by Ray Zone

With the inauguration of television after World War II, motion picture attendance suffered a precipitous decline. From 1946 to 1952, attendance at movie theatres had dropped by almost half, from 83 million to 46 million per week. Thousands of movie theatres had closed and the motion picture industry desperately needed a way to pull the public away from their new television sets and back into theatres.

On May 6, 1948, the FCC (Federal Communications Commission), after granting licenses for a hundred TV stations, had imposed a freeze so that interference problems could be analyzed. From 1948 to 1952, New York and Los Angeles each had seven TV stations, but there were many major cities in the United States without television. This was also the beginning of commercial television with sponsored programming.

By 1953, TV stations grew exponentially, as did sales of televisions. Ray Zone Collection

The cities with television provided an excellent means of examining the impact of TV on motion picture attendance. In 1951, the cities that had television experienced a 20 to 40 percent drop in movie attendance. The cities without television reported no drop in attendance or even increased movie patronage. Locations that had television reported movie theatres closing in a great wave, including 70 in eastern Pennsylvania, 134 in Southern California, 61 in Massachusetts, 64 in Chicago and 55 in New York City.

By 1946, there had been roughly one million television sets in the United States. In his book, Here is Television (1946), Thomas Hutchinson observed that the movie studios were initially reluctant to release “any great portion of their product for television. There are several reasons why they should not,” wrote Hutchinson. “One is the fear on the part of the exhibitor as to what television programs in the home will do to his business. Just as some theatre operators believed that radio would put them out of business, the bugaboo of television drives film exhibitors to a state bordering on panic.”

By 1952, with the FCC freeze still in effect, 64 cities were broadcasting television to 15 million TV sets. On April 11, 1952, the FCC discontinued the TV license freeze and officially began processing of channel applications. The FCC approved construction of 2,053 TV facilities in 1,291 communities across the United States and, by the end of 1952, 169 new commercial TV stations had won FCC sanctions.

As of June 1, 1953, when the Hollywood 3D boom was beginning to gather a head of steam, there were an estimated 24,292,600 homes in the United States with television. For the first six months of 1953, the Radio-Television Manufacturers Association reported production of a record number of 3,834,236 TV sets. Total reported broadcast revenues for the TV industries in 1952 had been $324,200,000, a 38 percent increase over revenues for 1951. And by this time, a total of 79 percent of the United States’ population lived in an area where TV broadcast services were available.

Sound mixing session for Oklahoma! (1955) in CinemaScope. AMPAS

Despite the explosive growth of television at this time, it was obvious that the quality of the visual experience with TV could not compare to that of the motion picture. “Television programs cannot for years to come, if ever, hope to compete with motion picture theatres from a production point of view,” wrote Hutchinson. “Television program builders will never have the money to spend that Hollywood producers have, nor will they have the facilities.”

Showing 3D movies at commercial cinemas further underscored the qualitative difference between what was possible in the motion picture theatre and with TV at home. “As to the aesthetic quality in the optical image, television assuredly gives the movies, as yet, no competition at all,” wrote Parker Tyler in an article titled “Dawn of the 3Ds.” “What the 3Ds in the theatre will compete with, therefore, is the feeling via television of getting something for nothing rather than with any actually optical pleasure from television; and also, perhaps, with the charm of the lazy option of turning a dial on a passing impulse.”

Color came to television and to the movies, on a widespread basis, at about the same time. Throughout the 1940s, there was a TV “color war” between CBS (Columbia Broadcasting System) and RCA (Radio Corporation of America), whose color format eventually won out and whose fate was tied to NBC (National Broadcasting Company) and its famous Peacock in color.

On June 24, 1951, RCA had televised a one-hour color premiere of Toast of the Town (soon to be The Ed Sullivan Show), but only about two dozen TV sets in the United States could pick it up. By the end of June, RCA demonstrated its new electronic color system, and in December 1953, the FCC officially authorized NTSC color, based on the standardized RCA system, for commercial broadcasting. After spending about $130 million in development, it wasn’t until 1960 that RCA recorded its first profit from color TV. By 1965, RCA profits from color TV surpassed $100 million.

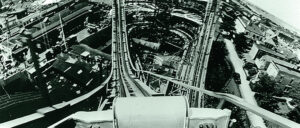

The concave screen of Cinerama in 1952. Bison Archives

THE MOTION PICTURE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK

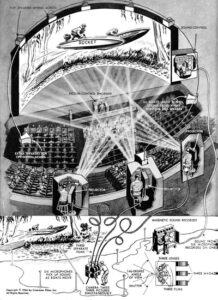

Widescreen and large-format cinema traces back to the very beginnings of motion picture exhibition. But, on September 30, 1952, when This is Cinerama, a widescreen three-panel motion picture presentation, opened at the Broadway Theatre in New York, a sensation was created. Shot with three separate strips of film running synchronized through a single-body camera and projected with three separate projectors on a steeply curved screen, Cinerama covered a field of view that was 146 degrees wide.

