“…I would like to call this new age of cinema the age of caméra-stylo [camera-pen]. By it I mean that the cinema will gradually break free from the tyranny of what is visual, from the image for its own sake, from the immediate and concrete demands of the narrative, to become a means of writing just as flexible and subtle as written language…”

– Alexandre Astruc,

“The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La Caméra-Stylo”

by Edward Landler

A change in movie storytelling and editing was already under way when French film critic and soon-to-be film director Alexandre Astruc wrote these words in an article in the magazine Écran Français in 1948. The change he saw was the growing influence of the longer-take, depth- of-field photography of Jean Renoir’s films of the late 1930s edited by Marthe Huguet and Marguerite Renoir. This approach to film story enabled viewers to identify more closely with characters’ immediate feelings. It revealed more than just plot — it revealed the inner workings of emotion. The camera-pen could reveal the psychology and essence of the person.

The camera-pen and the editing of its observations — both visual and aural — elevated the personal story above the workings of plot. The incorporation of these kinds of observations lies at the heart of the changes in American movie storytelling of the late 1960s and ‘70s.

Instances of these observations existed in film before Renoir and influenced him — among them, Luis Buñuel’s L’Age d’Or (1930) and Paul Falkenberg’s picture and sound editing of Fritz Lang’s M (1930). And in 1936, the singularly named Myriam contributed the brilliantly ironic cutting that seamlessly integrated the picture, central narration and minimal dialogue of the French “memoir” film The Story of a Cheat, written and directed by (and starring) Sacha Guitry.

The Last Picture Show (1971). Columbia Pictures

In the early 1940s, as noted by Astruc, these beginnings evolved into Orson Welles’ multiple views of Citizen Kane (1941) and the opening “narratage” of The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), both edited by Robert Wise. Over the following 20 years, this influence broadened. The lineage runs through Italian neo-realist films and their outgrowth into the stylistic precision of Michelangelo Antonioni’s films edited by Eraldo Da Roma and the interior worlds created by Federico Fellini, as well as Ingmar Bergman’s films of the ‘60s and, most noticeably, the work of the French Nouvelle Vague (New Wave) directors.

The development of lightweight camera and sound equipment during World War II further affected filmmakers’ ability to record the perception of personal emotion. This advance nurtured neo-realism’s reliance on location shooting. But its mobility continued to increase over the next 15 years, making possible bursts of experimentation in style and narrative in France, Britain and Latin America.

The mobile camera and sound equipment gave film an immediacy and participatory quality to which editors quickly adapted their techniques, transforming the world of documentary filmmaking first. Free Cinema in Britain (the early work of Tony Richardson, Karel Reisz and Lindsay Anderson) emerged almost simultaneously with Robert Drew’s Direct Cinema in the United States and cinéma-vérité in France (the films of Jean Rouch and Chris Marker).

The impact of these movements’ documentary techniques on fiction filmmaking exploded in the earliest French New Wave films. François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959), edited by Marie-Josèphe Yoyotte, and Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960), edited by Cécile Decugis, radiated a vibrant spontaneity with their jump cuts and seemingly accidentally observed incidents with little hint of being staged. Their subsequent work, along with the films of Alain Resnais — like Hiroshima, Mon Amour (1959) and Last Year at Marienbad (1961), both edited by Henri Colpi — expanded the range of New Wave techniques with innovative uses of music, voiceovers and flashbacks.

The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970). Warner Bros.

British filmmakers followed suit in The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962) and Tom Jones (1963) — both directed by Richardson and edited by Antony Gibbs, A.C.E. — and Richard Lester’s less obviously scripted A Hard Day’s Night (1964), edited by John Jympson. The technical revolution also found fertile ground in Latin American countries seeking stronger cultural identities in their films — in Brazil’s Cinema Novo movement founded by directors Glauber Rocha, Nelson Pereira Dos Santos and Ruy Guerra, and in the work of Tomás Gutiérrez Alea and Humberto Solas in Cuba.

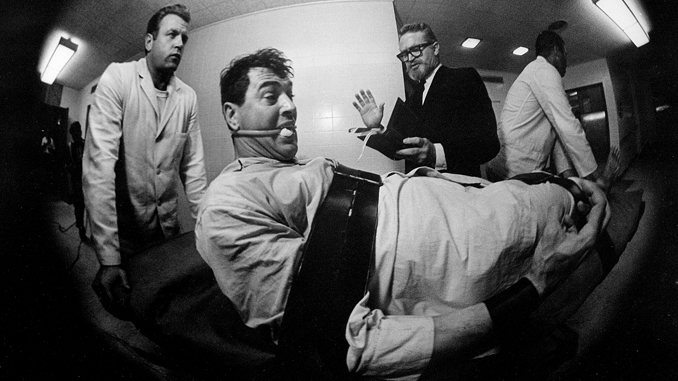

Perhaps the first inklings of the stylistic revolution in Hollywood appear in three of John Frankenheimer’s movies edited by Ferris Webster. Dramatically different from the intricately cut brainwashing scenes in The Manchurian Candidate (1963), Webster’s editing of the film’s political gatherings, including the climactic presidential convention, in the style of contemporary news documentaries, helps the audience to accept the story’s conspiratorial premise. The news-style cutting of the demonstrators outside the White House at the beginning of Seven Days in May (1964) serves the same purpose.

