by Laura Almo

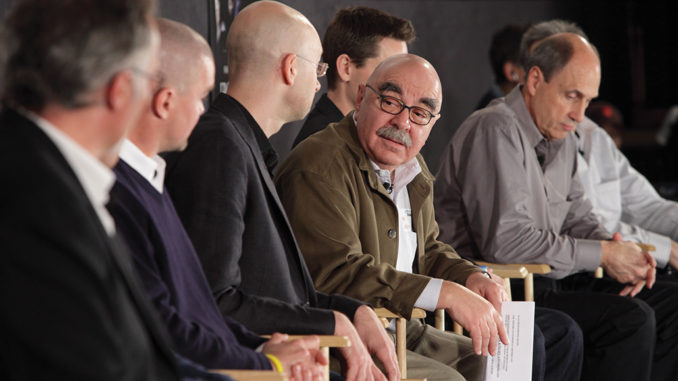

Amid the pre-Oscar festivities, the American Cinema Editors (ACE) held its ninth annual Invisible Art/Visible Artists Seminar with the Academy Award-nominated picture editors at the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood. Moderated by Alan Heim, A.C.E., the seminar featured insightful conversation about their nominated films and their approach to editing.

The panel included Lee Smith, A.C.E. (The Dark Knight); Mike Hill, A.C.E., and Dan Hanley, A.C.E. (Frost/Nixon); Elliot Graham (Milk); Kirk Baxter and Angus Wall (The Curious Case of Benjamin Button); and the ultimate winner, Chris Dickens (Slumdog Millionaire).

Alan Heim: Lee, the clip you selected from The Dark Knight is an action sequence with very little music. Talk about editing this action sequence.

Lee Smith: It was a lot of fun to cut and also very bold because, traditionally, you would run music the whole way in a sequence like that. We wanted to go with straight sound. It was amazing.

The interesting thing with Chris Nolan, the director, is that his idea is never to cut with music––to force you to be selective and to make all of the hard decisions. And then make music the icing on the cake. For other directors in years gone by, I’d put music in because it makes me look good. Every time I’d run it for a director, I’d sit back and go, “What do you think?” and they’d say, “That’s fantastic.” But it was actually crap. I just smoothed it over with the music and nobody knew.

But when you cut without music, it really hones your skills. In fact, we presented the entire first cut without a single frame of music and it was terrifying. When Chris looked at the car chase, he decided we should go with very little music. When you see it in context, I think it works even better.

AH: I find it refreshing that when the music came in, it had so much more power.

LS: Being an old sound guy, I really go to town on the Avid. We were always running with very strong sound. We were fortunate enough to have a great location sound recorder. I always had a lot of sound to cut with, and there were a lot of visual effects.

AH: Mike and Dan, you have been working together for 27 years for Ron Howard; do you guys work on alternate scenes?

Mike Hall: Yeah. We don’t work together. Really, we don’t see each other much. Whoever takes the first scene that comes in, the other guy takes the next one. Every once in a while, there might be a scene that one of us wants to do in particular and we’ll say, “Do you mind if I do that one?” We flip a coin sometimes too on the really good scenes.

AH: When Ron comes into the cutting room, do you work together?

Dan Hanley: We get all of his notes and then he’ll bounce back and forth between rooms and intercut stuff that we’ve cut. Mike will re-edit or come up with an idea, or vice versa. I think there is a benefit to being able to bounce ideas off other people and having one be another editor, because he can kind of understand what you had in mind, possibly, when you first put it together. He’ll look at the dailies and he might have another idea that you just didn’t think of.

AH: Kirk and Angus, can you talk about how you structure a scene in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button?

Kirk Baxter: I treat it in isolation, as if it is the only scene that exists––and make sure it works perfectly in isolation. Then I put in what surrounds it, and say, “Oh, that doesn’t work anymore.” Then I have to do it again and again and again. It’s an exercise in patience; I love the passing back and forth. Not every editor works that way, but with Angus and me, we can reach a point where we think it’s done and then someone else has a little piddle with it.

Angus Wall: There are tent poles in a scene, like there may be a performance you have a visceral response to; something that happens that really may ring true. There are these little magic moments that make you say, “That’s got to be in the movie”––even though you may end up abandoning them. You stake those out and try to figure how to get from this one to that one. It’s a dance between these little moments and the overall structure of the scene––how things are blocked, whether you need a close-up or a master––that’s the pull back and forth between structure and performance.

AH: Elliot, Milk has a great deal of documentary footage; how did you do it?

