by Debra Kaufman

From hyper-real audio effects to vintage-sounding equipment, the sound in a Quentin Tarantino film is always distinctive. And from his Kill Bill: Vol. 1 in 2003 up to the current Inglourious Basterds, it has been the handiwork of supervising sound editor Wylie Stateman and sound designer Harry Cohen, MPSE, both of whom relish the experience of working with the director.

“Quentin is one of the most stylistically unique filmmakers of our generation,” says Stateman. “He is an auteur-type filmmaker––meaning he’s a writer, director, producer and truly a visionary type.” Part of Tarantino’s distinct style, says Stateman, is his relationship with his long-time editor, Sally Menke, A.C.E. “Sally has been a consistent part of Quentin’s method over the years, helping to explore his intentions as a storyteller,” he says. Cohen agrees, observing that he and Stateman are part of that process. “We figure out what works for Quentin and Sally and their process,” he adds.

That process is just a little bit different from the way many other films are done, according to Cohen. “We do as much of the work as we can upfront and try to get it to them so they can put it in the Avid and get comfortable with specific creative ideas,” he says. “This is an ideal way to start the dialogue between the filmmakers and sound.” As in any relationship with a director, it’s also about learning his or her personal preferences. Over the years, Stateman and Cohen certainly have learned Tarantino’s. “For instance, when Quentin wants something big, he isn’t necessarily talking about low end,” says Cohen. “He likes a wide dynamic range.”

From the first film they worked on with Tarantino, the process has been about discovery. “Quentin is essentially a member of the audience; he’s able to see things fresh,” says Stateman. “That’s a very unique quality for someone who brings to the table as many departments as he commands. But he’s a genuine audience member and has a great ability to see things as if for the first time. He can sense the way his audience would appreciate seeing things.”

“In discussing early on how Sally and Quentin wanted to represent the 1940s style, we offered a two-version approach… One way was to mechanically enhance the sounds to make it sound vintage. The second approach was a digital version using ProTools and plug-ins… The digital version won, but only after we explored the mechanical option.” – Wylie Stateman

When questioned how they would describe Tarantino’s style, Stateman and Cohen defer to Menke’s recent characterization. “Sally remarked a couple of months ago that his movies often live in the strange place where violence and humor intersect,” offers Cohen. Wylie agrees absolutely, adding “Quentin blends familiar themes with the avant garde and he insists on contrasting violence and humor—or making something so violent that it crosses the boundary of violence and becomes funny…if you get the joke. If you get it, you become one of his audience.”

Despite Tarantino’s very distinctive style, Stateman said there was no adjustment period at all when they first began working together in 2003. “Harry and I are very much in the mindset of adjusting to the filmmakers we work with,” he says. “That’s a big part of what Harry and I—and what Soundelux––bring to the table. We work for the filmmakers; we help them explore their goals and intentions. A big part of our job is to be as accessible and as easy to work with as possible.”

It would be easy to imagine Tarantino making demands in the audio suite. But Stateman shrugs it off. “Directors are demanding, especially ones that are complete filmmakers,” he says. “Great directors demand your absolute best. They demand deep thinking and high-quality execution. They demand that you listen to them and pay attention to the way they want to tell stories.”

Tarantino is a “wonderfully identifiable stylist” and, as such, “demands that we deliver within his style of really high-quality, highly intellectualized and well-crafted work,” according to Cohen, who explains that working with Tarantino also requires a deep knowledge of the history of filmmaking. “He’s a huge and very knowledgeable fan of films throughout the ages,” he adds. “A lot of times, his work contains purposeful references to other movies. He likes it when we’re aware of that.”

Just as Tarantino and Menke have worked together for years, so Stateman and Cohen have a 20-year history of collaborating, starting with Oliver Stone’s Talk Radio in 1988. “We’ve never regretted a moment of our collaboration,” Stateman says, noting that the two have “enjoyed working on a wide variety of filmmaking genres, including several with auteur, final cut directors,” such as Stone and Tarantino.

Cohen explains that the duo has “experimented with the shape of the process we do, and changed it to fit the style of different directors and their cutting rooms.” “It’s not just the director’s style but the collaboration between director, editor, production and post-production sound departments, taking the creative process from script to mix,” adds Stateman.

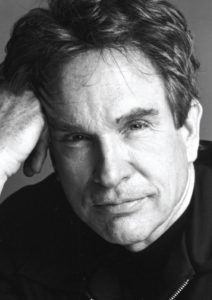

Wylie Stateman

Likewise, Stateman and Cohen have a nearly 20-year relationship working with editor Menke. “She is a very good communicator, and is very generous in terms of talking about her needs and Quentin’s intention; she’s really an ideal partner for us,” says Stateman. “The time that Harry and I have spent together has made us comfortable and familiar, and Sally is very much a part of a comfortable, very close-knit working environment.”

The familiarity that the three share enables them to use a kind of shorthand to communicate. “That familiarity defines the workload and focuses the effort on developing things that will be important to what’s on screen and in the final mix,” offers Stateman. “There’s not a lot of waste. And that’s what’s so wonderful about a small, close crew. We produce material quickly that goes into the track easily and effectively. It’s a very efficient working strategy.”

Cohen notes that this way of working means that they try “to bring what is essential and relevant to the mix. We try to pre-refine the material so that when we bring it in, what we’re presenting is the stuff that will help in play,” he adds. “If we’re missing something, it’s easier to add it on the mix stage––with all the sound elements present and the principals in the room––than it is to try to figure out which track, out of the many we’ve brought, needs to be turned off, to achieve clarity.”

One interesting part of the collaboration for Inglourious Basterds involved Nation’s Pride, a Nazi propaganda film within the movie. Stateman and Cohen went to Berlin to create the mix for it. “The movie-within-a-movie is in the 1940s style of Goebbels and Riefenstahl, and is the cornerstone of the third act,” explains Stateman, who reports that their first assistant, Brandon Spencer, and re-recording engineer, Michael Keller, CAS, accompanied them to Berlin, where they prepared the tracks and mixed for close to a month.

The challenge here was to make the movie appear as if it were mixed in the late 1930s or early 1940s. “In discussing early on how Sally and Quentin wanted to represent the 1940s style, we offered a two-version approach,” reveals Stateman. “One way was to mechanically enhance the sounds to make it sound vintage. The second approach was a digital version using ProTools and plug-ins.”

The mechanical version played back the mix on a 1930s Magnavox speaker with a metal horn. “It sounded interesting but more like an early 1930s sound than one from the early 1940s,” says Stateman. “The digital version won, but only after we explored the mechanical option.”

The digital version relied on a step-by-step chain to re-create the key aspects of the sound in that era. First the sound went into the Renaissance compressor to even out the dynamic range, and then the Reaktor tube emulator, which provided analogue-sounding saturation. The next step in the chain was into another Reaktor plug-in that was used to add wow, flutter and optical pops. Next, it went into the Meequalizer, which is modeled on an old equalizer and used to impart a vintage sound to the mid-range. From there, it went into Analog Channel, which simulates tape saturation; and lastly, into the Grm EQ, which was used to shape the overall sound, and roll off some low and high end. “Reaktor is a ‘framework’ plug-in that does many different things, depending on which ‘ensemble’ you open,” explains Cohen, who says there are well over 1,000 “ensembles” for Reaktor.

Stylistically, Inglourious Basterds’ sound may be a little sparser than Tarantino’s other films, says Cohen, but that’s in keeping with the movie’s period. “In these older movies, they didn’t cover every actor’s little move in Foley or layered sound effects,” he points out. “Back in those days, they might have had three or four channels––unlike today, where it’s limitless.”

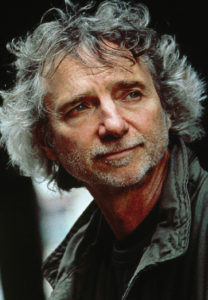

Harry Cohen

Yet there are moments when the sound track goes into incredible detail. “Sometimes in Tarantino’s films, you will hear things you wouldn’t ordinarily hear, in a kind of audio hyper-realism––such as the sound of the sugar when it pours off the spoon into a cup of coffee,” says Cohen. “There’s a scene in a restaurant and as the dialogue between two characters gets more intense, the sounds of the restaurant fade way, in an almost unnoticeable way and the sounds they make get more intense and detailed.”

There’s a reason behind those choices. “Quentin likes to narrow the focus of the sound track, often to enhance the intensity,” says Stateman. “In the end, audio is there to help support the telling of the story. It’s the invisible dimension.”

