by Edward Landler

From the age of six, Ada McGrath refuses to speak, yet film audiences first saw and heard how clearly she communicates on May 15, 1993, when Jane Campion’s The Piano premiered at the 45th Cannes International Film Festival. At the festival’s awards ceremony on May 24, its star, Holly Hunter, was named Best Actress for her portrayal of this mute woman who expresses herself through a combination of self-invented sign language, her eyes, and the exquisite music she creates on her piano.

Also at the close of the festival 25 years ago, writer/director Campion became the first — and still the only — woman director whose film received Cannes’ highest honor, the Palme d’Or (shared with Farewell My Concubine by Chinese director Chen Kaige), for this Australian production shot entirely in New Zealand. Setting the film in her native land in the mid-19th century, yet speaking to the present, the filmmaker captured in Hunter’s Ada a deeply elemental drive for female integrity in a male-dominated society.

Campion had begun writing the screenplay, originally titledThe Piano Lesson, in 1984. In a May 1993 interview with Miro Bilbrough for the Australian film journal Cinema Papers, she said she was inspired by the all-consuming romance of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, Emily Dickinson’s poetry and antique photos of New Zealand’s Maori people, “sitting with great dignity…their sense of themselves was so powerful.”

Re-imagining the land’s British settlers and using the piano “as the central mechanism from which the story evolves” allowed her to write, Campion said, “about characters who don’t have a 20th century sensibility about sex… We grow up with so many expectations around it that it’s almost like the pure erotic sexual impulse is lost to us. But, for them, the impact of sex is not softened.”

In 1987, Campion showed her first draft to producer Jan Chapman who stated, as print ads later proclaimed when the film was released in the US, “I was determined to finance The Piano in such a way that Jane’s original vision could be retained.”

After Campion received acclaim for her first two features, Sweetie (1989) and An Angel at My Table(1990), the Australian Film Commission and the New South Wales Film and TV Office jointly invested $85,000 seed money in the project. This helped Chapman attract the attention of the recently founded French production company CIBY 2000.

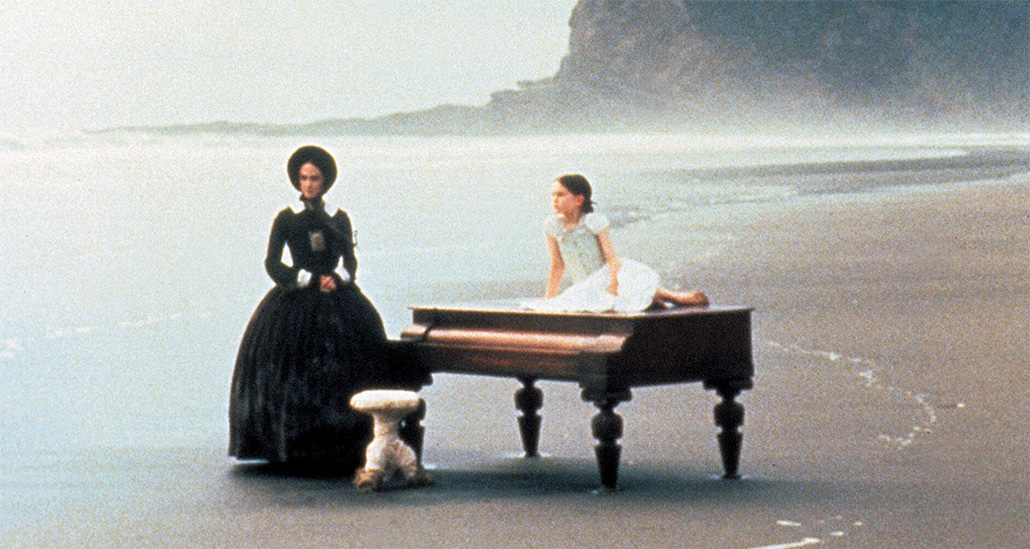

The Piano.

Miramax/Photofest

CIBY was then producing David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992), the theatrical prequel to his TV series Twin Peaks(1990-91). Campion completed the shooting script of The Piano late in 1990 and CIBY agreed to provide the $7 million budget for the picture.