But Webster’s editing of Seconds (1966) utilizes jump cuts in sequences involving a middle-aged businessman played by John Randolph — walking through Grand Central Station, trying to do a crossword puzzle on a commuter train, getting a phone call in his home study — to convey the character’s profound emptiness and malaise. The jump-cutting strategy completes this personal story when, after trying a different lifestyle with a new physical identity in the form of Rock Hudson, the businessman is gagged and strapped to a hospital gurney. As a minister intones last rites over him, Howard Beals’ sound effects editing underscores the man’s terror as he is wheeled to his appropriate “disposal” in a consumer culture.

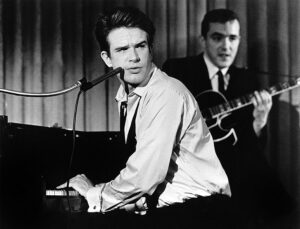

Arthur Penn’s Mickey One (1965), tracing the personal journey of a stand-up comic (Warren Beatty) on the run from the mob, may be the first American film to build most of its editing structure on New Wave techniques. An editor for TV news documentaries before moving to features, Aram Avakian demonstrates his facility in cutting location photography, creating lyrical sequences of seedy environments and compressing the action with long dissolves. During conversations, he uses jump cuts to point up subtle changes of feelings between characters. He also shares the New Wave’s playfulness with fast- and slow-motion action, as sound editors Edward Beyer and Hugh A. Robertson meld improvisations by jazz saxophonist Stan Getz over sequences without ambient sound.

Medium Cool (1969). Paramount Pictures

Four years later, a huge photograph of New Wave actor Jean-Paul Belmondo hangs over a fireplace in Medium Cool (1969), written and directed by cinematographer Haskell Wexler. Photographed by Wexler as well, the film does more than make a nod to its stylistic genesis. Verna Fields’ picture editing and Kay Rose’s sound editing make Medium Cool the first full assimilation of New Wave storytelling techniques in American film.

A car horn endlessly sounds over the first image — a rack focus shot from inside a wrecked car through its broken window — that cuts into a sequence of precisely framed jump cuts following a motorcyclist through different parts of Chicago to deliver TV news film, then into a sequence of jump cuts of conversations during a TV newsroom party, which introduces newsman Johnny Cassellis (Robert Forster). The film’s pace continues through six months of his life, leading to the bloody demonstrations at the 1968 Chicago Democratic Convention. Throughout, the technical invention never fails to stimulate and intrigue. Nor does it fail to evoke Cassellis’ growing recognition of his place in the broader social perspective.

Harkening back to Italian editor Da Roma’s cutting of Roberto Rossellini’s Open City (1945), Wexler and Fields unobtrusively intercut staged material with actual documentary footage. Borrowing from New Wave sound overlapping, Rose plays jazzy music over a roller derby match and, when a fight breaks out in the rink, cuts to raucous ambient sound which continues over jump-cut close shots of Johnny making love with his date after the match. And, over dialogue at times, the cutting directly shows what the speaker is talking or thinking about or looking at.

McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971). Warner Bros.

Innovative techniques soon come to enrich apparently conventional movie story genres in more than superficial ways. Robert Miller’s sound overlapping effects in Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969) add an ironic dimension, while editor Lou Lombardo’s intercutting of various camera speeds in action scenes contributes a real sense of human perceptual reaction to direct physical violence. In Peckinpah’s The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970), Lombardo contributes split-screen effects showing progressions of action over time. More importantly, Lombardo and sound mixer Don Rush, CAS, splice together a single seamless, continuous conversation between Jason Robards’ Cable and Stella Stevens’ Hildy played out over the course of perhaps several days.

With sound mixer Barry Jones, Lombardo further explores sound cutting and overlapping in another western, Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971). The conversation about the town’s newly arrived prostitutes among men playing poker is extended over a montage of the women — including an “authentic Chinese princess” played by future editor Maysie Hoy, A.C.E. The montage ends as the women begin singing “Beautiful Dreamer,” which carries over into the next scene. In similar sequences and in scenes of seemingly inadvertently perceived actions, and in scenes with the cutting cued to businessman gambler McCabe talking to himself, Lombardo infuses the movie with a New Wave sensibility.

