberg’s death, Mayer asked her to be supervising editor and to let him know immediately if she saw anything wrong with the pictures under her jurisdiction, particularly concerning how the stars were photographed.

It wasn’t always smooth sailing. Booth later described how she was bullied by Al Lewin, the associate producer on “Mutiny on the Bounty” (1935), who accused her of not using the best material. But she had formidable allies, including Thalberg.

Margaret was on the front line when sound technology came in. She admitted to it being “a period you just suffered through.” Frustrated by the process while working on MGM’s first sound picture, “Broadway Melody” (1929), she threw up her hands shouting: “If it’s not in sync I’ll kill myself!”

“I believe like writing, good cutting cannot be analyzed,” Booth once said. “It is intangible, like all branches of showmanship or artistry. Instinctively you know whether or not a scene is coming out right. If it is not, there is no way to patch it up. There is nothing to do but start from the beginning.”

ANNE BAUCHENS (1882–1967)

Anne Bauchens is credited with many firsts: She was the first woman editor to win an Oscar (for “Northwest Mounted Police” in 1940; she ended up winning three in total), the first person to start a secretarial department in Hollywood, and was apparently the inventor of the role of script girl.

Like many women in early Hollywood, Bauchens started her career with a typewriter. She came to New York from St. Louis to try to find work as an actress. She ended up working as an assistant for William DeMille, the New York playwright. But Anne’s future would be most closely linked with William’s brother, Cecil B. DeMille.

When Cecil packed off to Hollywood, Anne (and William) followed him. So began a collaborative partnership between Anne and Cecil spanning 40 years and 42 films. De Mille insisted on Bauchens cutting all his films.

Their relationship seemed to be extraordinarily close and affectionate, eventually joking about mutual hearing loss and other signs of aging. But there was no romantic element to the relationship. A biographer recounts a story in which, after a near-collision, their car ended up with two wheels over a precipice. Bauchens threw her arms around De Mille’s neck and cried “Oh Cecil!” De Mille later said it was the only time in their relationship that he “roused her to passion.” (She never married; DeMille was married to the same woman for more than 50 years.)

It cannot have been easy being the editor for DeMille. For “The Ten Commandments” (1956), he shot 100,000 feet of film, which Bauchens had to reduce to 12,000. That translated into 16-hour work days during post.

But she earned the director’s gratitude, which he expressed in his own way. “There were times when, looking at certain completed scenes, I felt like running into the hills to hide,” he said in an interview, referring to their work relationship. “But

Annie says quietly, ‘Go up to the ranch for a few days, I’ll take care of this.’ And she always does.”

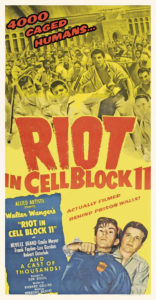

For ‘The Ten Commandments,’ Bauchens had to cut 100,000 feet of film to 12,000.

ADRIENNE FAZAN (1906–1986)

Fazan was the editor of the legendary musical “An American in Paris” (1951), but I suspect very little would be known about her had Donald Knox not written his 1972 book “The Magic Factory – How MGM Made ‘An American In Paris’.”

That book offers some candid insight into MGM and what it meant to work for the formidable Margaret Booth. Fazan worked until the latter part of her career almost exclusively for MGM, with filmmakers such as Vincente Minelli, Arthur Freed and Gene Kelly.

She was born in Germany to a French father and German mother, and had a varied early career. She got her break recutting talkies into silent films and then adding titles for movie theaters that had not yet installed sound equipment.

She then worked on MGM’s foreign-language films. At the time, the studio remade big pictures using foreign actors in four or five different languages. After this, she worked on shorts and documentaries for the studio and only broke into features during World War II, presumably when the studios lost many of their male editors to the armed forces.

“I would normally be assigned to a picture a few days before they began to turn cameras. The head of the editorial department would mostly come in and say, “Here’s a picture,” and throw a script at me. That’s how I first heard about ‘An American In Paris’,” she later said.

Fazan was, according to one writer, known for her “noisy disagreements” about projects and showed a marked impatience with studio rules. Rather than argue about overtime, she would work late into the night without pay. She was also outspoken about the wages at MGM and the studio’s pay structure. She was furious to discover that the top rate for editors was reserved for “relatives or favorite people” of studio boss Louis B. Mayer. “Mayer had THOUSANDS of relatives,” she later said, disgustedly. “Good God!”

The inequities remained even after she had won her two Oscars for “Singin’ in the Rain” (1952) and “Gigi” (1958).

Asked about Margaret Booth’s involvement on “An American in Paris,” Fazan replied: “None, thank God… Mr. Minnelli didn’t want her on the picture… [T]here were many directors who didn’t want her on their pictures, and there were some directors who couldn’t go to the toilet without her holding their hand.”

Fazan’s brittle relationship with Booth ended in 1964, when by her own account, she got into “quite a deal with Miss Booth… a real war.” According to Fazan, Booth reneged on a promise to let her edit a feature, then added insult to injury by offering her work “helping out on a TV show.” Fazan went “straight up through the roof” — and thus her 34 years at MGM came to an unpleasant end.

BARBARA MCLEAN (1903–1996)

Barbara “Bobbie” McLean in many ways could be seen as Margaret Booth’s opposite at Twentieth Century Fox.

She edited 62 out of her 64 films for Fox, and in 1960 she became the supervising editor there. However, she received more external recognition than Booth did, with seven Oscar nominations, including a win for “Wilson” in 1945, plus a Career Achievement Award in 1988.

She began her career in her father’s film laboratory and arrived in Hollywood in 1921. She worked at the Pickford Company, sharing elevators with silent film star Mary Pickford and enjoying what she later described as “a close-knit family” atmosphere at the studio.

McLean didn’t escape the torment of the era’s new technologies. In 1928, when she was working in the cutting department at First National on “Lilac Time,” music was being added to pictures by way of a disc playing in the theatre that was supposed to sync up with the action in the picture. “Every day when the picture opened we used to go over to Carthay Circle Theatre and try to get it in sync,” McLean later recalled. “Using a stopwatch and syncing the music crescendos to the airplane crashes, they would desperately try to get music and picture working together by adding a little more music or more length to the titles.”

McLean ended up doing some of the very earliest dialogue editing. Once, Mary Pickford had exclaimed on-camera about “these beautiful red roses” in a scene – although on black-and-white stock, the roses appeared white. McLean discreetly cut out the word “red.” “You’d think I’d performed a brain operation,” she later joked of the praise she received for the cut.

McLean forged strong alliances with powerful leaders, including an extremely close relationship with Fox boss Darryl F. Zanuck that in some ways resembled the ties between De Mille and Bauchens. “Studio executives knew that when Mr. Zanuck prefaced a statement with ‘Bobbie says…,’ he was not expressing an opinion but announcing a decision,” as one account put it. ■

Lucy Donaldson is a picture editor.