Among the actors Campion considered for the mute pianist Ada were Isabelle Huppert, Anjelica Huston, Sigourney Weaver and Juliette Binoche, but Hunter fought for the role. In a fall 1993 article in Filmmaker magazine, she declared, “I read so many scripts where there’s this effort to make a feminist story [but] the women are written like men. I thought Jane was really captivated by the notion of her femaleness. Ada was the perfect palette. It was all the stuff I had not explored before.”

An accomplished pianist, Hunter had learned the instrument during her childhood and into late adolescence. Campion had doubts, however, about the actress’ small stature. She told Cinema Papers’ Bilbrough she had wanted Ada “to be a tall woman with a strong, dark, eerie Frida Kahlo-sort of beauty. But, in Holly’s audition tape, her gaze was stupendous.”

For the music that expresses the emotional core of the movie — both the incidental music and the music that “speaks” for Ada through her piano playing — composer Michael Nyman based his score on Scottish folk and popular songs since Ada was from Scotland. It was, he noted to Bilbrough, “as though I was writing the music of a composer who happened to live in Scotland, then New Zealand, in the mid-1850s.”

Nyman also revealed to Varietyin November 1993 that Hunter found the pieces he wrote for her to perform on screen “so childishly simple that it gave me the chance to write stuff that was more challenging… Not only did she cope technically with everything I threw at her, but she put emotion in the music and made it very, very personal.”

In open auditions with 5,000 other young contenders, nine-year-old Anna Paquin read for the role of Flora, the daughter Ada brings with her half way around the world to New Zealand. “It was remarkable to see someone so young with such an instinct for performance,” said Campion. During production, Paquin and Hunter developed such a mirror-like closeness, the filmmaker observed, “Anna would use all Holly’s mannerisms of performance.”

In preparing for her role, Hunter worked with Darlene Allen (who taught Lily Tomlin American Sign Language for Nashville, 1975) to create an original sign language for Ada that could only be understood by Ada and Flora. Hunter herself taught Paquin this sign language, bringing the two closer together.

From early on, Campion had envisioned Sam Neill as the farmer Stewart, who arranges with Ada’s family to ship her to New Zealand to be his wife. To play Baines, the settler who has taken on Maori ways and is attracted to Ada, the filmmaker sought out Harvey Keitel for his “concentration, masculinity and gentleness.”

Another major character and dominant presence throughout the picture was the landscape of New Zealand itself. The mountainous ocean waves, the dense green bush rising out of thick mud, and the lush craggy hillsides all exist intimately in proximity to the human characters.

The Piano.

Miramax/Photofest

Campion started consulting with production designer Andrew McAlpine back in 1989 to determine the physical atmosphere of the film. Together they scouted locations for two months during pre-production. For the black sand beach upon which Ada’s piano is stranded early in the film, McAlpine told Variety that they chose “one of the favorite beaches of my childhood,” just 45 minutes from Auckland.

During production, the designer had his crew alter every landscape to enhance its feeling or mood. For the land surrounding Stewart’s house, he “transplanted and charred dead trees to create the illusion of a muddy five acres of primary slash burn,” he said in the January 1994 TCI: The Business of Entertainment Technology and Design magazine. “We didn’t want to slavishly re-create some imagined reality, which is so often seen in period films… What I wanted to do was a film in mud and charcoal.”

To enhance period realism, McAlpine found furniture, fabrics and hand props in London markets and Australian auctions. Campion had envisioned an upright piano for the movie’s star prop, but after she learned that uprights did not exist until about 10 years after the film’s action, McAlpine found an 1835 grand piano in London for her. Hunter played this authentic original in scenes set in interiors, and replicas were built and used for location scenes and Foley work.

The 12-week shoot ran from February into mid-May 1992 with director of photography Stuart Dryburgh, who had also shot Campion’s An Angel at My Table and, later, her adaptation of Portrait of a Lady (1996). To evoke the period, he said in Cinema Papers,“We used a 19th century stills process — the autochrome — as an inspiration. That’s why we tended to use strong color accents… the blue-green of the bush, amber-rich mud. ‘Bottom of the fish tank’ was the description we used to help define what we were looking for…working with natural light whenever possible.”

Another significant influence during production was the presence of Maori advisors helping the filmmaker with the indigenous characters’ dialogue and interactions with the settlers. Campion affirmed, “The cross-cultural quality of it was one of the deeply moving aspects of being on the production for all of us, cast and crew.”