With regard to music, Tarantino’s long-time collaborator Mary Ramos was music supervisor on Inglourious Basterds. The director has a huge archive of vinyl records, says Cohen, and most of the music choices came from his collection. That’s all part of the process of working with the auteur director, who has a vision for every facet of the movie, not the least of which is the soundtrack.

“Working with a filmmaker like Quentin Tarantino is really about working with someone who knows exactly what he wants to accomplish and has the desire to involve himself in all aspects of the filmmaking process,” summarizes Stateman, who notes that Michael Minkler and Tony Lamberti were the new film’s re-recording engineers. “He understands, in detail, the story as a writer would. He understands, in detail, the goal and the intention of the film, as a producer would. And he is every bit the visionary director that people have come to know him as.”

by Debra Kaufman • portrait by Gregory Schwartz

Mixing motion picture sound was not Kevin O’Connell’s career goal from an early age. The Long Island native had another burning passion, which, thanks to a parental plea, was short-lived. But you could be forgiven for thinking that mixing was in his blood––given the more than 160 films he has worked on in that classification since the early 1980s.

He certainly got off to a great start. His first screen credit (as a sound technician, although he was a recordist) was the second of the original Star Wars sagas, The Empire Strikes Back (1980). Two years later, he was a full-fledged re-recording mixer, and soon amassed such film titles on his resume as Poltergeist (1982), Breathless (1983), Terms of Endearment (1984) and Dune (1984). More recent credits include Transformers (2007), all three Spider-Man movies (2002, 2004, 2007), The Da Vinci Code (2006), Memoirs of a Geisha (2005) and Pearl Harbor (2001).

Currently, O’Connell represents the Sound Branch on the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences’ Board of Governors. Ironically, he also holds the record for the most Academy Award nominations for Best Sound/Sound Mixing (20)––without a win. Additionally, O’Connell has been nominated 12 times for Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing by the Cinema Audio Society (CAS), and received an Emmy nomination for his work on Lonesome Dove (1989). He won the BAFTA Sound Award from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts for Spider-Man 2, sharing it with fellow mixers Greg P. Russell (his erstwhile longtime partner) and Jeffrey J. Haboush, along with sound editor Paul Ottosson.

Throughout his work in the field, O’Connell has partnered with other such notable mixers as Bill Varney, Steve Maslow, Gregg Landaker, Rick Kline, Donald O. Mitchell and Beau Borders, to name a few. In fact, Borders is his latest partner on the just-completed Michael Mann film, Public Enemies, which opens nationally July 1 through Universal Pictures. In the final throes of the Public Enemies mix, O’Connell found the time to talk to CineMontage about his work, his influences and how he came around to sound as a career choice.

CineMontage: How did you get into sound mixing? Did you have an early interest in sound?

Kevin O’Connell: No, not at all. Since I was five years old, I always wanted to be a fireman. So, in 1977, when I was 19, I took the test and managed to get into the LA County Fire Department as a brush firefighter, riding on the camp crew trucks and putting out brushfires. No one works harder than these guys.

During this time, my mother, Skippy O’Connell, was the assistant to the head of the sound department at Twentieth-Century Fox. I had been coming down to the studio since I was ten years old, but I never thought twice about sound. That summer, I was on a fire for three days in a row, and I came home covered with cuts and burns all over my body and 17 pounds lighter. My mother started crying and said, “I don’t want you to do this anymore. Please come down to the sound department and check it out.” So, reluctantly, I did.

CM: What did you do then?

KO’C: To be honest, it looked like the most boring job on the planet––sitting in a dark room all day watching reels of tape going back and forth. I was used to riding around in a fire truck with lights and sirens, running up and down mountains while being chased by brushfires. But I could see that she was so upset, so I said I would give it a try.

She got me a job over at the Samuel Goldwyn Studios and I started out as an apprentice. My official title was machine room operator. Every time the mixers got to the end of the reel, it was my job to rewind all of the tracks and reload them again. This happened several times a day.

“I didn’t know what to do because I was never formally trained. I was working with Bill Varney and Steve Maslow who had just won Oscars, and I have to admit, I did feel a little intimidated. Actually, I was horrified” – Kevin O’Connell

CM: Did you begin to like the work?

KO’C: At first, I hated it. I hated being inside; it wasn’t for me. But after a while, I started getting interested in it, looking out on the mixing stage and seeing how the mixers were affecting each sound. I had no idea how complicated creating a soundtrack was.

By the second week, I said, “Mom, this is the best job I have ever had. How can I ever thank you?” She said, jokingly, “You work hard and learn how to become a mixer and someday you go win yourself an Oscar––and you can go stand up on that stage and then thank me in front of the whole world.” I agreed, and my firefighting days were over.

CM: Speaking of which, you’ve been nominated for an Oscar 20 times, but haven’t won, right?

KO’C: I’m sure winning would be great, but I’ve had a great time just being nominated. Every time I get nominated, I get a ticket to one of the coolest parties in the world and every year I meet more and more exciting people. I have no complaints about not winning––although someday it might be nice to take that walk up to the stage. It sounds kind of cliché, but I really do feel honored just to be nominated in the first place.

Lunching at the LA Farmers Market in 1980, after completing The Empire Strikes Back, are, clockwise from front left, writer and executive producer George Lucas, re-recording mixers Bill Varney and Steve Maslow, recordist Kevin O’Connell, re-recording mixer Gregg Landaker, producer Gary Kurtz, sound designer and supervising sound editor Ben Burtt, and recordist Rick Canelli. Photo courtesy of Kevin O’Connell

CM: What was your path to learning to become a mixer?

KO’C: The machine loader works for the recordist, who runs the machine room for the mixing stage. I thought to myself, “That recordist job looks cool; I’d like to learn that,” so I did. Then, when a position became available, I moved up to the recordist position.

The next step up was to become an engineer or a mixer. I had become good friends with the mixers on the stage where I was working, and they always seemed to be having so much fun. So I decided to give mixing a shot. It turned out to be much harder than it looked; these guys were so good, they just made it look easy.

CM: What was your first mixing job?

KO’C: My first day as a mixer was on Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid (1982), starring Steve Martin and directed by Carl Reiner. I’m sitting on the main stage at Samuel Goldwyn Studios and I only have 18 tracks of sound effects in front of me but I didn’t know what to do because I was never formally trained. I was working with Bill Varney and Steve Maslow who had just won Oscars for The Empire Strikes Back and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), and I have to admit, I did feel a little intimidated. Actually, I was horrified.

I said to Bill, “What do I do?” He said, “Just put them all on minus-10 decibels,” and he winked at me. The movie starts out with a thunder and lightning storm with a car skidding and swerving down a muddy road––and all you heard coming out of the speaker was the loudest most distorted sound in the world! It was way too loud. Bill was yelling at me and I couldn’t hear what he was saying. When I looked over at Steve, he just looked shocked. So I leaned over to Bill and he yelled in my ear, “You’re playing everything too loud!” I asked what I should do. He looked at me the way only Bill Varney could look at you and yelled, “Lower it!” I turned it down to minus-20 decibels and it was still too loud. I had no idea what I was doing. The fact that I made it through that show was a miracle.

CM: How did things go from there?

KO’C: My next movie was Poltergeist with Steven Spielberg. I was as nervous as a guy could be. One day he leaned over and tapped me on the shoulder to give me some direction and from the second he said, “Hey, Kevin,” I didn’t remember a word he said because I was so nervous that he was talking to me!

I’ve been very fortunate my entire career to be surrounded by very talented co-workers, mixers and editors alike. If I have achieved any degree of success, I owe it to all of them for their patience, training and understanding.

CM: Who were your biggest influences in becoming a mixer? Did you have a mentor?

KO’C: I was very close to Bill Varney, Steve Maslow and Gregg Landaker when I was their recordist on The Empire Strikes Back, Ordinary People (1980) and Raiders of the Lost Ark. They were the best guys in town to work for. These guys took one of the toughest jobs in town and made it look fun. They were my mentors. Bill spent a lot of time talking to me about how to mix dialogue.

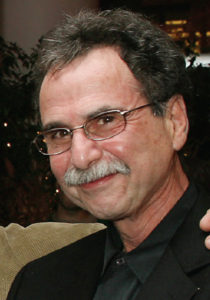

Kevin O’Connell, left, with director Michael Mann.

Photo by Bob Yamamoto

CM: How has the job of a re-recording mixer changed over the years? As sound has improved in the movie theatres, has mixing gained more respect?

KO’C: I believe that movies are getting more and more complex visually, and the more visually complex they get, the more they have to rely on the sound to sell those visual effects. Take a movie like Transformers, where you have a semi-tractor trailer driving down the road at 90 miles an hour and transforming into a robot. It takes very creative, talented people to make you believe that what you just saw could actually happen. The sound design team for Transformers was incredible. Director Michael Bay relied on them to make you believe his robots were real. It was the sound that brought these creatures to life. I do believe that directors are relying more on sound now than they ever did before.