Cinerama was the invention of Fred Waller, who had long been working to invent widescreen cinema applications. This Is Cinerama was projected in a double system with six- track stereophonic sound developed by Hazard E. Reeves. For a petroleum industry exhibit at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, Waller had invented Vitarama, an 11-projector presentation that used a huge curved screen. During World War II, Waller had developed the Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer, an Air Force training device for gunners that consisted of five 35mm projectors, and a spherically curved screen with a field of view covering 150 degrees in width and 75 degrees in height.

With Cinerama, the screen consisted of 1,100 slats like Venetian blinds, and it reflected light directly back to the audience despite its steeply curved surface. The 35mm film in each of the camera and projector magazines was advanced six perforations at a time (26 frames per second) instead of the conventional four (24 fps). The Cinerama camera used three 27mm lenses set at an angle of 48 degrees, and the three interlocked projectors each held an oversized reel of film 7,500 feet long, for a running time of 50 minutes. The convex screen at the Broadway Theatre measured 51 feet from end to end and was 25 feet high.

A scene from This Is Cinerama!

This Is Cinerama was produced by Hollywood veteran Merian C. Cooper and featured globetrotting news reporter Lowell Thomas introducing the film. When audiences experienced a roller coaster ride on the Atom Smasher at the Rockaways’ Playland amusement park in New York on the three-panel screen, there were screams in the audience. A visit to La Scala Opera House in Italy, a trip to a Florida ski resort and an exciting aerial sequence as a finale thrilled audiences of the day with deeply immersive images.

Produced at a cost of $1 million, This Is Cinerama ran 122 weeks, earning $4.7 million in its initial New York run alone and eventually grossed over $32 million. It was obvious to Hollywood that the public was ready for a new form of motion picture entertainment. The first five Cinerama feature-length travelogues, though they only played in 22 theatres, pulled in a combined gross of $82 million. The rollout of Cinerama was slow. Costing about $90,000, retrofitting a theatre to use the deeply curved Cinerama screen and three projectors was expensive.

Opening just two months before Bwana Devil, which premiered on November 27, 1952 and launched the 3D boom in Hollywood, This Is Cinerama made going to the movies an event. Along with 3D, the widescreen entertainment model proved to be an important differentiation from the television experience at home.

The success of Cinerama made the old 1.33 to 1 aspect ratio of Hollywood films obsolete. In December 1952, 20th Century-Fox President Spyros Skouras licensed Henri Chretien’s anamorphic Hypergonar lens for use in a widescreen format that, with some modification by Fox engineer Earl Sponable, became known as CinemaScope, the “poor man’s Cinerama.” With CinemaScope, a single 35mm camera and projector sufficed to throw a panorama-shaped image 2.55 to 1 upon the screen. Fox immediately went into production on February 24, 1953 with its first CinemaScope release, The Robe, starring Richard Burton.

Though characterized by Life magazine as

a “cheap and preposterous film,” Bwana Devil launched the 3D boom of Hollywood in November 1952. United Artist

THE YEAR OF 3D

As 1953, the year of 3D, commenced, Cinerama, 3D and CinemaScope were all mixed up in the public imagination as well as the motion picture industry. The “new production and exhibition processes, including Cinerama and CinemaScope, were generically referred to within the industry as ‘3D,’” observed John Belton in his book Widescreen Cinema (1992). “However, many of these new ‘3D’ systems, such as Cinerama and CinemaScope, were merely widescreen processes and did not rely upon ‘true’ (binocular) stereo photography.” When The Robe opened on September 16, 1953, it became one of the top box-office hits of the year.

It was considerably cheaper than Cinerama to convert a movie theatre for CinemaScope exhibition. Fox estimated a conversion cost of $10,000 to $12,000 for smaller theaters and initially sold a pair of projection lenses for $2,800 and then, by April 1954, eventually dropped the cost to as little as $1,000 a pair. To increase the luminance for CinemaScope, and for 3D, Fox marketed a highly reflective aluminized screen that it called the “Miracle Mirror” at about twice the cost of a conventional screen.

Conversion costs for 3D for theatres were somewhat less expensive than those for CinemaScope. Announced right at the outset of the Hollywood 3D movie boom, CinemaScope was promoted aggressively by Fox as a viable option to 3D. Two issues of Film Bulletin, an exhibitor’s trade publication that were published in February and March of 1953, reflected the economic turmoil in which exhibitors found themselves at this time.

All of Hollywood was abuzz at this time over 3D. Just a month prior, with a January 28 issue of The Hollywood Reporter, a front- page headline had announced “Dozen 3D Films Ready in ’53, TOA [Theatre Owners of America] Told by Major Distribs; Every Company Will Have at Least One.” Bwana Devil was still breaking box-office records and Arch Oboler, the film’s writer-director, had just completed a $500,000 distribution deal for it with United Artists. The February 23 issue of Film Bulletin had considerable information about costs for conversion to 3D for exhibitors. It was also noted that Skouros was “back from an overseas meeting with the inventor of the lens used in CinemaScope.”