After two weeks on location, the shoot continued on sets that McAlpine had built in Auckland, with the house sets surrounded by cycloramas and tree trunks brought from their exterior locations.

For three weeks just prior to production, Campion worked with Hunter and Keitel in an old wooden church in Auckland for six hours a day to rehearse their intimate scenes together. Almost three months later, during the last three weeks of the shoot, all of their interior scenes were shot in sequence.

The director had wanted the actors to help her determine the specific actions of their erotic scenes, but it did not work out that way. As Campion told Cinema Papers’ Bilbrough, “Holly and Harvey said, ‘Whatever you wanna [sic] do, we’ll try.’ They said it was too intimate, that I had to decide what would happen.” One thing the director wanted to happen was full frontal nudity — not to be displayed by Hunter but by Keitel, who willingly complied.

Re-imagining the land’s British settlers and using the piano “as the central mechanism from which the story evolves” allowed her to write, Campion said, “about characters who don’t have a 20th century sensibility about sex…”

Another aspect of Campion’s directing style was disclosed by Claire Corbett in an essay drawn from her diary that appeared in the 1999 book, Piano Lessons: Approaches to ‘The Piano.’Second assistant editor on both The Piano and Sweetie, Corbett describes photos in the editing room of actors and crew members, both male and female, wearing dresses on set, remarking, “Jane always has a dress day at least once during her shoots; all cast and crew have to wear dresses… Jane says she feels much closer to her male crew members once she’s seen them in a dress.”

Corbett started work in the movie’s Sydney editing facility during the first month of a four-month fine cut process. Working with editor Veronika Jenet, who has edited five of Campion’s films, she thought the two-and-a-half-hour first cut of the film was “already powerful.” Corbett added, “We were especially lucky to have Michael Nyman’s music flowing through the cutting rooms for hours every day.”

Joining the post-production team as sound designer was this year’s picture editing Oscar winner for Dunkirk(2017), Lee Smith, ACE, who told CineMontage, “I was doing quite a bit of sound design at that time. In Australia, as sound designer I’m in charge of everything other than the music — the same job as sound supervisor but creating sound as well as supervising.” Campion asked him to join her film after seeing (and hearing) his work in Phillip Noyce’s Dead Calm (1989); he later was sound designer for two more of her films.

Exploring the full range of New Zealand’s natural sounds, Smith contacted a wildlife expert with a large collection of recordings of native birds and animals. “We even used sounds of wildlife that no longer exist,” he explained. These and sounds of the natural elements in every scene express the vivid sense of an untouched environment.

The Piano.

Miramax/Photofest

Smith also paid heed to all the intricate personal actions: Ada tapping on piano keys in close ups, Baines’ finger touching the hole in Ada’s stocking, etc. Focusing on the mute Ada, he said, “We heightened the sense of everything she could hear” and, in a violent scene, altered the acoustics of the rain to better convey her state of mind. “Campion loved all the detail that we could put into the sound,” he added. “It was one of my favorite jobs.”

After the final mix, the original title was shortened to The Piano to avoid confusion with August Wilson’s unrelated 1987 play. Bob and Harvey Weinstein’s distribution company Miramax, which bought the American rights, launched an aggressive ad campaign for its release. Despite Keitel’s nudity, the Motion Picture Association of America gave it an R rating.

The film was nominated for eight Academy Awards, with Campion the second woman ever nominated for Best Director and Jenet the first Australian in contention for Best Editor. In a disturbing irony given last year’s disclosures of Harvey Weinstein’s history of sexual assault, and the subsequent rise of the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements, Miramax proudly ballyhooed that seven of the nominations were for women, including producer Chapman for Best Picture and Janet Patterson for Best Costume Design. The eighth nominee was Dryburgh for Best Cinematography.

The film won three Oscars — Campion for Original Screenplay, Paquin for Supporting Actress and Hunter for Actress. Accepting the award, Hunter added thanks to “…Eileen Parrish, my first piano teacher, and I need to thank my parents for letting me take those lessons.”

A full synthesis of sound and imagery inseparable from Hunter’s performance, The Piano keeps on touching us beyond the screen. Its depth of feeling makes tangible the possibility of an emotional ground on which woman and man may regard one another as equals.