CM: Do you have any advice for young people wanting to become mixers?

KO’C: People who want to become mixers should watch a lot of movies. They should also learn how to use ProTools. It’s a system that anyone wanting to learn how to mix or edit needs to master.

If you want to be a sound mixer or editor, you can download sound effects and music from the Internet, build your own library of sounds and––if you have ProTools––you can input any movie you want and practice cutting your sounds into sync with the movie. The more you know about ProTools editing and sound mixing, the easier it will be for you to get an apprenticeship in sound.

Nothing is more rewarding than watching a movie knowing that every sound at one time was at your fingertips.

by Michael Kunkes

The original Star Trek series, which ran on NBC from 1966 to 1969, boldly went where no series had gone before in terms of sound effects editing. The universe of the USS Enterprise was alive with sound, much of it musical in nature: computer banks, phasers, transporters, photon torpedoes, communicators, and alien and creature vocals. Much of that was due to the singular vision of writer/producer Gene Roddenberry, along with the inventiveness of Douglas H. Grindstaff, who served as the show’s supervising sound effects editor for the entire 80-episode run.

Grindstaff, who entered the industry in 1954 after service in the Korean War, won five Emmy Awards for his television sound work as well as the Motion Picture Sound Editors’ Lifetime Achievement Award in 1998. He also headed the sound departments at Paramount Studios, Lorimar Telepictures, Columbia Studios and Pacific Sound before his retirement in 1990.

“When I went to work on the series, Gene described to me what he wanted the Enterprise to sound like,” Grindstaff recalls. “I asked him if he didn’t think we were getting a little too ‘cartoony’ with the sound effects, and he told me, ‘Doug, I want you to think like an artist and paint everything with sound.’ That’s what he wanted, and that’s why the show sounded the way it did. He had a very strong vision; you had to give him what he wanted, but you also had to use your own instinct about what should be. You were either on his wavelength or you weren’t.”

Grindstaff and his crew built their tracks mainly from some material in the Paramount and Desilu sound effects libraries, as well as their own personal libraries. Additional sounds came from Paramount’s 1953 version of War of the Worlds. Sadly, the library he meticulously created, bundled and catalogued is now lost to history.

Douglas Grindstaff at the Moviola, working on Star Trek in 1967, from a news paper article. Photo courtesy of Douglas Grindstaff

Working with small TV budgets, Grindstaff maximized what he had. For example, to create the shimmering, musical sound of the Enterprise transporter, he blended together a few musical effects and electric generator sounds. Then, on a Moviola, he would create his own fades by shaving the mag sound with a razor blade at the desired point, a technique he learned from the late George Emich, who was Fred Astaire’s music editor at RKO, and who is co-credited with applying the click track to music editing. “I created my own fades because I didn’t trust the mixers to get it the way I wanted it,” Grindstaff laughed. “We also did all our own Foley and ADR looping.”

Other sounds were just as inventive. At Roddenberry’s insistence, each planet visited by the Enterprise had to have its own sound, and for these, Grindstaff would use variations of an orchestra tuning up. In one legendary episode, “The Trouble with Tribbles,” Grindstaff used screech-owls, doves and rat “vocals” for the voices of the furry pets, who came aboard the Enterprise and began reproducing at an alarming rate. “I had to go from a single Tribble to the sounds of thousands of them filling the ship,” he says. “I ran them backwards and forwards, put them on the variable speeder and edited loops, so I could have multiple tracks and mix them at different levels for different spots in the ship.”

The schedule was brutal. “You were making things every week, and that was the tough part,” he recalls. “I’d try and get as much ready as I could a couple of weeks before we got an episode, so that when the show was turned over to the editors, I had the sound effects pretty well set, and could tell them the right spots to put everything. I also always insisted on having a sound effects editor at every mix.”

Nearly ten years after the Enterprise concluded its five-year mission, Grindstaff was offered a job by Roddenberry on Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979). He turned it down. “Not long before that, I had gone to see Star Wars, and I flipped out,” he says. “I just said to myself, ‘Man, we blew it; we should have made a Star Trek movie a lot sooner.’ But I sure intend to go see this one.” Was he aware that he was creating something entirely new in sci-fi sound effects? “Hardly; I was too busy working for Gene.”

by Michael Kunkes • portraits by Gregory Schwartz

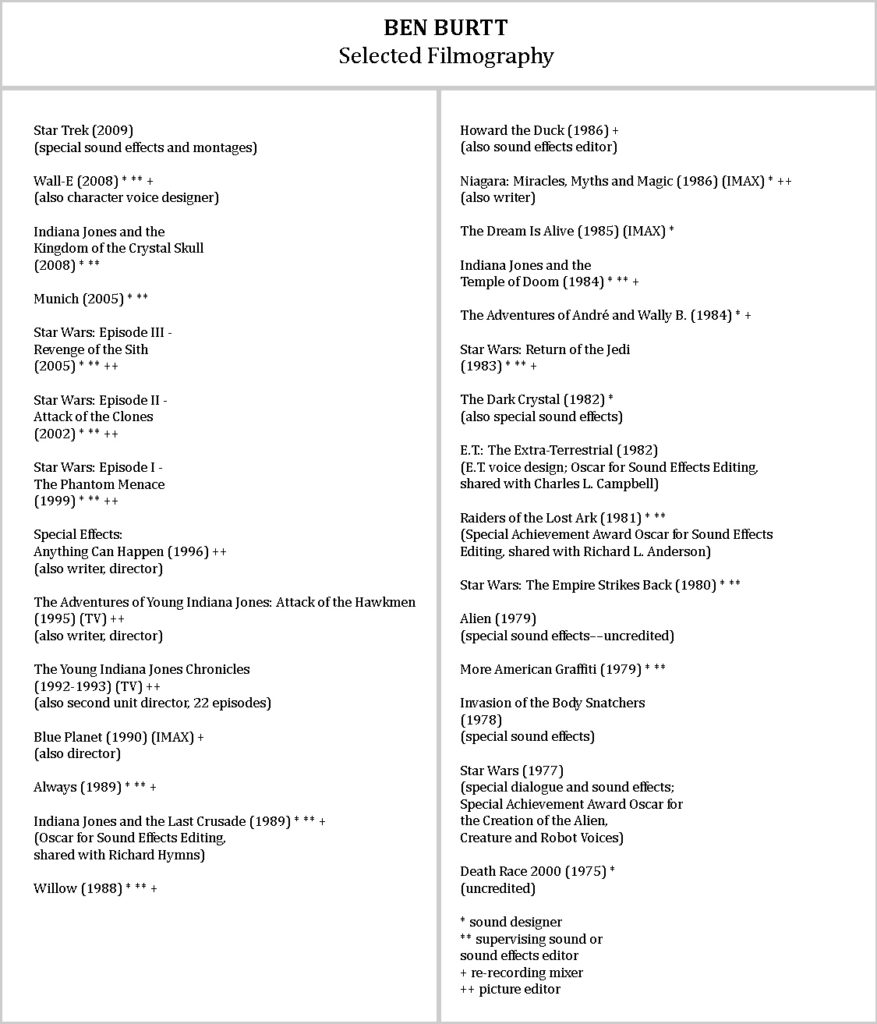

The crack of Indiana Jones’ whip, the roar of an Imperial TIE fighter, the hum and crackle of clashing lightsabers, the voice of Wall-E speaking through his circuitry… Almost anyone who has come of movie-going age in the past 30 years knows these sounds; they are part of worldwide pop culture. And all can be traced to the same source: sound designer extraordinaire Ben Burtt.

In 1976, Burtt was working alone in his makeshift sound lab in George Lucas’ San Anselmo, California house, a building known simply as “Parkway”—which served as the first headquarters of Lucasfilm. The year before, just after finishing his master’s degree in film production at the USC School of Cinema masters degree program, Burtt was hired to record sounds for a new Lucasfilm project with a working title of The Star Wars, replacing Walter Murch, A.C.E., MPSE, CAS, who was unavailable at the time. Surrounded by reel-to-reel multi-track tape recorders and an eclectic collection of mechanical and audio devices, he was turning his recordings of bear and other animal voicings into the tonalities of a Wookie called Chewbacca, speeding up Zulu recordings to create Jawa voices, blending the electric hum of an old TV set with the sound of a 35mm projector into the iconic sound of a lightsaber, and providing his own vocalizations to help create the voices of R2D2 and Darth Vader.

