By Kevin Lewis

Where were you in ’62?” was the tagline for American Graffiti when it was released 39 years ago, in August 1973. It was during both the wind-down of the Vietnam conflict, which divided Americans, and the ongoing Watergate investigations, which only widened the credibility gap. George Lucas, who co-wrote and directed the movie, set the film in the last summer before everything exploded. The Cuban Missile Crisis was in September 1962, followed by the gradual build-up of the undeclared Vietnam “war,” the Civil Rights era, the sexual revolution, the free speech movements on college campuses and the drug era.

The adolescents in the film were the first of the baby boomers, born during the waning days of World War II. “The silent generation” was the term used to describe them when their younger baby- boomer siblings became the protest generation. Though Lucas resisted the term nostalgia, the world of 1962 had virtually vanished by 1973.

The movie charmed America and became one of the top-grossing movies of its era, garnering several awards and five Oscar nominations, including Best Picture, but lost to another Universal blockbuster, The Sting. Its success was ironic because Universal Studios almost dumped the movie into its made-for-TV division. Lew Wasserman, the head of Universal, had no faith in the film, referring to it as a “cheap TV movie.”

Graffiti is more important for the careers it fostered than for the film itself.

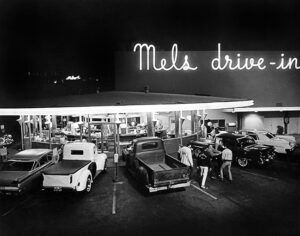

American Graffiti’s story was a simple one: a collection of high school students and recent graduates celebrate late summer by cruising their cars around their suburban town. Their shrines are Mel’s Drive-In and the AM radio show of the popular disc jockey Wolfman Jack, an actual DJ from the era. Take away the racy humor and we are back in Andy Hardy land, or the teenage films of Universal’s stars of the Depression and World War II, Deanna Durbin and Donald O’Connor. Wasserman should have appreciated Lucas’ film because he built his MCA producing empire on such television series about teenagers of the 1950s and ‘60s as Leave It to Beaver and Bachelor Father.

Ultimately, Graffiti is perhaps more important for the careers it fostered than for the film itself. Lucas began his ascent to superstar director and producer because of the film. He was being counted out as a wunderkind after the failure of his first feature film THX 1138 (1971), based on his 1967 USC film school short. Because his mentor, Francis Ford Coppola, red-hot after directing The Godfather (1972), agreed to produce Graffiti, Universal agreed to finance the low-budget film, which cost less than $800,000. It grossed over $55 million in 1973 and still provides revenues on DVD.

The film’s editor Verna Fields — the daughter of screenwriter Sam Hellman and the widow of editor Sam Fields — was a veteran picture and sound editor. She taught film at University of Southern California in the 1960s, where she connected many fledgling filmmakers to each other. At Universal, she introduced Lucas to Steven Spielberg, as well as to Marcia Griffin, and later hired Lucas and Griffin as editors on the documentary Journey to the Pacific (1968). Griffin married Lucas, becoming Marcia Lucas.

Marcia Lucas and Fields cut Graffiti and were nominated for the Academy Award for their work. Within four years, both would win the Oscar for best editing — Fields for Jaws (1975) and Marcia Lucas for Star Wars (1977). Fields was one of the few film editors who became a studio executive, when Universal appointed her vice president of feature production. But the title she really prized was “Mother Cutter,” given to her by the crew of Jaws because of her motherly care of them and her ability to swiftly edit any footage.

Walter Murch, A.C.E., CAS, MPSE — who later became both an Oscar- winning film editor and re-recording mixer — was not nominated for awards for his sound editing and mixing of Graffiti, the real accomplishment of the film. Murch’s innovative sound design and mixing incorporated rock ‘n’ roll songs of the 1954-62 period to accentuate emotional moments and create a quasi-documentary atmosphere. The songs really shaped the loosely formed narrative of a baby-boomer generation grasping for adulthood.

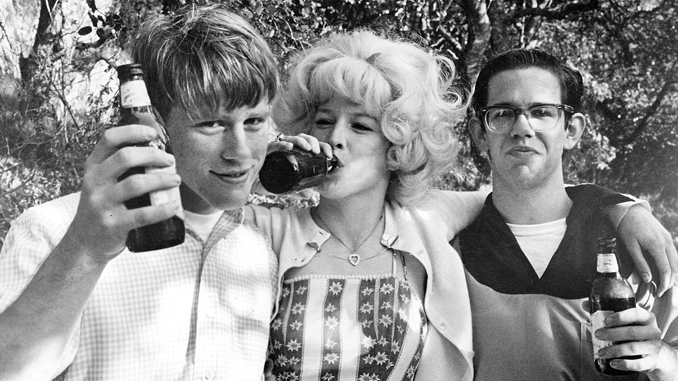

American Graffiti.Universal Pictures

Murch dimmed the songs for poignant impact, and emphasized their outsized sounds for the chicken racing and cruising scenes. For the scenes shot on location in the streets of Petaluma — the actual stand-in for Modesto — he positioned speakers so that the songs would be heard as source music when the cars sped by, merging into other songs down the road. “The music acts like a Greek chorus to comment on the events taking place,” Murch said in an uncredited interview quoted on www. americangraffiti.net. He had learned invaluable lessons about the power of rock music when he worked on the post- production sound of Gimme Shelter (1970).

On the acting front, television’s Ron Howard (The Andy Griffith Show) made the transition from child actor to adult star with American Graffiti, as well as a second hit TV series, Happy Days (1974-82), which was directly inspired by Graffiti. Cindy Williams went on to stardom with Laverne & Shirley (1976-83), a spin-off of Happy Days. Richard Dreyfuss had a series of classics after American Graffiti, including Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and his Oscar-winning role in The Goodbye Girl (1977). Paul Le Mat, who played the bad boy of the film, was better utilized by Jonathan Demme in two films, Handle with Care (1977) and Melvin and Howard (1980).

In a sense, the film is a seamless personal and artistic collaboration between friends Lucas, Murch and Coppola, who are considered to be the founders of the Northern California school of filmmaking. They had worked together previously and would continue to do so. American Graffiti is also a time capsule of the artifacts of the era. Because Coppola and Lucas were desperate to keep the cost down, they enlisted the help of car buffs who became extras in the film, driving their now-classic cars. The studio couldn’t afford to rent that many cars for film purposes, and that cooperation enabled Lucas to shoot the film in 28 days.

Whenever a movie in which a studio has little faith becomes a hit, studio executives call it a sleeper. Many of the hits of the late 1960s through the mid-1980s, films such as Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and Mean Streets (1973), fought their way onto screens through film festivals and proved studio logic wrong. Maybe it’s the executives who are the sleepers at the switch.