Bwana Devil. United Artists

An article on House of Wax (1953) reflected the confusion between 3D and CinemaScope and, in a subhead, presciently posed the dichotomy: “CinemaScope vs. Polaroids.” At the end of the article, a 3D equipment checklist titled “Things to Check for 3D Installation” was printed and covered such elements as screens, interlock, generator, arc lamps and projectors. Exhibitors knew that within the next two months, at least three more third-dimension films would be in release along with Bwana Devil. They included House of Wax, Sangaree and Fort Ti. Columbia’s Man in the Dark (initially titled The Man Who Lived Twice), shot in just 11 days, was also fast-tracked and would open in 3D on April 8, 1953, just one day ahead of House of Wax.

The March 9, 1953 issue of Film Bulletin seemed to presciently foretell the end of the 3D boom, as it promoted the competing process. “CinemaScope,” the cover proclaimed, “What The Robe Will Look Like on the Wonder Wide-Screen. Will It Be the New Movie Miracle?”

For many decades, motion picture trade publisher James R. Cameron had produced manuals for projection professionals and theatre managers. Cameron hurriedly issued a volume on Third Dimension Movies and E-X-P-A-N-D-E-D Screen (1953), when the trend became evident. “The most important question before the industry right now is one of standardization of the new three-dimension equipment,” wrote Cameron. “What it will cost exhibitors to convert over to the new third-dimension or expanded screen cannot be approximated until such time as plans are made for the standardization of equipment, and the production costs are known.”

Warner Hollywood Cinerama Theatre in 1953. Bison Archives

As a technical professional, Cameron was very clear about the difference between 3D and widescreen. “The exhibitor will have to decide which of the two systems will be best for his theatre, either third-dimension or expanded screen,” he wrote. “The two systems are entirely different and have nothing in common.

EXHIBITOR’S CHOICE

The exhibitors were faced with a choice. Cameron was also very clear about ongoing additional costs of exhibiting 3D movies. “An important point to take into consideration is the fact that all of the projection equipment was originally designed and constructed to take care of intermittent projection, a 20-minute period of operation and then a 20-minute period of rest,” he cautioned. “With three dimension projection, the equipment will be

in continuous operation, and it is possible that the equipment will not stand up under this usage.” So, twice the amperage was necessary to project 3D and, given the unionization of the industry, an additional projectionist was also generally considered necessary. In the case of Cinerama, six projectionists, sometimes eight, were required for a single showing.

Also in that March 9, 1953 issue of Film Bulletin that seemed to predict the demise of 3D, under the Exhibitor’s Forum, an item titled “Caution on 3D” from the Allied Caravan chain of theatres advised that “prudent small towners had better bide their time carefully so as not to have expensive equipment become obsolete when and if standardization is accomplished.”

So, early in 1953, exhibitors were faced with a number of options for refashioning their exhibition models — all of which meant spending money. Box-office attendance still continued to drop. By March 1953, a considerable number of 3D releases had been announced but Fox was beginning to promote CinemaScope, and the box-office windfall that The Robe seemed to promise for exhibitors.

Fred Waller’s Cinerama used three separate strips of film running on three synchronized projectors and a steeply curved screen covering a 146-degree field of view. Ray Zone Collection

A cover story in the December 1953 issue of American Cinematographer posed the question: “Is 3D Dead?” The editors who created the survey provided a forensic report on the 3D boom. “So what is the picture today?” the editors asked. “Exhibitor feeling toward 3D is varied and seldom enthusiastic. And when exhibitors are reluctant to buy, the studios are naturally reluctant to make 3D films.”

R.M. Hayes, in his book 3D Movies, A History and Filmography of Stereoscopic Cinema (1989), enumerated some of the 3D business practices that led to exhibitor disenchantment with stereo films. Hayes noted, “Cropped widescreen, increased use of color, CinemaScope, stereophonic sound and, of course, 3D had all been embraced as weapons against the ultimate intruder, television. All these cost millions of dollars to develop and provide, and the studios naturally passed this on to the exhibitors. To install new screens, lenses and sound systems ran each theatre many thousands of dollars.”

Hal Morgan and Dan Symmes, in their book Amazing 3D (1982), also noted that 3D had been “stifled by greedy distributors who antagonized exhibitors with unfair financial terms.” Even though 35mm single-strip solutions had been developed by this time to cut down costs for production and exhibition of 3D movies, the exhibitors had made their decision.

In 1953, there had been 200 to 250 exhibitor requests per week to Fox for CinemaScope installations. By April 1954, there were approximately 3,500 theatres with CinemaScope screens. A year later, that number had grown to 13,500. Widescreen had won the format wars. Film historians now call the period between 1954 and 1956 the “CinemaScope Rebound” after the challenge that television presented to the motion picture industry.