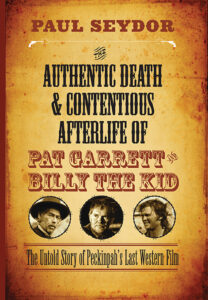

The Authentic Death & Contentious Afterlife of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid: The Untold Story of Peckinpah’s Last Western

by Paul Seydor, ACE

Northwestern University Press

Paperback, 408 pages, $29.95

ISBN 978-8101-3056-2

by Betsy A. McLane

Sometimes a title can be misleading, but in the case of The Authentic Death & Contentious Afterlife of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid: The Untold Story of Peckinpah’s Last Western — the title, including ampersand — is part and parcel of ACE member Paul Seydor’s exactingly told story. The notorious history of acclaimed director Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973); its decades-long gestation, multiple script versions, casting changes, troubled location shoot in the Mexican desert and, most controversially, its nightmarish post- production are detailed by Seydor in a way that is both excellent and excruciating.

The author is an expert not only on this film, Peckinpah and the Western genre, but on film editing. He is a working Guild editor and teaches the craft at the Dodge College of Film and Media Arts at Chapman University in Orange County, California. He authored Peckinpah: The Western Films – A Reconsideration (1997) and was nominated for an Oscar (with Nick Redman) as producer for Best Documentary Short for The Wild Bunch: An Album in Montage (1997), which Seydor also directed. These bona fides coupled with a 30-plus year devotion to the subject make this book an unequaled revelation of Peckinpah’s singular way of creating — and disowning — his art within the changing Hollywood studio system of the late 1960s and early ‘70s. These are the excellent and exciting elements in Authentic Death and Contentious Afterlife. The excruciating part is the challenge to get through this saga’s thousands of details, knowing that the outcome is a soul-draining collision of personalities and economic forces that make Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid a classic film maudit.

Seydor starts at the beginning of the “true” Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid story. Chapters One and Two are comprised of a thoroughly researched introduction to this mythic tale of the American West. The book is full of the same reliable scholarship, appended by almost 50 pages of notes, footnotes, bibliography and filmography. It also incorporates many unique interviews with Peckinpah’s collaborators, friends and antagonists conducted by the author. Brightest among these are the conversations with editor Roger Spottiswoode.

There is no one alive to interview about the Lincoln County, New Mexico cattle/business wars of the 1870s and ‘80s, which led to Garrett’s killing The Kid, so Seydor probes many recountings of this legend. He starts with “penny dreadfuls” published almost before Billy’s body was in the ground, and settles on the account written by (or as told to) Garrett as the most accurate. This is The Authentic Life of Billy – The Kid, the full title of which continues: “The Noted Desperado of the Southwest, Whose Deeds of Daring and Blood Made his Name a Terror in New Mexico, Arizona and Northern Mexico by Pat F. Garrett, Sheriff of Lincoln Co., New Mexico, by whom he was finally hunted down and captured by killing him, A Faithful and “Interesting Narrative” (inconsistent italics included).

There is no one alive to interview about the Lincoln County, New Mexico cattle/business wars of the 1870s and ‘80s, which led to Garrett’s killing The Kid, so Seydor probes many recountings of this legend. He starts with “penny dreadfuls” published almost before Billy’s body was in the ground, and settles on the account written by (or as told to) Garrett as the most accurate. This is The Authentic Life of Billy – The Kid, the full title of which continues: “The Noted Desperado of the Southwest, Whose Deeds of Daring and Blood Made his Name a Terror in New Mexico, Arizona and Northern Mexico by Pat F. Garrett, Sheriff of Lincoln Co., New Mexico, by whom he was finally hunted down and captured by killing him, A Faithful and “Interesting Narrative” (inconsistent italics included).

Respected novelist Charles Neider did a similar study for his fictionalization, The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones (1956), raising the story from pulp Western to serious novel. Study of this novel’s genesis and continuing influence comprises Seydor’s Chapter Three. Admired and adapted into a screenplay by Peckinpah in 1957 with Stanley Kubrick the intended director, Neider’s book and the screenplay are compared character-to-character and almost sequence-to- sequence in The Authentic Death. This screenplay never was filmed, but it eventually morphed into One Eyed Jacks (1961), starring and directed by Marlon Brando, and written by Guy Trosper. The original Peckinpah screenplay begins his long attachment to the Billy and Garrett material, and leads Seydor

to further detailed comparisons as he explores what became the shooting script for Pat Garret and Billy the Kid, written by Rudolph Wurlitzer and given to Peckinpah in 1970-71. Originally written for director Monte Hellman (whose Two Lane Blacktop was Wurlitzer’s first screenplay), this version was titled simply Billy the Kid and sold to producer Gordon Carroll at MGM.