By the time the movie was finished in 1977, The Star Wars had become Star Wars, and the “new Walter Murch” had morphed into the first Ben Burtt, contributing his lifelong passion for collecting and building sounds to an emerging film language that would soon formally come to be known as sound design. It’s a language that Burtt once said has been evolving since The Adventures of Don Juan (Warner Bros., 1926), a silent film with a Vitaphone orchestra and the rudimentary sound effects of a sword fight.

More than three decades after Star Wars changed the face of fantasy and space opera forever, Burtt is again working in solitary fashion––this time on an undisclosed project in a much higher-tech facility at Disney/Pixar, but his methodology has not changed. “I’m sitting at my computer with sounds that are waiting to be made into something; I just don’t know what it is yet,” the four-time Oscar winner says with a laugh. His body of work in sound effects and sound design, largely accomplished at Skywalker Sound in Marin County, California, has enhanced over 40 motion pictures, TV series and documentaries. In his own quest to become a more complete filmmaker, Burtt has also by turns been a producer, director, writer, re-recording mixer and picture editor–– most notably on the second trilogy (or is it the first?) of the Star Wars franchise.

But it is his pioneering work in gathering organic sounds (natural, mechanical and sometimes musical), then customizing them into a performance that fits the meaning and action of a film, that has helped forge an iconic cinema aesthetic in much the same way the Golden Age of radio utilized sound effects to make an audience sit up, listen and listen hard.

Burtt spoke with CineMontage on the eve of the May 8 release of his latest project, Paramount Pictures’ Star Trek, directed by J.J. Abrams.

CineMontage: You are the first person, along with Walter Murch, to be credited with the title of sound designer. How did that come about in your case?

Ben Burtt: On Star Wars, I was recording and editing sounds, doing temp mixing and pre-mixes, and creating special dialogue––which was unusual at the time. There was discussion as to what title could apply to this odd, hybrid job that was crossing all the traditional barriers, combining the jobs of recordist, sound editor and mixer. On Star Wars, my credit became: “Creature and Robot Voices Created by Ben Burtt.”

The first time the title of sound designer was applied to me was when I did More American Graffiti [the same year Murch received that credit on Apocalypse Now]. It’s a title that is still unofficial and unrecognized by the Academy, but in Northern California we felt freer to create titles because there was less adherence to the existing traditions. I didn’t invent it; it was something that I believe George Lucas and Gary Kurtz came up with.

CM: How do you define the position?

BB: In some cases, a sound designer might invent a few specific sounds, turn them over to the editors and not necessarily be working with the director or imposing a signature on the entire movie. But at the other end of the scale, there are those like myself who are an influence all through pre-production, production and post. That kind of sound design is way more comprehensive because you are being asked to render a lot of creative contributions. That’s why it’s hard for the Academy to define sound designers, because the work varies so much from picture to picture. What we do is dictated by the unique needs of each production.

CM: How did Skywalker Sound evolve?

BB: When Star Wars was completed, the sound department at Sprocket Systems (the original name of Skywalker Sound) was two people: myself and Howie Hammerman, the engineer. The joke was that I would break the equipment and he would fix it. We began to grow as Lucasfilm got involved in multiple productions. In 1982, we moved into the ILM Kerner complex in San Rafael and opened our first mix room, Mix A, so that we could mix on our own. In 1987, we moved to the ranch near Nicasio. The original idea behind Skywalker Ranch was that George would have five films concurrently in some stage of production. When it became clear that wasn’t going to happen, Sprocket Systems opened itself to outside clients and eventually was renamed Skywalker Sound.

Ben’s Personal (Sound) Effects

1. Helium canister used for pitching up human voices into alien voices for Star Wars’ cantina scene.

2. Original Nagra stereo tape recorder used for field recording on Star Wars and all Indiana Jones movies.

3. Reel-to-reel recorder, Burtt’s main pre-digital tool in recording and sound editing.

4. R2D2 placard used to advertise Burtt’s use of Teac tape recorders.

5. Air conditioner cushion springs from roof at Pixar; used for sound of clanging swords.

6. Jumpsuit made to wear while recording sound effects for Return of the Jedi.

7. Mini-Moog synthesizer used for creating electronic tonalities of space in both Star Trek and Star Wars.

8. Custom-built arrows used to reproduce the sounds from Warner Bros.’ 1938 version of The Adventures of Robin Hood.

9. ARP 2600 synthesizer used to record R2D2’s voice.

10. Electric motor used to spin rods to

create wind sound.

11. Ice cube tray used for C3PO Foley arm movements.

CM: Who have been your mentors in sound design?

BB: First, there was Murray Spivak at RKO [co-winner of the 1969 Best Sound Oscar for Hello Dolly!], who created the sound effects for the original King Kong in 1933. His work in King Kong was the beginning of sound design for fantasy motion pictures. The voice of Kong, the sounds of the jungle, the creatures, and the screams—all were individually created and nothing like it existed before. He was able to mix two, perhaps three tracks together at a time, using two optical playback machines, making a loop and blending things together. When people make monster movies today, they still don’t gravitate far from those principles and techniques.

Then there is Treg Brown, credited as the editor of the Warner Bros. cartoons from 1933 to 1966. He also created all the sound effects. He was a huge influence on me, because he used real sound effects for comic purposes and for exaggeration. The Road Runner is made from the sounds of high-speed aircraft. If Wile E. Coyote crashed into something, the impact wasn’t the sound of a cymbal crash or a bass drum hit; it was Treg Brown cutting in a thunderclap and a destroyer alert siren. Associating these real-world sounds with the events in the cartoon made the action seem all the more realistic and melodramatic. I found this same approach gave dramatic credibility to the fantasy film. For me, Star Wars was one gigantic Warner Bros. cartoon.

A third major influence was Jimmy MacDonald at Disney, who I once had the chance to meet when I was just out of school. He was a master at building props that were used to actually “perform” sounds for specific characters, such as a talking bee or a singing frog––or the sound of Mickey Mouse’s car with all its voice-like rhythms and percussions. [MacDonald was also the voice of Mickey Mouse and, like Burtt, was a drummer.] What was so effective about his work over 40 years at Disney was that he was a performer and, like a musician, performed the sounds that he built. The end result was something that came out of his soul as a musician. My best sounds have usually been the result of some sort of interactive performance with a prop or technology.

CM: How have these people influenced your own approach?

BB: It’s all part of what I call the “language” of sound effects. As a sound designer, it’s to your benefit to understand what came before you, because audiences are somewhat conditioned by those traditions. That way, when you go to create a new monster or spaceship sound, you don’t have to imitate what came before, but you can come up with something brand new that builds on the past. For me, one of the things that is most exciting about sound design right now is the interface between our brains and our sound effects libraries. For example, I discovered on Wall-E that I could do things like using a light pen and tablet to trigger sounds and alter their pitch by “performing” with my hands. That’s something MacDonald might have done––build a device that allows you to perform a sound. That is so important, because it allows you to inject a performance, to use your own sense of musical timing and control the texture of a sound. That’s an advantage we have today that Spivak or Brown never had.

CM: What makes a successful sound designer?

BB: It boils down to the ability to select or create the right sound for the right moment, to pick the thing that dramatically tells what needs to be said in that moment. That applies to dialogue, music or sound effects. I don’t think successful sound design has ever been about the quantity of sound or how many tracks you can use at once. We all know that there are real limits to that. We suffer nowadays from too many films being filled with noise––partly because the technology has made it so easy to pile things on. I have to constantly re-learn the lesson of subtractive rather than additive sound orchestration.

CM: How can sound design provide more bang for the buck in smaller movies?

BB: You can do so much to color in the drama of a movie with sound without hiring a giant crew. The technology now is efficient enough that you can do a great deal of work on your laptop. When I was cutting Star Wars: Episode III, I was sitting at an Avid where I was editing picture. I could turn my chair to the left, where there was a laptop connected to my library with a mini-keyboard so I could do quick sound design. I also had a mic with which I could record my voice for something temporary and export that into the Avid to try against picture. Then I could turn to my right, where I had another computer that had CG models of the main characters, vehicles and environments. I could do simple, limited animations of a ship going toward a star field or put an image of a CG character into an environment. I could choose a camera angle, lens focal length and movements.

These animatics became the guide from which to develop new shots as we went along. The upshot of this is that there are desktop tools available for one editor to tackle a wide range of sound and picture editing tasks. Whether you are doing “tentpole” or “pup tent” movies, the editor today has some very economical and powerful tools at his command.

CM: How did you come to work on the new Star Trek?