By the early ‘70s, this sensibility has come to lurk under the surface of many of the era’s movies. No matter what genre, the movies become anchored to the personal story, character development and character relationships. But the New Wave elements are often mixed with other influences and grow into entirely new stylistic approaches.

Mickey One (1966). Columbia Pictures

The experimental avant-garde cinema informs Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969), edited by Donn Cambern, A.C.E., with its strategically repeated flash forwards — most strikingly intercutting the savage beating of the motorcyclists and its aftermath — and an impressionistic New Orleans drug binge. Throughout Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show (1971), though, Cambern consistently cuts from the long-take, deep-focus photography to POVs of specific characters to suggest their feelings and states of mind.

Both movies, however, under the supervision of sound editor James Nelson — with LeRoy Robbins mixing Rider’s rock song score and Tom Overton, CAS, mixing Picture Show’s Country and Western music — break significant ground with the overlay of popular songs carefully chosen to reflect the mood of specific scenes as well as the cultures of the eras depicted.

A mystery thriller on the surface, Alan Pakula’s Klute (1972), edited by Carl Lerner, combines two new styles of editing to become a study of its central characters: Jane Fonda’s call girl and Donald Sutherland’s policeman. The first, derived from Da Roma’s work with Antonioni, is a sharp-cutting style framed by the film’s architectural environments. The second, most apparent in Fonda’s scenes with her analyst, is akin to John Cassavetes’ technique in his independent films of not cutting away from the actor to reaction shots.

Similarly, Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1972) becomes more than a gangster movie with New Wave elements. Visibly evolving out of the opening vignettes introducing the main characters, the editing of Sid Levin, A.C.E., creates a style of its own, intricately interweaving the ambient sound, voiceovers and popular music arranged by sound mixer Don Johnson, CAS, and re-recording mixers Walter Goss, John Wilkinson and Bud Grenzbach. Gradually, it draws the audience in to identify specifically with the outlook of Harvey Keitel’s conflicted Charlie.

Dog Day Afternoon (1975). Warner Bros.

Having effectively used New Wave techniques in Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and Little Big Man (1970), Dede Allen, A.C.E., transforms those techniques into unique approaches to match the story structures of Serpico (1973) and Dog Day Afternoon (1975), both directed by Sidney Lumet.

With co-editor Richard Marks, A.C.E., on Serpico, she constructs the storyline through a multitude of short scenes interwoven and spread out over years by strictly adhering to the central figure’s perspective. Helping to achieve this, sound editors Edward Beyer, Richard Cirincione, Jack Fitzstephens and Robert Reitano, along with mixer James Sabat and re-recordist Dick Vorisek, draw sharp attention to what Serpico hears to drive the flow of the picture cuts. Sound details are sometimes even pre-lapped, heard in advance of their related picture.

In Dog Day Afternoon, Allen carefully balances the tensions between the tightly shot dramatic situation of robbers and hostages inside a Brooklyn bank and the documentary-style footage of the police and crowds of spectators gathered outside the bank. The interlacing of interiors and exteriors acutely observes the relationships of the individuals comprising the masses — most immediately, perhaps, when Al Pacino’s Sonny firing a shotgun inside the bank is followed by a succession of quick cuts picturing the intense human ripple effect.

Above: Annie Hall (1977). United Artists

Perhaps the major changes in American editing from the early ‘60s to the late ‘70s can be most simply summed up by two glimpses into Ralph Rosenblum’s work. In Sidney Lumet’s The Pawnbroker (1964), he paid direct homage to New Wave director Resnais’ documentary Night and Fog (1955) by introducing flash cuts of a Nazi death camp to portray the inner life of a Holocaust survivor running a pawnshop in New York.

In 1977, with Wendy Greene Bricmont, A.C.E., sound mixers Jack Higgins, James Pilcher and James Sabat, and sound editor Dan Sable, Rosenblum edited Woody Allen’s Annie Hall down to 93 minutes from a 140-minute first assembly. As he says in his book, When the Shooting Stops…the Cutting Begins, written with Robert Karen, “Out of the vast amount of material that Woody thought was going to comprise his first personal commentary film, we found a love story about two different, perhaps incompatible, people…”

Rosenblum had cut most of Allen’s previous directing efforts but, with a radical shift in storytelling and editing style, Annie Hall became the comedian’s first mature film. To make that happen, rather than the traditional Bar Mitzvah fountain pen, Rosenblum gave him a camera- pen.

And like Allen, the best American filmmakers — and the editors with whom they work in collaboration — have come to tell their stories with the camera-pen and its ever-growing palette of editing techniques, first fully displayed by the Nouvelle Vague.