Alan Heim moderated the panel of the Oscar-nominated editors. Photo by Gregory Schwartz

Elliot Graham: Well, the documentary footage component didn’t come in too much until post-production. We had the idea to use a little bit. Director Gus Van Sant had assembled about 100 hours of stock footage just to prepare himself to shoot the film, to immerse himself in the year and the place to influence his filmmaking. Gus had the idea that maybe there was some way to use the stock footage. I tossed it in in a few places, and we were really, really liking it; it gave a real sense of place to the Castro and San Francisco that we didn’t have otherwise.

Then, in post-production, we realized there were some story points and a greater sense of place that just weren’t coming across, and we didn’t have $200 million to go re-shoot. But we did have 100 hours of footage that we can use if it will work. We just started sifting through the stock footage, and everything that could augment anything that we felt needed a little bit more storytelling we would toss in––and we found it really did work.

It was a joy to have stock footage because it allowed us to solve problems in a really unique way that I think helped elevate the film.

AH: Chris, you’ve been in situations with a lot of documentary footage; your film Slumdog Millionaire looks like documentary footage. Talk about that.

Chris Dickens: The director, Danny Boyle, shot it a little bit like a documentary at times: hand-held, and a lot of extra things––and so you have a lot of choices. Also, the style needed to feel real and scenes needed to feel distinct. So we have the TV game show, we have some mundane reality with the lead character, and of course we have to go back in time for it to feel more organic.

AH: The length of a movie is like a piece of string; a movie should be whatever length the story calls for. The critics have talked about the excessive length of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. Let’s say if there’s a fault to be had in the length of a movie, it’s the director’s fault, of course. But at two hours 45 minutes, the film is pretty long.

KB: I take pride that we supported the movie that director David Fincher wanted to make. We had things up our sleeves if orders were to come down to make it shorter. The way the script was written, so many things were set up and they paid off later. There are so many scenes and they are all quite lean so you end up losing a lot to gain little in time. David made the decision to remove time but not content, so our job became to make everything as tight as we possibly could without breaking it.

AW: Ironically, sometimes it can make the film feel longer if things are faster. It’s a very delicate balance there, and sometimes if a scene is allowed to breathe a little bit, it actually plays a little quicker.

LS: With The Dark Knight, we just didn’t ever measure the movie in time, for any reason. You just keep going and, because of the script, what happens is that you tend to arrive at a certain length. I think the length of the movie is what it is. Once you know you’ve hit the sweet spot, everyone isn’t telling you it’s too long. I’ve worked on films cut too tight; a film can be completely ruined by just mercilessly cutting it to some perceived length.

AH: Chris, the look of Slumdog Millionaire is absolutely spectacular and the style of the editing is just wonderful. What would you like to say about it?

CD: Well, it was a kind of tricky film to cut because we had an embarrassment of riches, really; too much good stuff. I loved every moment of it and therefore the first cut was very long. We struggled to make it work cohesively. That was the biggest challenge. We had to condense the film, but also get more in it. We tried to overlap the stories and, rather than cut from one story to another, we tried to make it feel like one story. So you are unaware of being taken from one to another.

Questions from the Audience:

Question 1: What was the most memorable day you experienced while editing this film?

MH: It’s always memorable when you finish the film and you see it in its final form; it’s a very gratifying experience.

EG: The premiere of Milk at the Castro Theatre in San Francisco, which was featured throughout the film, is an iconic landmark throughout the Castro. We were surrounded by many of the gay men and women who had lived there for decades and had been there during Harvey Milk’s time. They were a huge part of the audience at the premiere, so to be sitting in the Castro Theatre, watching that theatre on screen with an audience of people who had actually gone through the experiences being presented, was incredibly special and unique. It certainly emotionally affected a lot of them––and therefore us.

Question 2: What scene in your film was most reworked or changed from first edit to final cut?

LS: The sequence where the Joker plants some bombs on the Gotham City ferries and they have the SWAT team go into a skyscraper. It was just an unwieldy beast. They shot 22,000 feet of crowd reactions on one day––it nearly killed me! I just kept cutting it and cutting it, it was really hard to get it to make sense. It had very complicated visual effects that were key to your understanding of where you are within the building. It was a scene that just went on and on.

Thank God we were working on non-linear editing devices! I used to cut on film and I have no understanding of how we would have arrived at what we got on film because I needed 10 or 12 versions to keep referring to––just to find out which one actually was better.

Laura Almo is a freelance writer and documentary filmmaker, as well as an editing teacher. She can be reached at lauraalmo@mac.com.

Comments are closed.