BB: In October 2008, I was invited by J.J. Abrams to come to a screening, and perhaps offer some advice. They were searching for sound effects with a distinctive signature that also indicated the best way to orchestrate the density of sound effects, music and dialogue that the film demanded. I started to feed them some ideas, and that led to, “Can you make things for us?” So, in a series of steps, I came on board and ended up creating a library of almost 400 sound effects, as well as designing and pre-mixing certain key seq-uences from bottom to top. My credit on the movie became “Special Sound Effects and Mon-tages,” which was the best way I could sort of fit myself in.

Ben Burtt in the Mojave Desert in 1976, recording the original “guy wire twang” that became the sound of Star Wars’ laser blasts. Photo courtesy of Ben Burtt

CM: What is your personal re-lationship with the whole Star Trek zeitgeist?

BB: You might say I’m a longtime “latent trekkie.” When the show came out in 1966, I was a freshman at Allegheny College––and we had no TV reception, believe it or not. I would have my father record the shows on reel-to-reel audio tapes and send them to me. I listened to the first eight episodes before I ever saw the show. That’s how I came to love the sound effects on that first series; they were so well done that they fired up my imagination and brought the show to life.

CM: How did your work on the new Star Trek movie pay homage to the original series?

BB: The supervising sound editor on the original series was Douglas Grindstaff [see sidebar, page 30] and, with the urging of Gene Roddenberry, he and his team really raised the bar and did some things that no one had ever done before in science fiction. They articulated sounds for the entire ship––every room sounded different, and every piece of equipment had a unique sound to it. Secondly, they used real motors and radio sounds, to give it a sense of reality, but also a lot of musical sounds and tones. If someone pressed a button on a console, it made a little musical melody. There was sensitivity to making things that had an emotional feel to them, and the detail they went into was unprecedented. I carried those methods into my work on the first Star Wars movie, and that guided a lot of my thinking when I began creating sounds for Star Trek.

CM: Why did it take nearly 30 years for you to work on a Star Trek movie?

BB: I was on staff at Lucasfilm during a lot of that era and was completely wrapped up in Star Wars, so the space in my life for space was already completely filled!

GM: What challenges did working on the new film present?

BB: It was very unusual for me to be on a movie that was not in flux visually. I am used to starting even before shooting begins so that I can build up a library and be on hand during picture editing. This way I can inject ideas and do R&D as I go along to make decisions about what will and won’t work. On Star Trek, this process had to be cosmically compressed. However, it was very exciting because the picture was complete and everyone could focus creative attention on sound. We didn’t have to contend with the usual disruptions of picture changes and incomplete visual effects. Otherwise, I don’t think I could have created and pre-mixed 400 sounds in just six weeks.

Ben Burtt before a mural image from WALL-E at Pixar’s studios.

CM: What was your mission during the time you were on the movie?

BB: I was interested in making two things happen. One was to make the film sound like a classic science-fiction movie–– which means addressing a legacy that goes back to the beginning of the genre. Secondly, to attach it specifically to what I loved about the original TV series. I was interested in making sounds using some of the same techniques that may have been used in the ‘60s. It meant going back to things like test oscillators, spring reverb chambers, feedback and mechanical sounds. I wanted to recapture the sense of sound effects done with a musical sensitivity. I wanted to not only pay homage, but to expand and translate those original concepts into something grander and more powerful.

CM: What was your interaction with director J.J. Abrams?

BB: I would have sessions with him on a daily basis. I would audition sounds in context with dialogue and music. Once he was satisfied with the direction of a sequence, I would pre-mix it, and pass along additional sounds to supervising sound editor Mark P. Stoeckinger. We would all review it in the mix with re-recording mixers Paul Massey, Andy Nelson and Anna Behlmer. J.J. would make the final decisions on balance.

CM: What did you bring from your experience in Wall-E to Star Trek?

BB: Like Wall-E, Star Trek is a movie jammed with sound, and it brings to the forefront the whole challenge of orchestration, of picking the right set of sounds for any given moment. Also like Wall-E, Star Trek is a very fast-paced movie. You can design sounds that might be interesting, but shots go by so quickly—40 frames here, 28 frames there––that by the time you hear something, the shot’s already gone. The sonic density of Wall-E forced me every day to weed out and orchestrate sounds so that they went well together.

When I came to work on Star Trek, which is a hyperactive movie in its own right, I was able to turn to J.J. and say, “I know there’s two dozen things happening in this shot, but we have to decide what we want to hear; maybe only two well-placed sounds will deliver the goods for that shot.” A lot of the discussions in the final mix were about that. You don’t just want a wall of noise. What you want to hear are the specific notes and melodies of sound effects, dialogue and music, each having its own turn as the main “theme.” You have to carefully weed through and pick the right things, and Wall-E helped me get better at that.

A scene from the new Star Trek movie. Photo by Industrial Light & Magic.

Copyright 2008 by Paramount Pictures. All Rights Reserved.

CM: What do you think is the future of sound design?

BB: I don’t think that audio creation technology has kept up the pace with what we do visually. There’s a whole new set of tools waiting to be built that will allow us to create, alter and mix sound effects and voices with results that have never been heard before. If they can make Brad Pitt appear to be 17 as in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, then there must be potential means of synthesizing and manipulating audio to create exciting new worlds of sound. I’d love to be able to do more of that.

CM: What are the best creative moments for you?

BB: For me, it’s the simple things. When I was doing Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, I was looking for sounds for the skulls, some magnetic effects and unseen telekinetic forces. Then one night, I was walking out to my car, when my attention was drawn to the buzzing sound of a mercury vapor lamp in the Skywalker parking lot. I recorded it, slowed it down, played it backwards, and put it all over my keyboard. I got so much mileage from that one little buzzing sound which seemed to fit the bill.

On Star Trek, creating a two-second gap of silence, then adding a backwards feedback “shimmer” gave dynamics and accent to a supernova explosion. On Wall-E, a quiet moment with nothing heard but Wall-E’s fire extinguisher propulsion in space was audio poetry to me. Once again, it was all about finding the right component, keeping it simple, and finding something emotional.

CM: What part of the process do you like best?

BB: The thing I love most is the moment I put sound or music in for the first time against a picture that previously had nothing playing with it. I get the same charge doing this as I did when I was a kid putting sound against my silent home movies. That moment is like giving birth to something, and it is part of the thrill of participating in the magic of the movies.

Editor’s Note: More of this interview with Ben Burtt, including outtakes from this article, can be found on www.editorsguild.com.

by Michael Grotticelli

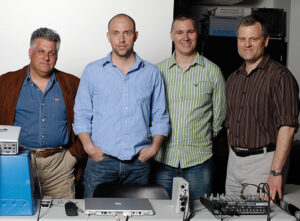

There’s an old adage in show business that if you want to ensure success, avoid working with kids and animals. Don’t tell that to picture editor Craig Cobb and supervising sound editor Louis Bertini, MPSE, who help post one of Nickelodeon’s hit shows, The Naked Brothers Band.

Cobb and Bertini also worked together on all six seasons of HBO’s Sex and the City and said they find The Naked Brothers Band equally challenging, but in different ways. “The truth is that a number of us who’ve worked on both Sex and this show will tell you that there’s not a big difference,” Bertini says. “The approach and constriction of the audio elements that we bring to Naked Brothers is rather similar because of the New York ambiance–– except that the sound effects for this show have a larger cartoon element. However, both shows are not sitcoms, so there’s no laugh track.”

“Getting them to listen to what I have to say is the hardest part,” Draper explains. “But then again, that’s no different than at home.”

The Naked Brothers Band started in 2005 as an independent feature-length “mockumentary” that was released in theatres (it won Best Family Feature at the Hamptons Film Festival that year). A flurry of Internet buzz followed. As a regular TV series, it has evolved from a low-budget independent production to one of the top series on the kids network. Produced by Kidzhouse Entertainment, the show follows a group of kids in a popular teen band––at home and on the road. Other characters include a kid manager, a nanny and a large adult bodyguard.

The show is a family affair, including two real-life brothers (Alex and Nat Wolf) and their father (Michael, who is the co- executive producer and music supervisor of the show), while their mother (former thirtysomething actress Polly Draper), who created the show, works behind the scenes as executive producer/head writer/director.

Draper is directing five of the 13 episodes of the current season, often relying on a backstage monitor instead of walking onto the set to keep track of block- ing. The real-life mother/sons relationship sometimes penetrates the set as, during one long production day in July after Draper gave one of her sons a stage direction, an exasperated voice could be heard saying, “I know, Mom!”

“Getting them to listen to what I have to say is the hardest part,” Draper explains. “But then again, that’s no different than at home.”

As the lead singer and songwriter for the Naked Brothers Band, Nat is acknowledged as a child prodigy. His father is an accomplished jazz musician himself who served as the band-leader and musical director of The Arsenio Hall Show from 1989 to 1994. The show is shot on a soundstage in Brooklyn and posted at Soundtrack in Manhattan.