From the moment Wurlitzer and Peckinpah began to work on the script and the film moved into pre-production with Carroll, there was trouble. Peckinpah was still shooting The Getaway (1972) and given that commitment and his ever-increasing alcoholism and erratic behavior, Billy the Kid received less than full attention. A nightmarish atmosphere was created by studio boss James Aubrey, a television executive who had no sympathy for film as art and was under pressure from MGM to produce big- name box office winners to generate quick cash for the studio’s new venture: the MGM Grand hotel casinos.

Peckinpah’s film was not the only one to suffer from this misguided policy, but Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid became the most notorious. Seydor offers details of the complicated casting (the studio wanted big name stars, but would not budget for them — even Brando got involved again for a while), equipment malfunction (a days’ worth of footage rendered useless because Aubrey would not authorize money for a camera tech, resulting in a cracked lens-mounting flange), debilitating flu that hit many of the cast and crew (including Peckinpah), and the sometimes violent clashes of personalities that characterized a Peckinpah shoot. He also chronicles the successes, such as the spectacular cinematography by John Coquillon and a consummate performance by James Coburn as Garrett.

The production sections of Seydor’s book are the least satisfying. What Authentic Death needs is a list of everyone involved: real people, the names their characters have in the novel, the various screenplays and the films; identification of the actors who played them, and the key crew members and executives. There are so many different names that the narrative becomes labyrinthian. The problem is made more acute by lack of an index. A good addition would be a chart like ones used to keep the names in War and Peace straight.

Understanding the book also demands knowledge of the film — and the Peckinpah mystique. Seydor appropriately refrains from repeating sordid rumors of the director’s behavior both on and off set, but many will not have heard those wild tales. This is especially frustrating when Seydor repeatedly mentions Peckinpah’s misogyny, but never provides a concrete example. Fortunately, the book creates a desire to watch more Peckinpah films and learn more about the man himself.

Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. MGM

Authentic Death is best in describing the tortuous post-production process. The schedule for post was reduced, and reduced again by trouble on the set, to only 13 weeks, with a first cut to be delivered one week after shooting ended. The picture editors were to be Bob Wolfe and Spottiswoode — the team that worked successfully on Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971) and The Getaway. For unknown reasons, Peckinpah replaced Wolfe with Gareth Craven, who at that point had edited only sound. Nastiness abounded among Aubrey, Peckinpah and Carroll, who fought for Peckinpah’s vision, but was under the thumb of the studio. Extra editors were hired and work went on around the clock.

Adding to the confusion was the fact that composer Jerry Fielding walked off the picture because he despised Bob Dylan’s song “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” playing over an important scene. Dylan, who also acted in Pat Garrett, had never worked on a score, but ended up as the default composer, with little input from Peckinpah, who felt loyal to Fielding. This left Spottiswoode in charge of every aspect of post, an impossible load. Peckinpah’s own behavior became more erratic. His contract allowed two previews of his director’s cut, but by the time that came around, his animosity toward Aubrey and (unjustly) Carroll, was so great that he did not even bother to attend the previews, a true slap in the face to the editors. Eventually, Peckinpah simply walked away from the film.

Spottiswoode — the white knight of the story — and team delivered a theatrical version, released with little success. Seydor devotes two chapters to dissecting the various “original” and reconstructed versions of the film. Here he excels; he is probably the only person who has seen every version available and he was key in creating the 2005 Special Edition DVD. He meticulously reviews each, even his own work, from a 2015 perspective. These chapters speak directly to readers who want to understand what editing can and cannot do. The comparisons offer extraordinary lessons in how material (good, bad and mediocre) can be edited in many ways to achieve various emotional, artistic and narrative results.

Seydor concludes with deft personal and professional opinions: “Ten Ways of Looking at an Unfinished Masterpiece and Its Director.” If anyone can speak authoritatively about Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, it is Paul Seydor. His knowledge illuminates a strange and fascinating story that should interest everyone who makes and loves films.