Each episode is shot with two Sony HDCAM F950R cameras in about five days. Camera operators now shoot the show in 16:9 high definition (HD) while framing for 4:3 audiences. They often use some CGI and green screen effects for the show and its music videos. On-set digital imaging technician Rick Nagle shades both cameras on the fly from a backstage rolling cart. The setup is highly portable, allowing him to move from the indoor set to an outdoor location when required.

Cobb said that because the show is very improvisational in nature––causing him to have to deal with so much footage––he approaches the show with the eye of a documentarian.

Intensely watching a CRT monitor during production, Nagle said that he tries to match skin tones and stay consistent to the overall look of the show. Now in his third season on The Naked Brothers Band, he knows what the producers want and how the final playback should look.

Once the footage has been captured for a specific episode, Cobb puts together a rough assembly in four days on Apple’s Final Cut Pro HD software (unique for a primetime series). Then Bertini takes over and spends an additional four days adding sound effects and replacing any unwanted dialogue. Simultaneously, the show’s music editor,JohnDavis, is working on the band’s musical numbers. Once the final sound mix is complete, Cobb does a final check of the lip sync between the picture and audio track, paying close attention to the music performances. This often requires some adjustment using FCP’s scrubbing tool. In total, each episode takes about four weeks to complete.

“Sometimes I throw in a one-frame jump cut to make the scene look right, depending upon the individual performance,” Cobb offers. And therein lies one of picture and sound editorial’s biggest challenges: Working with non-professional actors often means having to cull through numerous takes before finding the right one.

“I have to watch all of the dailies to find the gem among the performances,” Cobb explains. “Since I have been doing the show for so long, I know what the producers are looking for and have become good at finding it rather quickly. When I see these moments, I start my cut of the scene with them and work backwards. It does take a lot of time and creativity to make things look good.”

The show’s work flow has also evolved over the three years it has aired. The first season show’s footage was down-converted to standard definition (SD) during the encoding process in order to prepare for edit sessions. This past season, the footage was down-converted to Digital Betacam on the set in a small video village setup. Cobb’s assistant editor, Jason Barnes, then digitized the dailies into the QuickTime file using the ProRes 422 codec. “We’ll often use a day just to polish what’s been set up in the offline edit,” Cobb says. “So time is very critical. And we do it all in Final Cut Pro.”

This season, the show is broadcast in standard definition 4:3, so the tapes will be coming back and loaded into Cobb’s work- station using Apple’s ProRes 422 codec within a QuickTime file to maintain the highest quality possible. All video effects and online editing is also completed in Final Cut Pro.

“The 16:9 SD workflow was the plan for the 2008 season, but that has changed,” Cobb reveals. “We’re working in 4:3 SD with the ProRes 422 codec, so we’re cutting in a broadcast-quality format that we’ll later output without having to recapture all the footage.” Because he needs to look at everything captured on the set, Cobb uses a lot of drive space. Last season he averaged 300GB to 400GB per episode. The final masters will be delivered to Nickelodeon in SD 4:3.

If they decided to produce an HD version in 16:9, there will be lots of issues to be concerned with regarding the wider aspect ratio, the edges of frames and what the director and producers want––or don’t want––the audience to see. Also, in repurposing older footage, all of the old footage will have to be re-digitized in 16:9.

“There are many issues to consider,” Cobb says. “If I were able to cut it 16:9, I would be able to keep an eye on the out- side edges of the frame. Since I only cut it in 4:3, I don’t get to see what’s going on in the entire frame. Therefore, should an HD version be required, potentially a lot of adjustments will have to be made in the final edit.

“Occasionally, we’ve had to look at the 16:9 footage to reposition a couple of shots and I’ve seen light stands and such that will have to be removed somehow in a 16:9 version of the show,” Cobb adds. “However, everything has been shot in 16:9 HD, so we will never have to stretch any images to fill the 16:9 frame.”

For his part, Bertini said that the audio becomes a character in the show. “The sound editing is subservient to the video given to us by the director, but I always try to bring the outdoor sounds of the city into the studio set,” he said. “We add lots of sound in order to accomplish that–– whether from a sound effect library or elements we capture ourselves.” He also reveals that a lot of the same sound elements used in Sex and the City are used for The Naked Brothers Band, although he changes the pitch, the speed and manipulates them in different ways to make them sound different.

The Naked editorial team: Stu Deutsch, left, Jason Barnes, Craig Cobb and Louis Bertini. Photo by John Clifford

Working from Cobb’s first-cut video track and sound elements recorded by the show’s recording supervisor, Stu Deutsch, Bertini mixes the dialogue, adjusts flubbed lines when necessary, eliminates unwanted fan noise from the cameras, adds sound effects to emphasize a certain point in the script, and generally smoothes out rough audio spots in the scenes. This often takes four days of finessing. Re- recording mixer Colin Weeks then mixes the final elements together on a Digidesign Icon audio mixing console at the Soundtrack facility before the episode is delivered to Nickelodeon for broadcast.

Bertini works with Digidesign ProTools, generating .WAV files for Cobb to complete the episodes. He said the .WAV for- mat is useful because it contains the most metadata and makes the post process run more smoothly. He uses about 20GB of storage to hold the dialogue for each episode. That’s in addition to about half a gigabyte for ADR and 10GB for original and stock library sound effects. Bertini estimates he can use four 250GB drives for an entire season. And that’s just for the audio.

“What always amazes me on this show is how quickly inspiration can come with these kids…and how quickly it can leave,” Cobb says. Bertini agrees with him that working with kids makes things “interesting” during the post sessions. “Because the actors are kids, there’s a tremendous amount of ADR work that has to be done––much more for this than was ever done for Sex and the City,” he explains. “The kids make mistakes; they mumble. For me, it’s a lot of extra work, and I have learned to work fast. After two seasons, I know the routine.”

Cobb said that because the show is very improvisational in nature––causing him to have to deal with so much footage––he approaches the show with the eye of a documentarian. “The biggest challenge is staying true to the script while also trying to capture the magic on set, which often is not written down,” he says. “Then, you have this added layer of music that you have to bring into it. Remember, the kids are not actors. It’s a real challenge. You have to use a use a lot of different thought processes to make this show work.

“Unlike with shows that use experienced actors, I can’t depend on them to do exactly what they are supposed to do,” he said. “That’s when the magic happens and it’s what makes this show really shine. Sometimes it’s often messy to get to that point, but in the end it’s well worth it.”

What’s clear is that through a lot of hard work and “serious, but not too serious” effort, the show stands out among the heavily structured shows that now dominate children’s television. According to Draper, she works hard to give the show “a very improvised, uncalculated, spontaneous feel.” She’s also making a show for adults as much as for kids, so that families can share time together at home watching.

“I always hope that parents will enjoy the show as much as the children,” Draper says. “I’m also very inspired by my son’s songs, so a lot of the feelings and thoughts in the episodes revolve around those. We treat this show like an adult comedy, not like a typical kids show. If a joke goes by unnoticed, that’s all right with us. With the third or fourth viewing, kids will pick it up, as opposed to most children’s fare, where most jokes are signaled and cued.”

by Vince R. Gutierrez

A very summer, my family got invited to the Paramount Studio picnic by my uncle, Al Zuniga. New movie and TV stars would appear; most notably for me were the Cartwrights from Bonanza. Al was Paramount’s trailer editor and his job really intrigued me. I decided that film editing was my goal, so I would spend days in Al’s cutting room learning about everything from 35mm film stock to synching sound––and the infamous way to find the emulsion side of film by using the “lip test.”

In 1964, the union roster was low enough for me to get hired at Paramount, starting in film shipping. Al’s mentoring had paid off and I was on my way. It was awesome to walk around the lot and actually see John Wayne, Kirk Douglas, Dean Martin, Jerry Lewis, Steve McQueen, Ann- Margaret and Elvis Presley in the flesh.

After my Vietnam-era stint in the Army, I returned to Paramount and joined the NBC editorial staff as an apprentice, working exclusively on Bonanza and The High Chaparral. The next season, I had a chance to move into sound editing, specifically ADR––called “looping” in those days. Since it was a $50 bump in pay and I was a newlywed, the choice was pretty easy. Using 35mm sound loops, I spliced each line individually with leader in between. The actor would hear the line, then repeat it until we got a close match. Thousands of feet of film were recorded and, of course, all had to be edited.

Before digital editing, the final sound- track for television or features was accomplished using dozens of sound-edited reels of effects, dialogue and music––all synchronized to the 1,000-foot picture reels; six picture reels for an hour show, ten or more for a feature. A reel could hold from 15 to 30 units, all loaded onto reproducers in the dubbing channel and linked to the mixing board on the stage. Mastering was on three-channel 35mm full-coat mag masters, and voice was slated each time a new take was done. Needless to say, mixers had to be on their game and cue sheets were key. Since the mixing process was obviously tedious, ping-pong tables became the vogue on stages around town. You could actually get in two or three games while units were rewound or reloaded.

In the 1970s, an innovative post-production audio editing process, the PAP system, was developed by Joe Kelly, Rick Larson and Bill Wistrom at Glen Glenn Sound. It utilized video tape picture locked to film by time code and built dialogue and effects onto a two-inch, 24-track reel of tape. Sound editing was done by using quarter-inch dailies and tapes transferred from 35mm sound libraries instead of the normal film mag stripe sources. This innovation limited the number of film units needed, thereby pioneering the multi-track post audio era. Gone were the days of lugging hundreds of reels of film from stage to stage and doing thousands of butt splices.

In 1974, I became sound supervisor for Michael Landon on Little House on the Prairie, and our association lasted for over 17 years, spanning three successful series. Michael also became my second mentor by generously giving me a chance to write for Little House, Father Murphy and Highway to Heaven. It was incredibly gratifying to start with the written word and then follow the process until the final mix. Here I was creating shows alongside the same Little Joe Cartwright whom I had met at a studio picnic so many years before!

In 1991, I became general manager for Rick Larson and the Larson Sound Center, where I combined sound supervision with studio management. Television was our main clientele, with TV movies, drama series and sitcoms being the foundation of our success. Scott Millan and David Fluhr were part of our early team and both have gone on to be awarded Oscars and Emmys alike.

Historically, there was always a clear distinction made between feature sound editorial and TV sound editorial. Features had larger budgets, expansive post-production schedules and huge crews. Television was staffed leaner and had smaller budgets, yet was still expected to turn shows around every five or six days. Because of this, I believe TV helped innovate faster technology.

WaveFrame, Fairlight, and now ProTools have emerged from the TV editing rooms to be in every studio in town. Who would have thought we could edit an entire show, upload it to an FTP address and then download everything and mix without ever touching a single piece of film? New tools and plug-ins are created every day as our industry continues to grow, but it still boils down to our craft.

I’ve been honored with two Emmy Awards and currently serve as Sound Editing Governor with the TV Academy. Believe me, I understand what all of us do together to create the magic that is entertainment. So, let’s all enjoy it and pass the popcorn.

by Robin Rowe

Like the Undead that it depicts, the vampire movie never really expires––or even goes away. It just keeps resurrecting itself in new stories for another generation. This season’s blood-sucking entry, geared to teens and young adults, is Twilight, based on Stephenie Meyer’s 2005 best-selling novel of the same name about a 17-year-old girl who falls in love with a…you-know-what. Meyer has already written three sequels, so this may be the start of a new franchise. Summit Entertainment releases the feature November 21.

“Summit gave me five scripts they wanted to make,” says Twilight director Catherine Hardwicke. “Twilight was the one. But after reading Stephenie Meyer’s book, we ended up throwing out the existing script and sticking much closer to the book.” Hardwicke chose her frequent collaborator Nancy Richardson, A.C.E., as editor. “I met Nancy over 15 years ago. We were both working on a Tim Robbins and John Cusack movie called Tapeheads.”

Supervising Sound Editor Frank Gaeta.

“That was even before I was an editor,” adds Richardson. “I worked on Tapeheads as a video coordinator, which means that I created anything that appears on a video screen in the film.” Richardson also edited Thirteen and Lords of Dogtown for the director. “I like working with Nancy because she has a strong sense of story, character and performance,” says Hardwicke. “She’s fearless in stating her opinions. Sometimes we disagree, but hopefully it makes each of us work harder to support our ideas. Nancy has another great quality I admire in an editor: She’s fast! She whips a scene into shape very quickly––but very close to a final form.”

Editing quickly would prove indispensable on Twilight. “They added a week of principal photography, and two days before starting that photography we learned––by reading in the trades––that our release date had been pushed up,” relates Richardson. “We were supposed to release on December 12, but the Harry Potter movie pushed back from November 21 to June or July of next year. Our studio looked at that slot and said, ‘Oh, we should pop in there, because it’s basically unopposed.’”

For presentation’s sake, Richardson says she always has music in anything she cuts. “Catherine will shoot a hair and makeup test, and I’ll cut it and put music to it,” she explains. “We did that in Lords of Dogtown, with Heath Ledger and Emile Hirsch. Catherine showed that to the studio, and they were delighted with it.”

“Catherine is extremely visual,” says Richardson. “Everything is storyboarded, or she gets photographs to visualize every single scene. When you get the dailies, it’s pretty clear the direction you need to go. It’s not really an animatic, but she’ll shoot a rehearsal. We’ll pull that into the Avid, and I’ll cut it and send it back to the set. In some cases, I’m selecting a little look or point of an actor that was funny or cute and that was improvised during a rehearsal. That then becomes storyboarded as part of the shoot.”

“Shortening is always a huge challenge,” she continues. “I think my first cut on Twilight was two hours and 22 minutes. Catherine likes to be ruthless right away. Our goal was to get it under two hours: ‘Pick up the pace, pick up the pace, pick up the pace.’ I do pace pass after pace pass. Do we need this pause? Do we need these two lines? Catherine calls it my ‘stealth trimming’ because she can’t tell. Suddenly, it’s 20 seconds shorter in a scene. We made some pretty radical cuts right in the beginning.”

The principal photography was shot in Portland, Oregon from February to April 2008. “We had weather issues that were so difficult,” Richardson reveals. “In a given day, it would rain, snow and the sun would come out. There were matching problems. There were days where it got completely rained out. When we’re on location, they’re shooting five days a week, and on Sundays, Catherine would come in and give me notes on the cut scenes. I don’t think much about reels until a lot of the film is shot.”

“I don’t have a traditional facility; I work out of my home––most of my editors do, too.” – Frank Gaeta

Richardson got a development deal as a screenwriter fresh out of UCLA film school. “I had friends from UCLA who’d gotten financing for a picture,” says Richardson. “They knew me as a screenwriter, not as an editor, but they decided to take a chance. That film became Stand and Deliver. After that, I was an editor.” The two films of which Richardson is most proud are Ramón Menéndez’s Stand and Deliver and Charles Burnett’s To Sleep with Anger. She also edited Maya Angelou’s Down in the Delta, along with Step Up, Selena and Why Do Fools Fall in Love. Richardson also serves on the Guild’s Board of Directors and teaches at UCLA. Her Advanced Film Editing and Pathways in Post-Production classes started in October.

Twilight was posted at Tribeca West in Santa Monica. “Frank Gaeta is our sound supervisor; he was also our sound supervisor on Thirteen,” says Richardson. “We throw reels to him and he sends us temp sound effects or little mixes back over that we cut into the reels. Music editor Adam Smalley has been a hugely significant collaborator on the film; he is the liaison to the composer.”

Conveying Emotions Through Music

“Twilight is a phenomenon,” says Smalley. “The author has excellent taste in music; the whole music landscape is great. She dedicated the book to the band Muse. On her website, there’s a playlist of what she was listening to when she wrote the story. We have amazing bands, like Muse, Radiohead and Linkin Park. Perry Ferrell from Jane’s Addiction wrote something as well. Rob Pattinson, who plays the lead vampire, also happens to be an incredible musician.”

Even though Twilight is a vampire story, it’s really a love story between a mortal and a vampire, according to Smalley. “Catherine Hardwicke says most of her subject matter has to do with teen angst. The emotions are peaked so high. That’s what the music has to convey.” And Smalley worked on that conveyance by experimenting with the three versions of the stars’ first kiss that Richardson cut.

“This is really an evolving industry… The lines between editorial and mixing are getting blurred. You see that happening all over town.” – Frank Gaeta

Twilight proved a change of pace from Smalley’s previous film. “I did Kung Fu Panda with composers John Powell and Hans Zimmer,” he says. “The soundtrack for Twilight is a little more sophisticated and edgier than an animated feature. Carter Burwell is the composer.”

Since the music editor is often hired before the composer, he or she must deal with a temp score. “I can put up 50 pieces of music against one scene to see how it changes the feeling of the scene,” explains Smalley. “I have to create a film score, from beginning to end, of temporary sound. The composer has six to eight––maybe ten–– weeks to write an hour and a half of music. These temps have become an essential part of the process. If a director or editor or producer wants to explain to a composer what a scene needs, it’s easier to put a piece of music up against it, rather than try to talk about music.”

Smalley is completely ProTools-based. “We go from what Carter writes in Digital Performer,” he says. “I have terabytes of library music. I’ll start cutting a version that he’ll use as a jumping-off point. He’ll post a demo.” Carter lives in New York and Smalley doesn’t get together with him until the end of this process, when the recording starts. “I’ll bring my editing gear there; it’s a basic Mac-based editing rig,” Smalley adds.

A scene from Twilight. Courtesy of Summit Entertainment

Image-Driven Sound

“More than anything else, I’m driven by the image on the screen,” reveals Twilight supervising sound editor Gaeta. “I don’t usually work on this type of film. It has a lot of effects-heavy sequences, characters who move very fast and action sequences. The baseball game is a very concentrated loud sequence with lots of effects. It’s very thunderous. If you listen to my other films they’re the opposite––very finessed type of tracks with dialogue being prominent.”

“Thirteen was one of my first films when I started just supervising,” Gaeta says. “It came out of desperation. I was at Sound Deluxe. There were no guarantees of work for me as a sound editor. They’d been bought by Ascent Media and grown tremendously. I realized I was low on the totem pole and wouldn’t be an on-staff editor. I made a couple calls. A post supervisor gave me the film. I made the deal and that was the beginning of my company, Sound for Film.”

At Sound for Film, Gaeta works collaboratively across the Internet. “I don’t have a traditional facility; I work out of my home––most of my editors do, too,” he explains. “I use Apple iDisk. It enables us to communicate and send files back and forth through iChat. We have 10 or 20 gigabytes of space, not a lot. The really big files, like picture and OMF, are sent through a runner.”

Gaeta is a self-confessed fan of Macintosh products. “I’m running ProTools 7.3 with G5 desktop Macs,” he says. “I remember when I was made fun of because I was using a consumer editing system to cut my effects. People couldn’t believe that anyone would take ProTools seriously. On my first gig in 1993, When the Bough Breaks, one of the other editors came into my room and said, ‘You’ve got to see this; you can actually see and cut the waveform, and it’s a non-destructive edit.’ It was a two-track system called Sound Designer, the precursor to ProTools.”

“Shortening is always a huge challenge, I think my first cut on Twilight was two hours and 22 minutes. Catherine [Hardwicke] likes to be ruthless right away. Our goal was to get it under two hours.” – Nancy Richardson, A.C.E.

Gaeta will be doing the mix on Twilight as well, at Wildfire Studios. “Mixing is a new direction that I’m heading in,” he says. He’ll be mixing the HBO film Dog Year later in the year.

The Avids and the Assistants

“I first started cutting on film,” reveals Richardson. “Then I learned Lightworks, and then the Avid. I’ve been on Avid ever since. On Twilight, we’re on Adrenaline with a pretty standard workflow. We’re telecine-ing to high definition and then doing a down-convert to standard-definition DVCAM tape. I want this to be the last project that I do in standard def. I really wish, in retrospect, that I had been able to cut this in high def––because there are things you just don’t see in standard def.”

“We’re on Avid Adreneline 2.8.3,” says co-first assistant editor Alan Z. McCurdy. “We have four Avids connected by Unity. For a month or so, we added an Avid Nitris DX so we could have screenings in high definition.” McCurdy started as second assistant on Twilight after the editorial crew returned from Portland. “I’d worked with first assistant Kindra Marra on Pirates of the Caribbean 2 and 3,” says McCurdy. He became first assistant when Marra temporarily left the film.

“Assistant editors keep it organized,” says Marra. “When are the new dailies coming in? Which scenes are complete and which ones are not?” Los Angeles would ship to Portland a portable hard drive that had the dailies and media files ready for import into the Avid, as well as the back-up DVCAM tape. In Portland, visual effects editor Lara Ramirez helped keep up with the dailies.

Like the Undead that it depicts, the vampire movie never really expires––or even goes away. It just keeps resurrecting itself in new stories for another generation.

Marra joined Twilight after a friend working on another Summit film recommended her to Richardson. She was in Portland during the film’s production. “You always have your challenges when you’re on location,” she says. “Weather…getting sound back and forth… You have this two- or three-day delay by the time they process the film, get it telecined and get it back.”

The Future of Sound and Picture Editing

“This is really an evolving industry,” says Gaeta. “The lines between editorial and mixing are getting blurred. You see that happening all over town. The technology allows it to happen now.” Indeed, more can be done at a small office, without a traditional studio, than ever before.

“It’s a really strange time in Hollywood between all the strikes and the economy in general,” adds Richardson. “I think we’re heading into the way popular culture was in the 1930s during the Depression. I think musicals are going to be huge. People don’t want to see anything depressing anymore; they want to go to escape.”

by Dan Ochiva • portraits by John Clifford

“Down with kitchen sink dramas! Film us in unexpected ways just as we are!”

– Dziga Vertov

Cinema, still a relatively new art form, seems to need––even desire––a good fight over its central tenets on a regular basis. Back in the 1920s, Soviet experimentalist Dziga Vertov was already calling for a radical new cinema unlike Hollywood, followed by other manifesto wavers ranging from the nouvelle vague of Jean Luc Godard, François Truffaut et. al., and their documentary compatriots in the US (Robert Drew’s ‘Direct Cinema’ advocates the Maysles brothers, DA Pennebaker and Ricky Leacock) to the most recent proclamations by Danish filmmakers Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg, of Dogme 95 (their “rejection…of a concept of film as a work of illusion”).

All such revolutionaries proclaim a return to a basic cinema language, unencumbered by an overreliance on elaborate, post-produced effects that distance both makers and viewers from a “true” cinematic experience.

“Sound must never be produced apart from the images or vice versa. Music must not be used unless it occurs within the scene being filmed, i.e., diegetic.”

– Dogme 95

So what does all this have to do with making a film in 2008? Only that director Jonathan Demme put his talented sound design and editing crew up to a similar Dogme 95-style challenge for his latest feature, Rachel Getting Married. The romantic comedy, selected for this year’s Toronto and Venice Film Festivals and opening October 3, features actors including Anne Hathaway and Debra Winger even while offering this idiosyncratic director’s own Dogme-like approach.

Suzana Peric.

“The Dogme manifesto was quite influential in Jonathan’s thinking about how to approach the film, for the sound, visuals, and acting,” says sound effects editor Blake Leyh. In Rachel Getting Married, a varied collection of musicians––friends and partners of the groom and his producer father––are preparing music for the aforesaid wedding ceremony and party. Together, they create a constant musical commentary heard throughout the film, whether on screen or off.

That might not seem at first like such a big deal, but with musician/actors strewn throughout the sprawling Connecticut house where 70 percent of the film’s action takes place, preparing and editing the audio, and then pulling everything together in a final series of mixes became a rigorous challenge to the sound crew.

Organizational Challenges

“The biggest challenge was organization,” admits Suzana Peric, music designer and music editor on the film. “After shooting wrapped, I was presented with a folder notating the 39 hours of music recorded on the set!” Every scene had music, either seen in the shot or heard off screen. While the Dogme group’s “Ten Commandments” could seem strict––though in a tongue-in-cheek way––”What we took from Dogme was very loose,” says Peric. Demme wanted lots of options, she reveals, yet each time the musicians performed, it needed to feel unrehearsed and of the moment. Even “guests” attending the wedding were actual musicians chosen by Demme. “He is well known for using a wide tapestry of music,” says Peric.

Handling such complexity required a more open, flexible working style made in part by planning and careful pre-mixing, as well as hopping on to new trends in post-mixing. But planning can only help so much––especially in a film that had to feel loose and unrehearsed, yet was helmed by a music-savvy director who wanted to capture every improvisation. That led to mad dashes by the boom man around the set with very little chance to do standard slating. Since the movie was recording to high-definition tape systems, the camera was often kept rolling.

Tony Volante.

“Supervising dialogue editor/ADR editor Nick Renbeck and I started to hear reports back from the shooting, and we were just terrified,” says Paul Urmson, supervising sound editor/re-recording mixer. While Urmson had heard of the basic plans for shooting the summer before, he soon learned that Demme had taken to rolling through complete rehearsal dinner scenes for 30 minutes or more without stopping. Added challenges from such unfettered scenes came to the sound department as well as the film’s picture editor Tim Squyres, A.C.E.; both had to contend with wild footage taken by “wedding guests” supplied with prosumer camcorders with the charge from Demme to shoot whatever they liked.

“Sometimes there were slates and sometimes there weren’t any,” says Urmson. “Thankfully our first assistant sound editor, Igor Nicolic, did a great job taking all of the material from the picture department that had been shot, and organizing the material so that we could actually find the things that Jonathan was looking for.”